Written by Brian Kalman exclusively for SouthFront: Analysis & Intelligence

Brian Kalman is a management professional in the marine transportation industry. He was an officer in the US Navy for eleven years. He currently resides and works in the Caribbean.

Introduction

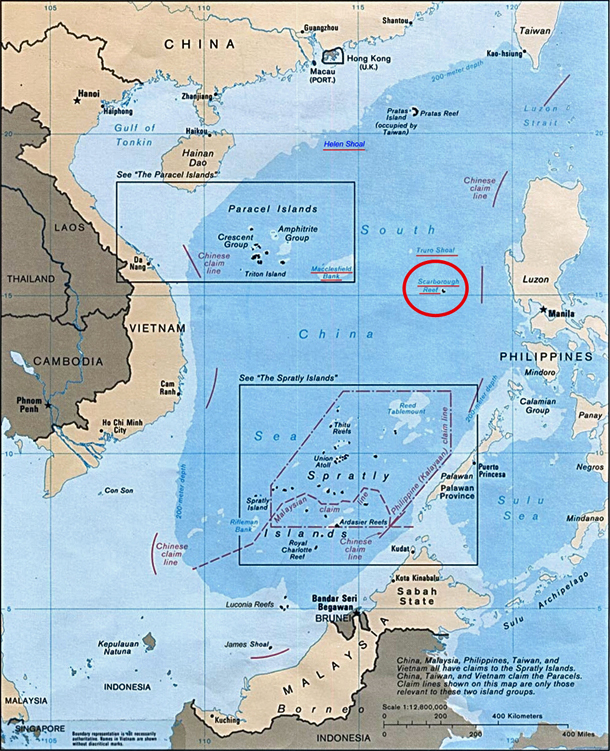

The Permanent Court of Arbitration based at The Hague is due to release its ruling on the case filed by the Philippines against China in January of 2013, over the Chinese seizure of Scarborough Shoal in 2012. The ruling should be made public in late May or early June of this year. The message has been communicated through unofficial channels via the state-run Chinese media that the Chinese government intends to commence major land-reclamation efforts at Scarborough Shoal during this same time period. Unlike its claims in the Paracel Islands and the Spratly Islands, China’s claim to Scarborough Shoal has absolutely no validity on either historical grounds nor any internationally recognized legal grounds, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

The United States claimed the shoal as a possession along with the entirety of the Philippines after Spain surrendered the territories to the U.S. upon the conclusion of the Spanish American War, as stipulated in the 1900 Treaty of Washington. The shoal was administered by the U.S. Navy until it was returned to the Philippines upon the nation’s independence in 1946. China laid no claim to Scarborough Shoal until the U.S. military officially closed its military bases in the Philippines in 1992. In 2012 they effectively took control of the shoal after forcing the Philippine Coast Guard, law enforcement and fisherman out of the area in a tense conflict that lasted for weeks. While avoiding a violent confrontation over the shoals, the Philippine government protested the Chinese actions in the United Nations and lodged legal challenges to the occupation of their sovereign territory.

Although the United States’ official position is that it will not back any claimants’ position in the many disputes in the South China Sea, the issue of Scarborough Shoal is unique in a number of respects. An understanding of the historical and legal status of Scarborough Shoal, coupled with a formal defense treaty with the Philippines makes impartiality in this particular territorial dispute impossible. As the United States reforges military ties with the Philippines in an attempt to contain a more ambitious and capable China, the odds of a conflict over ownership of the shoal only becomes more probable.

The location of Scarborough Shoal in relation to China and the Philippines.

The History of Sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal

The Philippines was claimed by Spain in 1521 by Ferdinand Magellan and administered as a colony under the authority of the Viceroyalty of New Spain in Mexico, until Mexico’s independence in 1821. By 1570 the Spanish had largely conquered the Islands, after defeating the Kingdom of Maynila (Manila) and had named the island nation Las Islas Filipinas after Philip II of Spain. With the completion of the Philippine referendum of 1599, where all natives of the islands declared Spain to be the rightful sovereign authority, Spain gained legitimate sovereignty over the entirety of the Philippine Islands.

