Written by Daniel Edgar exclusively for SouthFront

Although paramilitary groups have a long history in Colombia (at least thirty to fifty years depending on how they are classified and by whom) their size, resources, capacity for military operations and the extent of overt and covert linkage and collaboration between the paramilitary groups and the security forces (military, police and intelligence) of the State peaked from the mid-1990s until 2005, by which time the many disparate groups and fronts that the paramilitary phenomenon produced had developed a unified national umbrella structure (las Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia, AUC – the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia).

The wide ranging scale and extent of mutual penetration, collaboration and shared interests and objectives that existed between the paramilitary groups and the armed forces extended to all of the other branches and agencies of the State to include many local, provincial and national level politicians, bureaucrats and magistrates, as well as having a major impact on and mutual penetration of just about all economic activities, from extortion of local businesses and commerce to the conduct of massacres to clear arable or strategically important land of its inhabitants, as well as an infinite diversity of direct or indirect ongoing cooperative relations with all manner of businessmen, companies and sectors in the economy. Many “foreign investors”, including some of the largest transnational companies with a significant presence in Colombia, have also been accused of direct and/ or indirect collaboration with paramilitary groups and of benefiting from crimes committed by members of those groups against their employees and communities located where they have major projects, including British Petroleum, Chiquita Brands (United Fruit Company), Coca Cola and Nestlé

While many paramilitary groups were formed directly by large landowners, businessmen and/ or drug cartels in regional and urban areas to combat the guerrilla groups, many others were established or massively expanded and directly supported by the armed forces of the State (including international military officials and advisors, in particular from the United States, Israel and the United Kingdom) to assist in the fight against the various guerrilla groups. Although the paramilitary groups were generally organically connected to elements within the Establishment and owed their creation (and impunity for their criminal activities) to them, as time passed and they became more powerful many of them began to act with increasing degrees of autonomy and some entered into direct confrontation with the Establishment (whether manifested by the local and regional political and economic elite, the security forces or the national government) over particular topics and in particular areas. Despite the consolidation of the national umbrella structure many of the paramilitary groups also frequently fought amongst themselves for control over territory and resources, while some entered into tactical alliances with local fronts of guerrilla groups for specific purposes and activities.

The paramilitary groups were officially demobilized following the signing and implementation of an agreement with the national government of President Álvaro Uribe in 2005, however many critics claimed that the process was not really intended to end the paramilitary phenomenon but was rather an attempt to distance such groups and activities from the State and the Establishment, supporting these claims with arguments such as that only a small number of their weapons were handed in, that many former members refused to demobilize and proceeded to form smaller and more anonymous groups, and that many of the activities in which they were engaged continued to take place with little or no noticeable change from the perspective of the sectors of Colombian society that had suffered the most from the paramilitary groups´ activities (including farmers and rural and remote communities, Indigenous people, leftist and independent political organizations and social movements, trade unions and human rights defenders).

The paramilitary groups were usually described as “ultra-right wing” given their traditional role as blood enemies of and counter weights to the communist and extreme left wing guerrilla groups and their support for and cooperation with the political, administrative and economic institutions of the Establishment which was in turn controlled by what could be generically described as right to far-right wing political parties and groups. Nonetheless, apart from their vitriolic hatred of the guerrilla groups there was never anything resembling a coherent ideological basis or line of reasoning underpinning the existence and activities of the paramilitary groups, the only other common factor amongst them being the use of extremely brutal forms of violence to achieve immediate military, political and economic goals and objectives and total control over the population through fear and terror. This is readily apparent from a cursory reading of the pamphlets or the text of the death threats that they make, all of which follow a very basic and brutal script; a copy of one such document is attached and translated at the end of this article.

