While a major part of main stream media and think tanks is focused on the tip of the iceberg, SouthFront: Analysis & Intelligence provides an exclusive review of the origins of the South China Sea Crisis.

Written by Brian Kalman exclusively for SouthFront: Analysis & Intelligence. Brian Kalman is a management professional in the marine transportation industry. He was an officer in the US Navy for eleven years. He currently resides and works in the Caribbean.

A long brewing crisis of both regional and global proportions has been festering in the South China Sea in recent years between claimants to a variety of islands, reefs and shoals and more importantly access to oil and natural gas resources that are worth trillions of dollars. Although this dispute, or more accurately put, many individual and interlocking disputes, have gained in importance in recent years, they have been a bone of contention for centuries. The discovery of vast stores of oil and natural gas and the assertiveness of a resurgent China have brought a long dormant dispute back to a level of international importance.

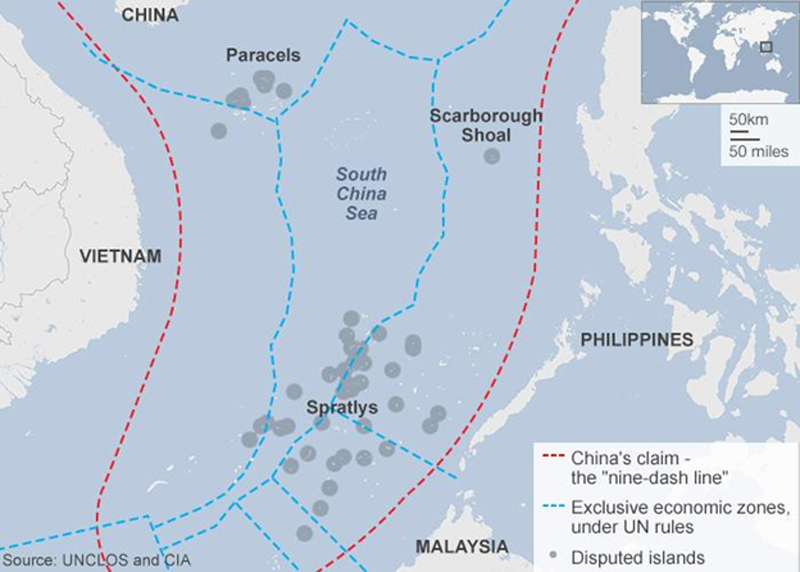

The “dispute” may be broken down into three main areas of argument. The first is the matter of delineating territorial waters and economic exclusivity zones (EEZ) for each individual nation that borders the South China Sea and how these areas may often overlap. The second issue are the legal rights to exploration and exploitation of oil and natural gas, mineral and renewable resources in the overlapping EEZs as well as the international sea zone that lies outside territorial and EEZ areas. The third matter of contention is the free passage of international commercial traffic and warships through United Nations delineated “International” waters.

At first glance it may seem easy to rely on the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1982) to resolve these issues; however, a number of factors make this quite difficult. UNCLOS exists in part to establish the legal status of territorial waters and to lay down a framework to determine who has the right to harvest the bounty of the world’s oceans both between nations with maritime borders and those that are land locked. It also sets up a legal framework for dispute resolution. This dispute resolution framework exists partly due to the fact that the adopted method for delineating EEZs often leads to overlapping EEZs between one or more nations. This is the case in the South China Sea. To add to the legal ambiguity, there are historical factors that only magnify the ambiguity. For example, who has right to the ownership of islands that no one has ever built permanent settlements on when their location was known for centuries? Now that vast oil and natural gas fields may lie under these remote areas that cannot independently support human habitation, a number of nations are claiming historical precedent to ownership regardless of their lack of utilization and the generally laissez faire attitude toward their sovereignty for hundreds of years.

China submitted an official case to the United Nations in 2009, laying out the Chinese claim to most of the South China Sea. What has come to be known as the “Nine Dash Line Claim” (which China has asserted in one form or another for years) asserts that almost the entire South China Sea is the sovereign waters of the Peoples Republic of China. China sights both historical factors and their interpretation of UNCLOS to support this claim. A group of nations bordering the South China Sea, and who have conflicting claims refute the Chinese position. A number of nations without any legal claim to these waters for purposes of territorial waters or EEZs, also refute the Chinese claim for a number of significant reasons.

The UNCLOS clearly specifies how the borders of a nation’s territorial waters are to be established and delineated:

Article 2

Legal status of the territorial sea, of the air space over the territorial sea and of its bed and subsoil

- The sovereignty of a coastal State extends, beyond its land territory and internal waters and, in the case of an archipelagic State, its archipelagic waters, to an adjacent belt of sea, described as the territorial sea.