Although Chinese pirates often raided the Spanish settlements and the ships of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade, the Chinese nation made no counter claims against the Spanish sovereignty in the area, and no one attempted to claim sovereignty over the diminutive shoal that we know today as Scarborough Shoal. The shoal gained its English name when the captain of the East Indiaman Scarborough, ran aground on the shoal in 1784. In 1898, the Spanish-American War resulted in the defeat of Spain, and the transfer of Spanish colonial holdings in the Caribbean and the Pacific to the dominion of the United States. The Treaty of Paris of 1898 and the subsequent Washington Treaty of 1900 legally formalized this transfer of territories. It is interesting to note that the sale of the Philippines to the United States as stipulated in the Treaties, for the amount of $20 million, was narrowly ratified by the U.S. Congress. There was a sizable minority of anti-imperialist sentiment in the U.S. Congress at this time.

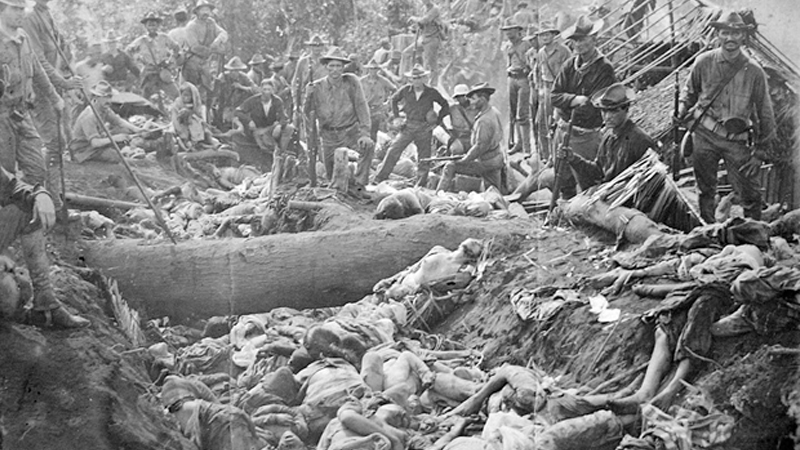

The United States then fought a war of colonial occupation against a vibrant Philippine Independence movement from 1899 to 1902 that would result in approximately 220,000 casualties, not including tens of thousands of civilians that died during the same time period, due to starvation and disease exacerbated by the war. The short-lived first Philippine Republic was defeated in this war, and the Philippines would have to suffer under one more foreign occupation, at the hands of Imperial Japan, before a new Republic was declared upon independence after World War II. The Treaty of Manila of 1946 between the United States and the Republic of the Philippines granted full independence; however, local governance and a high level of autonomy were the norm, beginning in 1916. In 1934 the U.S. Congress passed the Philippine Independence Act, effectively turning the Philippines into a self-governing Commonwealth. It was during this period that the Philippines first asserted a desire to administrate the Scarborough Shoal.

Aftermath of a battle between U.S. forces and Moro rebels during the Philippine-American War.