This has become increasingly apparent with the successor groups that formed following the formal process of demobilisation. The government refuses to consider them as being in any way related to the paramilitary phenomenon, referring to them generically as “bacrim” (an abbreviation for criminal gangs, bandas criminales) and “groups at the margin of (or beyond) the law” (grupos al margen de la ley). Of the approximately eight major groups that currently exist falling within this category, all of them are heavily involved in illegal economic activities and it is arguable that some or even most of them are now largely or exclusively devoted to such pursuits and could be considered conventional (that is, non-political or apolitical) criminal gangs and organized crime networks.

Nonetheless, several of the successor groups are still fulfilling some of the political roles and objectives that the paramilitary groups performed (in particular the functions of clearing land for large scale agricultural and natural resource projects, and maintaining ironclad social control over the population by instilling fear and terror amongst large sectors of society), albeit without the obvious organic links to the State that characterized the organizational structure, membership and operations of their predecessors.

Two of the largest successor groups are particularly prominent in this regard, the Urabeños (also referred to as the Usaga clan) and the Águilas Negras (Black Eagles). The former appears to have an ambiguous and multi-faceted relationship with the Establishment as such. It is hostile to the current government of President Juan Manuel Santos, which has managed to capture and prosecute many of the leaders of the group; in response, the Urabeños have killed many police officers, and in a recent show of strength imposed a 48 hour shutdown in the provinces where it has a substantial presence that paralysed all economic and administrative activity and transport in six provinces in the north of Colombia. However, at the same time it expressed willingness to negotiate its demobilization with the government on the basis that it has a unified command structure and a sufficient degree of permanent military activities and territorial control to be considered a belligerent political armed group in accordance with international laws and norms. The government of President Juan Manuel Santos has so far flatly refused to consider the possibility of negotiating with the group on such a basis or on any terms other than their unconditional surrender to the proper authorities.

Another complicating factor is that the shutdown imposed by the Urabeños in the north of Colombia coincided with anti-government rallies convened throughout the country by far right wing political parties and forces protesting against the negotiations the government is undertaking with the two remaining guerrilla groups (the FARC and the ELN); the protest was led by former president Álvaro Uribe, thought by many to have been a key supporter and beneficiary of the paramilitary groups prior to and during his time in office (from 2002 to 2010). Many social organizations and representatives in the areas in which the shutdown and the political protest overlapped have claimed that the Urabeños actively assisted the political protest, including through providing logistics and offering other incentives to participate, raising the possibility that beyond the confrontation with the government of the day there may still be significant collaboration with, or at least common interests and objectives shared by, other elements within the Establishment that remain dedicated to former president Uribe´s policy of all-out war against the guerrillas (complemented by simultaneous collaboration with the paramilitary groups and their successors).

The Urabeños have also been one of the most active of the successor groups in threatening and assassinating the same individuals, organizations and sectors of society that were targeted by the paramilitary groups, suggesting a significant degree of continuity in the paramilitary project albeit in a new guise and political context. One of the other groups that most suggests the continuity of the paramilitary project is the Águilas Negras (Black Eagles), which emerged shortly after the official demobilization process and within a few years had the capacity to issue death threats (and carry out such threats) against all of the sectors and groups previously targeted by the paramilitary groups throughout most of Colombia. Nonetheless, the leadership, organizational structure and size of the group remains largely unknown, to the extent that many question whether it really exists as an integrated organization or loose alliance of organizations or is a nom de guerre used by a large number of crime gangs to instil fear and terror, is a generic term used by the press and the government to refer to unidentified successor groups of the paramilitary groups and other crime gangs, and/ or whether it may be used to cover the existence of some other apparatus of State terror to disguise the identity of those responsible for the ongoing systematic assassination of individuals, organizations and sectors of Colombian society targeted by the Establishment for elimination (pursuant to the doctrine of National Security of the 1970s and 1980s mentioned in the articles below by Alvaro Villarraga Sarmiento and Jose Honorio Martinez, which it turn had its antecedents in the counterinsurgency strategy of the 1960s espoused by US military advisors as discussed in the article by Jose Honorio Martinez).