- This sovereignty extends to the air space over the territorial sea as well as to its bed and subsoil.

- The sovereignty over the territorial sea is exercised subject to this Convention and to other rules of international law.

Furthermore:

Article 3

Breadth of the territorial sea

Every State has the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles, measured from baselines determined in accordance with this Convention.

Article 4

Outer limit of the territorial sea

The outer limit of the territorial sea is the line every point of which is at a distance from the nearest point of the baseline equal to the breadth of the territorial sea.

Furthermore, it less clearly specifies how the extent and borders of a nation’s Economic Exclusivity Zone (EEZ) are to be established and delineated:

Article 55

Specific legal regime of the exclusive economic zone

The exclusive economic zone is an area beyond and adjacent to the territorial sea, subject to the specific legal regime established in this Part, under which the rights and jurisdiction of the coastal State and the rights and freedoms of other States are governed by the relevant provisions of this Convention.

Article 56

Rights, jurisdiction and duties of the coastal State in the exclusive economic zone

- In the exclusive economic zone, the coastal State has:

(a) sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil, and with regard to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of energy from the water, currents and winds;

(b) jurisdiction as provided for in the relevant provisions of this Convention with regard to:

(i) the establishment and use of artificial islands, installations and structures; 44

(ii) marine scientific research;

(iii) the protection and preservation of the marine environment;

(c) other rights and duties provided for in this Convention.

- In exercising its rights and performing its duties under this Convention in the exclusive economic zone, the coastal State shall have due regard to the rights and duties of other States and shall act in a manner compatible with the provisions of this Convention.

- The rights set out in this article with respect to the seabed and subsoil shall be exercised in accordance with Part VI.

Article 57

Breadth of the exclusive economic zone

The exclusive economic zone shall not extend beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured.

(United Nationals Convention of Law of the Sea, 1982)

Obviously, these definitions were created by lawyers, as they are somewhat ambiguous and leave ample room for limitless future argument; such arguments guaranteeing lawyers a livelihood since time immemorial. They have created a patchwork of overlapping EEZs and legally agreed to or disputed territorial waters delineations.

The UNCLOS attempts to legally delineate territorial waters and provide for established EEZs for the benefit of coastal nations. That being said, it is quite easy to see that China has a much easier to justify claim, both historically and legally to most of the Paracel Islands. The majority of them lie in their EEZ, they have built settlements and installations on some of the islands, and they have fought and won at least two past naval engagements with Vietnam (in 1974 and 1988) to enforce sovereignty. A justifiable claim to the Spratly Islands or Scarborough Shoal by China is another matter altogether. The map below easily illustrates the established EEZs (as proposed under UNCLOS, which China is a signatory).

Map of EEZs and International waters in the South China Sea.

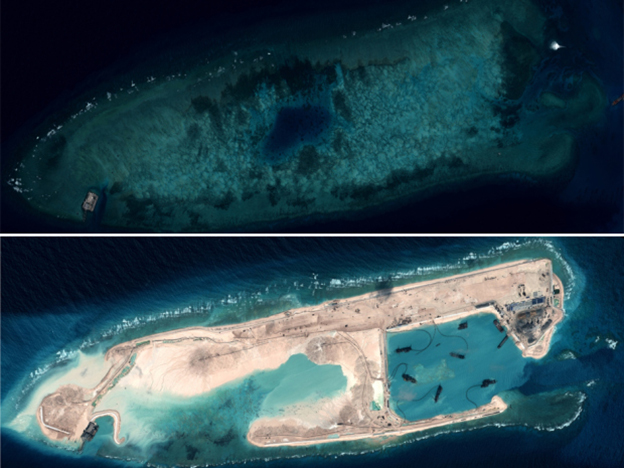

Apparently, China has decided to push their claim to a majority of the South China Sea by actually establishing habitation and extensive facilities of both commercial and military significance on a number of islands in both the Paracel and Spratly Island chains, as well as around Scarborough Shoal (although to a lesser extent there). China is clearly embracing the old adage that “ownership is nine tenths of the law”. When one considers this strategy alongside the significant Chinese modernization and expansion of its naval area control and denial capability in the past two decades, it is obvious that China aims to overthrow the current status quo. The old status quo does not support China’s interests, so they aim to change it. Other parties to the conflict, most notably the United States desire to maintain the status quo.

Chinese land reclamation efforts at Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly Islands August 2014 – January 2015.