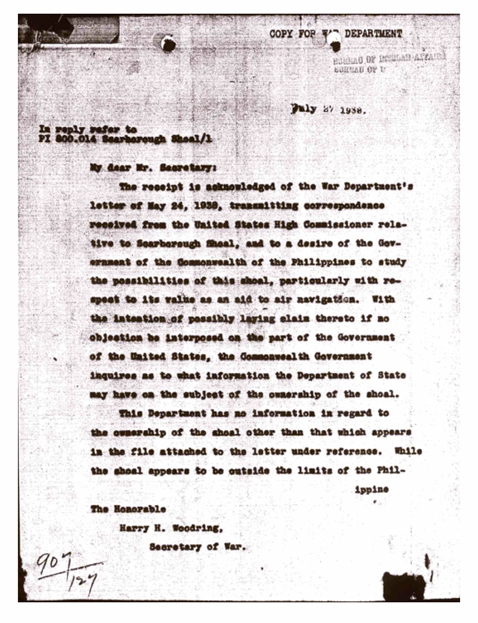

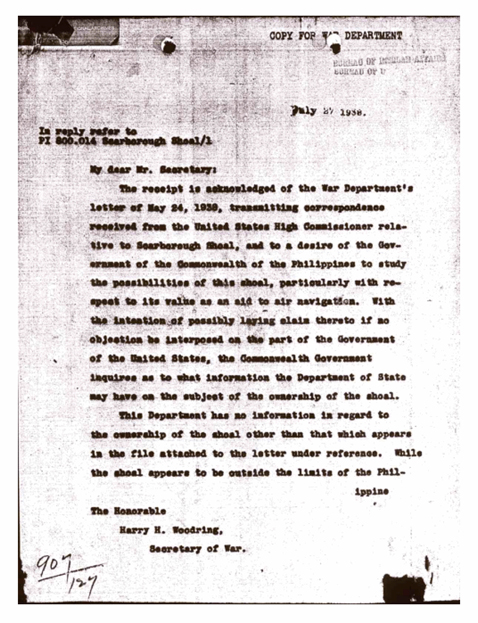

In 1938, the Commonwealth government asked the U.S. Department of War and the U.S. Secretary of the Navy for permission to develop the Scarborough Shoal as an aid to navigation for both sea and air traffic. The U.S. Navy had been administering the region for the purpose of safety of navigation, as well as naval gunnery training. Official correspondence from the U.S. Secretary of War, Secretary of the Navy, and U.S. Civil Aeronautics Authority clearly show the acknowledgement that Scarborough Shoal is a sovereign territory of the Philippines, and that the U.S. government agrees to cede all practical administration of the shoal to the Commonwealth of the Philippines, later to become the Republic of the Philippines. A letter from the U.S. Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, to the U.S. Secretary of War, Harry Woodring, regarding the matter, stipulates the position of the U.S. government at the time and is listed in its entirety below:

The Scarborough Shoal Stand-off of 2012

China did not raise any official objections to the inclusion of Scarborough Shoal as an integral sovereign territory of the Philippines as a colony of Spain, the United States or as an independent nation as of 1946. From 1599 to 1946, a period of 347 years, there were no Chinese claims of sovereignty over the shoal. For an additional 46 years, from the date of Philippine independence to the official closure of the last U.S. military base operating at Subic Bay, China did not dispute Philippine sovereignty over the Scarborough Shoal. Shortly after the U.S. ensign was lowered for the last time at Subic Bay Naval Base, China started a diplomatic effort to dispute the sovereignty of the territory.

After the most recent four centuries of Philippine history was absent of any counter claims of sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal, China opportunistically raised the issue in 1991 when they estimated the Philippine government, absent a strong U.S. military presence, to be most weak. While it would have been logical and legal according to all international norms for the Philippines to reject outright such claims, the Philippine government, under President Fidel Ramos, decided to set upon a path of de-escalation and to prevent the militarization of the issue. In 1995, both governments signed an agreement adopting a code of conduct that committed both nations to resolve the issue through peaceful, political means. This would turn out to be a major strategic mistake by President Ramos.

The Scarborough Shoal remained de-militarized and was visited intermittently by both Chinese and Philippine fisherman, and civilians engaged in various marine biology, weather and oceanographic survey projects. Although there were minor incidents regarding illegal fishing in the vicinity of the shoal, no major disputes arose. Scarborough Shoal was an international gray area ripe for an emergency.