Two recent articles from the Colombian press and an earlier analysis conducted by the organization InSight Crime – Crimen Organizado en las Américas discuss the ways in which the paramilitary phenomenon has evolved and mutated over time, translations of which follow.

“The Usaga aren´t simple delinquents: an interview with Álvaro Villarraga Sarmiento”

By Marcela Osorio Granados

Alvaro Villarraga Sarmiento, a researcher from the Centre of Historic Memory and director of the Foundation of Democratic Culture, conducts a radiography of the illegal organization and calls attention to the need to understand the dimensions of the neo-paramilitary groups in the current social and political contexts of the country.

Five people dead, a blockade of 36 municipalities in eight provinces and a sea of doubts and fears, that was the outcome of an armed shutdown decreed by the so-called Usaga clan last week that succeeded in demonstrating, in just two days, the reach of its networks and the consolidation of the power base that it has been building over the last few years. Alvaro Villarraga Sarmiento conducts a radiography of the criminal group and explains why the Usaga can´t be considered to be just a band of criminals.

How much influence does the Usaga clan currently have in the country?

The group, which calls itself the Gaitanist Self-Defence Forces of Colombia and is popularly known in many regions as the Urabeños and which the authorities refer to as the Usaga clan, has a very high level of power at this time. After years of disputes with other inheritors of the former dominions of the paramilitary groups, particularly the Rastrojos, they have achieved a clear hegemony. It is now a powerful group, a mixture of legal and illegal elements and activities, it cannot be underestimated and it cannot be understood as a simple phenomenon of delinquents. It is a delinquency of such power that it maintains connections and alliances in politics, with a significant degree of support among social and economic networks and the ability to exercise a certain degree of control together with its allies at the local and regional levels.

Why do they present themselves as the Gaitanist Self-Defence Forces?

The Usaga clan is a direct descendant of the paramilitary groups, that is something that is well known. They are groups that never demobilized completely, in this case reactivating their structures based in the provinces and regions of Atrato, Uraba and the south of Cordoba in the north of Colombia. Later they expanded towards Catatumbo, the Caribbean regions and along the Pacific coast, also establishing a presence along the middle reaches of the Magdalena River and on the Plains in the mid-eastern parts of Colombia. These facts demonstrate that we are not dealing with a limited phenomenon of criminal banditry but with an organized criminal structure that can now defy institutional power, co-opting and penetrating public and economic institutions and putting them to their service.

How many members are they estimated to have in the organization?

Any number you could mention would be an approximate estimation given the illegal nature and modus operandi of the group. In the report that we published at the Centre of Historic Memory at the end of 2015 we reviewed a variety of estimates from official sources as well as from organizations that have been investigating these types of groups suggesting that the group could have around 6,000 members. To be more specific, they do not operate in the same way that the guerrilla groups do, with permanent uniformed and dedicated formations constantly undertaking assigned military actions or other collective tasks. While they do maintain some sub-regional armed formations that possess a certain level of military capability, more generally the group consists of complicated clandestine networks complemented by informal associations and the contracting of independent individuals and groups such as assassins or local and regional criminal gangs that dominate specific activities such as the cultivation, production and distribution of cocaine or other illicit economic activities. They have also penetrated legal economic sectors and activities like taxi services.

You speak of relations with legal economies and institutional connections. Is there also active collaboration with the armed forces?

There has been a significant change between the para-militarism that existed before and that which exists now. We are no longer talking about the systematic national level of permissiveness, collaboration or inactivity of the armed forces that existed during the 1990s up until the demobilization of the AUC (the national umbrella structure of paramilitary groups) in 2005. These days such groups maintain systems of alliances with or corruption or intimidation of the authorities, particularly at the local and regional levels. However, there are also cases of local agents that establish long-term commitments and relationships with the groups.