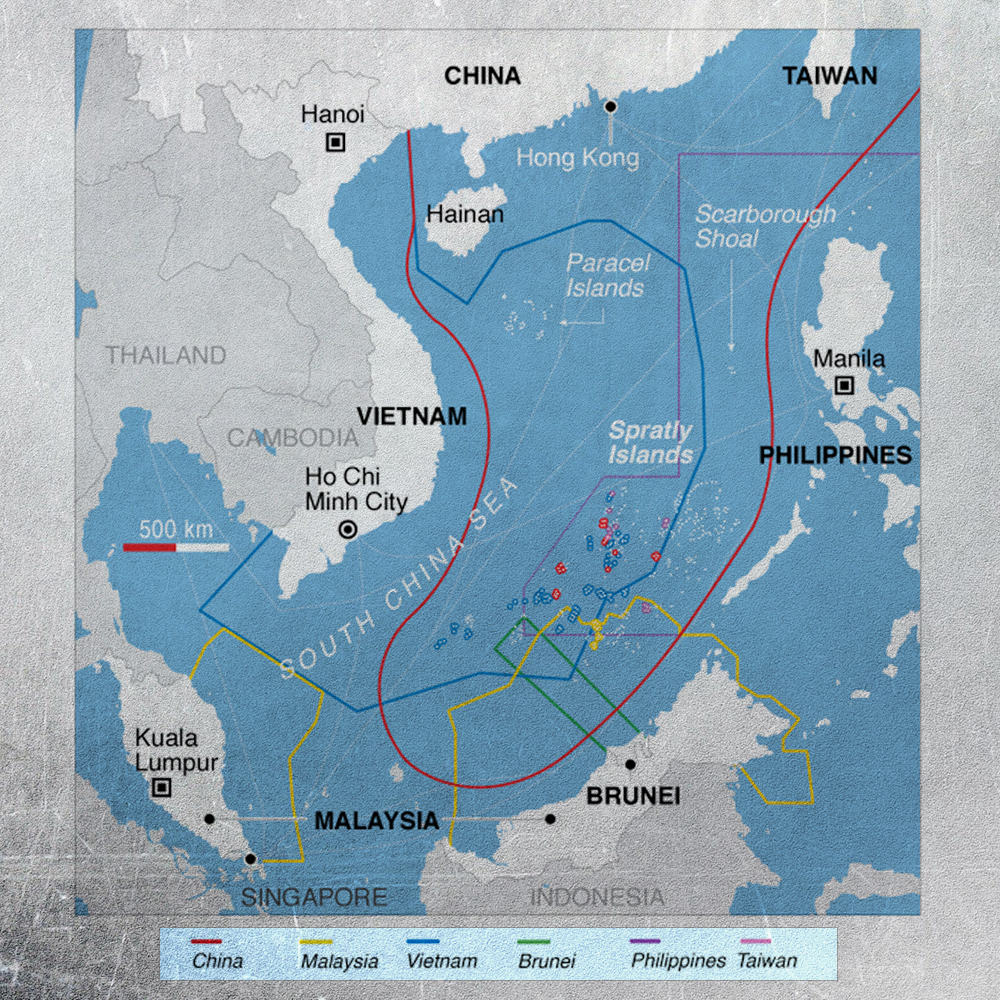

The nations other than China that are defined as coastal states under UNCLOS that also have conflicting claims to various parts of the South China Sea are Vietnam, The Philippines, Brunei, and Malaysia. Malaysia and Brunei have taken a somewhat subdued stance towards China, in light of their important trade relations, historical ties, and the relative balance of power considerations. The Philippines and Vietnam have decided to rely heavily on the support, both diplomatically and militarily, of the United States.

All of the above claimants have justifiable claims to the economic benefits inherent in the waters, seabed and arguable sovereignty to islands that lie within their EEZs. In confrontation with a much more powerful and industrious China, they have enlisted the aid of the United States in a number of ways. While all have welcomed the influence of the United States as an International mediator, both Vietnam and the Philippines have forged greater military ties in the areas of military cooperation and the acquisition of naval armaments.

The Philippines has somewhat ironically welcomed the United States back to reestablish a major naval base at Subic Bay, after decades of efforts to force the U.S. Navy’s eviction. Times change. The United States has donated vessels to the Philippine Navy in the form of decommissioned U.S. Coast Guard cutters and naval research vessels as recently as 2015. The Royal Australian Navy has donated a further two heavy landing craft (LHC). As part of the announced “Pivot to Asia”, the United States intends to re-forge defense agreements and a permanent naval presence in the Philippines.

Conflicting claims in the South China Sea

Vietnam has chosen a more tactful and nuanced approach. Vietnam has decided to seek international diplomatic support for its claims, diplomatic mediation, as well as a robust yet less ambitious naval modernization strategy. While the United States pledged $18 million (USD) to help Vietnam protect its territorial waters and coastline in June of 2015, a long-standing U.S. arms embargo is still in effect. Vietnam had been reliant on Russian naval arms for 40 years; however this is changing as Vietnam looks to supplement its relatively small navy with western armaments and patrol craft. Vietnam has chosen the strategy of building a more powerful and robust coastwise navy, planning to acquire more modern vessels of small displacement such as patrol boats, corvettes and frigates. This will bolster Vietnam’s territorial defense capabilities, while not fomenting an arms race that they have no hope of winning with their larger neighbor China.