The second major strategic mistake on the part of the Philippines, was the drafting and passage of Republic Act No. 9522, the Philippine Archipelagic Baselines Law in 2009. The administration of President Arroyo deemed it essential to define the limits of the Philippine Archipelago to mirror as closely as possible the definitions set forth in UNCLOS. In order to be more compliant with an international legal treaty, the Philippine government redefined the boundaries of their nation in a fashion that dissenting senators declared was “a sellout of national Philippine sovereignty.” Both the Kalayaan Islands (Spratly Islands) and Scarborough Shoal were excluded from the extended continental shelf (ECS) of the archipelago as a whole. In the same year, China presented its famous “Nine-Dash Line” claim to the United Nations, claiming almost the entirety of the South China, including Scarborough Shoal.

The peaceful status quo was maintained until April 10th, 2012, when the Philippine Coast Guard interdicted and apprehended a group of Chinese fisherman for conducting illegal fishing practices on the shoal. Chinese “civilian research vessels” interdicted and prevented the arrest of the Chinese fishermen the very next day. This precipitated what came to be known as the Scarborough Shoal Stand-off. A tense situation, where both Chinese and Philippine civilians planted their respective national flags on the shoal, fishermen from both nations clashed with Coast Guard vessels flying Chinese and Philippine colors soon followed. The diplomatic corps of both countries spared with increasingly nationalistic statements over the intervening months. Finally, in June the United States was able to broker a deal between both nations in which they both agreed to withdraw all forces from the shoal in an effort to deescalate the situation, and to rely on diplomatic means to resolve the dispute. The Philippines honored this agreement and withdrew all navy and coastguard vessels and personnel. China; however, immediately reneged on the agreement and reinforced their position on the shoal, building a barrier blocking its south-eastern entrance.

The Philippines responded with diplomatic and legal protests, refraining from getting involved in a military confrontation with a much stronger China. The Philippines lacked the naval and air power to evict the Chinese from the shoal and to hold it against a determined Chinese assault. They did not possess the resources for a viable anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capability at such a range from the main islands. On January 22nd, 2013, the Philippines instituted arbitration proceedings through the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, an internationally respected arbitration court that was founded in 1899. While not technically a court in the traditional sense, the PCA was established as a framework of international tribunals meant to resolve major legal disputes between states.

The Scarborough Shoal Today; The Spark That Will Ignite the Powder Keg

As the PCA approaches a decision on case number 2013-19, The Republic of the Philippines vs. The People’s Republic of China, over the coming months, China is preparing to begin major land reclamation efforts at Scarborough Shoal. As most legal analysts believe that the PCA will most likely rule in the favor of the Philippines, major construction efforts on the shoal by China are extremely provocative and will undoubtedly raise tensions between the two nations, as well as exaserbate a series of other territorial disputes between China and other nations bordering the South China Sea.

China most likely aims to build a major early warning radar installation and airfield on the site of Scarborough Shoal, to complete a larger network of such installations that will allow it effective A2/AD capability over the entire South China Sea. What some analysts have dubbed a “Strategic Triangle”, the major base on Woody Island in the Paracels, and the bases currently being completed on Fiery Cross Reef, Mischief Reef, Subi Reef and Johnson South Reef in the Spratly Islands, form two points of the triangle. A similar base on Scarborough Shoal would form the third point, and close the triangle of strategic control over the South China Sea.

The location of Scarborough Shoal in relation to the Paracel and Spratly Islands.

The United States and the Philippines conducted joint military exercises over a period of eleven days this April. Operation Balikitan (Shoulder-to-Shoulder) involved approximately 10,000 personnel from both nations’ militaries, and simulated amphibious assaults, interdictions and boarding of hostile vessels at sea, and joint naval and air maneuvers. The military exercises were aimed at practicing cooperative efforts between the U.S. and Philippine militaries, and to send an obvious message to China that both nations are ready and willing to respond to military provocations. Perhaps more controversial than U.S. military cooperation with the Philippines, was the visit of Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force vessels to Subic Bay at the same time. The JS Oyashio attack submarine and two guided missile destroyers, JS Ariake DDG 109 and JS Setogiri DDG 156, docked in Subic Bay on April 3rd.