Some say that during the recent armed shutdown that affected many regions in the north of Colombia the Usaga clan used language with political overtones…

During the recent so-called armed strike or shutdown the group demonstrated a clear intention in its pamphlets and pronouncements. It appears that they are trying to send a message seeking political recognition. This is apparent in the use of phrases that make reference to sharing the processes and the dynamics of peace that are occurring in the country; they also argue in the pamphlets that they satisfy the conditions of territorial control, capacity for sustained military actions and possession of a unified and responsible command structure. This is particularly notable because these arguments form the basis for recognition as a belligerent group involved in an armed conflict, and from there some form of political recognition, according to the principles of international law. I don´t share this interpretation that the successor groups satisfy the conditions for political recognition of the type that has been accorded to the guerrilla groups. They are not armed groups formed with an inherent political character and objectives, as is the case with the insurgent groups (the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, FARC and the National Liberation Army, ELN). Rather, the groups that emerged following the demobilization of the paramilitary groups are an expression of illegal economies, with the resultant emerging sectors and alliances founded in inequality and the lack of conventional opportunities in order to get rich through illegal economic activities and the violent expropriation of goods and resources by way of systematic attacks.

So what should the government´s strategy be: combat or negotiation?

The government now has the opportunity and the necessity to reconsider its strategy of combating these types of groups to the exclusion of any other approach. The government is obliged to recover territorial control, combat illegal economies, and dedicate itself completely to eliminating the opportunities for illegal economies and armed groups to flourish. This will not be easy given the riches to be made and the niches of power that the armed groups have managed to occupy, traditionally the domain of the paramilitary groups during the course of the last two or three decades. While nothing should be excluded outright, what is certain is that the purely military strategy that has been utilized up to now, involving direct combat and persecution, has been defective and insufficient because it is not based on an adequate understanding of the dimensions of the phenomenon.

Because it is worth pointing out that the Usaga clan are just a part of the problem…

Exactly. Underlying the existence of the current groups is the fact that the principal factors behind and causes of the paramilitary phenomenon have not been resolved. We are now in a more degraded phase of para-militarism that continues to afflict the country, although the groups themselves are weaker than they were before. While the media has adopted and popularized the phrase “criminal gangs”, the term is inaccurate and inappropriate as it reduces the topic to a phenomenon that pertains exclusively to the excesses of groups of delinquents seeking personal gain. However, over the last few years the groups that remain have become the principal violators of human rights on the country. They are committing more than 600 grave violations of human rights a year, clearly a factor that must not be ignored or underestimated. Apart from that, although we are no longer at levels near those reached during the late 1990s in terms of the number and scale of massacres committed throughout the country annually, it is very concerning that some categories of violations of human rights have not seen a reduction in frequency and intensity, and some have even increased during the existence of these new armed groups. For example, the number of forced displacements has not reduced and remains at an extremely high level, with close to 300,000 people violently displaced from their land and their homes each year.

Is there a direct relation between the consolidation of these groups and the recent denunciations of threats and attacks against leaders of leftist political parties and social movements as well as defenders of human rights?

We have to be clear about one thing: the doctrine of National Security is still being applied in the country. This is the doctrine of the internal enemy which involves attacking civilians – whether they are called Patriotic March (Marcha Patriótica), the Congress of the People (Congreso de los Pueblos), two leftist social movements, or people trying to reclaim land that they were violently displaced from – because they are considered to be connected to or collaborating with the armed insurgency in some way. We would like to think that this is no longer the case but unfortunately it continues to be supported by some sectors within the State. For example, the number of threats has increased. Regrettably, what has happened over the last few months is that as the momentum of the peace process has increased the threats against and assassinations of civil leaders, political activists and others close to the peace process has also increased in a manner that has clear political undertones and objectives. It is a grave fact for the country that the Patriotic March is saying that 120 of its members have already been assassinated. Members of the Congress of the People have also been assassinated, as well as representatives of people trying to reclaim land that they were violently displaced from, women and human rights defenders.

So can we talk about connections between the armed groups and political groups?