Indigenously produced Patrol Boat TT-400TP of the Vietnam Peoples’ Navy underway.

The issue of freedom of navigation in international waters in the South China Sea is a valid concern by many “neutral” parties. This is a centuries old concept; that there should always be free and uninhibited commercial and military traffic (both on the water and now in the air as well) on internationally recognized waterways of the high seas. These international free transit corridors are a core foundation of international trade and cooperation that must always maintain their neutrality and absence of sovereignty. They, quite simply put, belong to all nations and individuals of the world for the purposes of transportation and commerce.

This age old concept is essential to maintaining what should be a universally embraced concept of equality amongst all peoples and all sovereign nations of the world and their equal and unequivocal right to commerce and peaceful pursuits on the high seas. The determination of the United States to defend this concept is honorable, just and essential; however, it is not through righteousness and altruism alone that the government of that nation has adopted such a stance. At some point in the past, when the United States still held the moral high ground and obeyed international law in all respects one could honestly come to such a conclusion; but any concept of truly altruistic intent in the geopolitical maneuvering of any nation is naïve. All nations act in their own interests, regardless of the nation, or the era of human history.

Three US Arleigh Burke Class DDGs on maneuvers in the Pacific.

The United States has an undeniable interest in keeping the South China Sea an international waterway, free of any national controls. An estimated $5 trillion (USD) in international trade passes through this waterway annually. It also has many self-serving interests in keeping the resources of this area divided amongst a host of claimants. As we have seen all too often in recent history, such as in the Middle East, the United States’ foreign policy has focused on the dissolution and fragmentation of power and resources of any potential single benefactor other than itself. In extremely simplified terms, it is a classic divide and conquer strategy. Sowing discord and disagreement in a regional dispute, while inserting an outside international influence of a military nature of magnified proportions, will do nothing but enflame the situation and lead not only to a regional naval arms race, but force all parties to look for a military solution where a combination of diplomacy and proportional military deterrence would have naturally provided a more equitable answer over time.

The simple fact is that the United States realizes that time favors China in this dispute. China has far more resources in diplomatic, economic and military terms to throw at determining this dispute in its favor than all of the other claimants combined. The United States needs to use its military power in a way that nullifies all parties involved and not as a buttress to the claims of those parties that it favors.

The current territorial disputes in the South China Sea have been festering for centuries, but the relatively recent discovery of significant oil and natural gas deposits in the area have added a sense of urgency and veracity that had been historically absent. As the nations in the region scramble for the necessary resources they will need to grow and prosper in the coming decades, they will inevitably be faced with disputes over legal rights to resources and sovereignty, and will be challenged to find a means by which to resolve these disputes. There currently exist both positive and negative influences on both the efforts of de-escalation and conflict resolution.

All parties involved apparently have legitimate claims to certain areas in dispute dependent upon legal grounds and historic precedent. None possess a legitimate claim to all of the areas that they have stipulated should fall under their UNCLOS jurisdiction or sovereignty. China clearly has no legally defensible claim under UNCLOS, or supported by any historical evidence of particular merit to all of the area included in their “Nine Dash Line” claim.

China is relying upon their own ingenuity, industry and force of will to develop these areas and make them their own in very material terms. They are occupying and developing islands that have never been used for human habitation of any significance, by anyone in the course of human history, at a scale that is unprecedented. In such a case, do they not have a claim of sovereignty to these islands, and if they do, to what internationally recognized extent? Does a nation that peacefully develops a previously barren area of the world not have any claim of sovereignty over it, when many nations claim sovereignty over land that has changed hands many times as a result of war and conquest? What legitimizes the claim of the United States to Saipan or Guam, or the claim of Britain to Gibraltar other than the argument of the legitimacy of imperial conquest or the favorable outcome of war in their favor? This is the very status quo foundation of sovereignty that China is challenging.

The United States can use its military might and diplomatic influence to mediate in an impartial manner in the cause of international law and the honorable and indispensable concept of freedom of navigation on the high seas. This would be a welcomed endeavor in the eyes of most nations of the world. The United States can also play a destructive and counterproductive role as the outside agitator and schoolyard bully, as it so often has done in international affairs in recent years. We can only hope that in the U.S., statesmanship and wisdom overcomes imperial hubris, and that in China, pragmatism overcomes ambition.