The JS Oyashio, JS Ariake and JS Setogiri dock in Subic Bay, north of Manila April 3, 2016.

Whether land reclamation efforts by China at Scarborough Shoal will be interpreted as a direct violation of Philippine sovereignty or not remains to be seen, but the added influence of a PCA ruling in favor of the Philippines may add extra impetus for such a decision. Backed by an internationally recognized legal decision by an organization of the highest reputation, the Philippines will have added legitimacy in demanding that China halt all activity and vacate Scarborough Shoal. If China refuses, and the Philippine military decides to forcible evict Chinese forces and enforce Philippine sovereignty of the shoal, will the United States intervene on the side of the Philippines if a violent military confrontation ensues?

The United States is bound to defend the Republic of the Philippines if attacked. The Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement was upheld by the Philippine Supreme Court just this January, after the constitutionality of the treaty was challenged in 2014. This Act gives the United States broad access to base military assets at five major bases throughout the Philippine Islands, and reinforces the Mutual Defense Treaty between the two nations. The treaty stipulates that both parties are obligated to defend the other if an armed attack is carried out “on the metropolitan territory of either of the Parties, or on the island territories under its jurisdiction in the Pacific.” This treaty would only be binding on the United States if the sovereignty of the Scarborough Shoal is finally determined and broadly recognized internationally.

Conclusion

It is easy to see a major confrontation over the sovereignty of Scarborough Shoal occurring this summer, as a confluence of events and legal decisions sets the stage for resolving a long standing dispute, one way or the other. China has used different strategies to advance its interests in the South China Sea. In the Paracel Islands, where China has legitimate legal and historic claims to at least some of the islands, military force was used to reinforce these claims. They fought and soundly beat the naval forces of the Republic of Vietnam in 1974 and immediately occupied the islands. In the Spratly Islands, China has used a mix of diplomacy, military force and the unprecedented efforts to build artificial islands, to claim sovereignty over these territories. Chinese claims in the Spratly Islands do not meet the legal requirements as stipulated in UNCLOS, and claims on historic grounds are quite flimsy and inconclusive. In this case, China has wisely decided to exercise sovereignty through island development and occupation.

Republic of the Philippines Marines practice small scale amphibious landing operations during Balikitan 2016.

China has chosen this last strategy in exerting sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal, as its legal and historic claims carry no weight. Much hinges on the ruling of the PCA and Philippine efforts to garner international support via unilateral diplomatic efforts and through the United Nations, if the ruling of the arbitration turns out in their favor. If Philippine sovereignty is broadly accepted internationally, then a major military confrontation may be very probable. As the governments of China, the Philippines and the United States set their respective courses and continue to solidify their strategies over this territorial dispute, in consideration of broader regional and global strategic issues, the chances of a major military confrontation increase exponentially.

It is hard to conduct a simple cost-benefit analysis of a confrontation for any of the parties to this potential conflict, as it is impossible to know just how much any of these parties are willing to sacrifice in pursuit of their strategic aims. What is known, is the possible outcome of any military confrontation when carried to its furthest escalation; thermonuclear war between China and the United States. The U.S. test-launching of multiple Minuteman III ICBMs off the coast of California late last year, and the similar test-launch of a DF-41 ICBM into the South China Sea by China on April 12th, speak volumes as to the messages being sent by Washington D.C. and Beijing. Although successive Philippine administrations have been keen to deescalate the dispute in the past, the prospect of a major military installation of a foreign power being built only 130 miles from the national capitol, clearly changes the strategic calculus of Manila. One way of the other, a major compromise or escalation is bound to occur over the next few months.

PRC (+ Hong Kong) are major trade partner… (circa 20.5% of Filipino exports)

I very much doubt the Philippines can afford damage to the economy, over a shoal.

The Philippines are used to having major military installations of a foreign power, much closer than 130 miles away from their capitol, that the article cites as a concern.