Many academic studies, reports by NGOs and other analyses of the topic have found that there is no doubt that these developments stem from the paramilitary phenomenon that resulted in the so-called para-politics scandal (in which many members of the national Congress as well as politicians at the provincial and local levels were investigated and prosecuted for links with paramilitary groups). Although the number of high level relations between paramilitary groups and senior public officials has declined, it must be acknowledged that there are still substantial levels of collaboration at the local and provincial levels as well as within State institutions more generally, and that substantial amounts of money derived from prohibited drugs and other illegal economic activities continue to be present and have a distorting effect throughout the political, social and economic activities of the country. Let´s not lie to ourselves, such groups and illegally obtained funds continue to elect governors and mayors and create and control political parties and groups. The judicial procedures that have occurred up to now have not been sufficient to resolve the problem. Also there are still many public officials that in effect inherited their posts from those that were prosecuted and imprisoned for para-politics, including their wives, children, and other relatives and close associates. That is the reality in Colombia.

Challenges for the government after the signing of peace agreement with the guerrilla groups: What is the principal risk that the new armed groups and structures represent to the prospect of a post-conflict era following the conclusion of peace agreements with the FARC and the ELN?

If the guerrillas agree to disarm and the peace processes reach a successful conclusion, the government will face an enormous challenge. The State cannot afford to fail institutionally as it did following the previous peace processes when it proved to be incapable of recovering control over the national territory. This time it is absolutely necessary that the nationally territory is recovered and not just in the geographic sense and from the point of view of the armed conflict against the guerrillas, but in terms of the vitality of the constitutional State based on the rule of law and a firm guarantee of the civil rights and freedoms of all Colombians, underpinned by cutting off the foundations of the illegal economies with socially oriented policies and effective plans for the substitution of illicit crops. They are enormous tasks, but they are the heart and soul of the peace process. We don´t want the disarmed members of the FARC and the ELN to face the same situation that was faced by the members of the M-19 and the EPL when they disarmed in the 1980s, following which they had to leave their homes and regional areas en masse because they were being systematically hunted down and killed. That can´t occur again, members of the guerrilla groups that agree to return to civilian life must have genuine and effective guarantees of their safety and civil and political rights that include the entire community and social networks to which they belong.

The preliminary agreements that have been reached during the peace process already provide a set of commitments on behalf of the State to provide such guarantees if they can be successfully implemented.

Statistics: According to the data of the National Centre of Historic Memory, illegal armed groups directly or indirectly derived from the demobilization of the paramilitary groups have a significant presence in 339 municipalities in the country (out of a total of approximately 1,100). The so-called Usaga clan is present in 119 of those, the Rastrojos in 76 and the Aguilas Negras in 39.

SOURCE

“Los Usaga no son simples delinquentes: Álvaro Villarraga Sarmiento”, by Marcela Osorio Granados, El Espectador, 2 April 2016

“Who are the Black Eagles?”

The Black Eagles were born from the failures of the demobilization process of the paramilitary groups that was carried out between 2004 and 2006, the stated objective of which was to disarm the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC). They are a fragmented group dedicated to protecting the economic interests of the mid-level commanders of the paramilitary groups dispersed throughout Colombia (most of the high-level commanders, who also ended up having high public profiles, were extradited to the United States to serve long jail terms). The “Black Eagles” was a generic term used by the government to describe the remnants of the paramilitary groups that were heavily involved in the trafficking of prohibited drugs throughout Colombia. In many cases the successors of the paramilitary groups have continued threatening and assassinating journalists, lawyers and human rights activists, identifying themselves as members of a group called the Black Eagles. This political tendency and the lack of a central leadership structure distinguish the group from other criminal gangs that operate in Colombia.

The groups that utilize the name Black Eagles have appeared in at least 20 of Colombia´s 32 provinces including Nariño, Cauca, Casanare, la Guajira, Magdalena, Bolivar, North Santander, Santander, Sucre and Cordoba. However, the groups appear to function independently from each other and they don´t respond to a central command. Each cell of the Black Eagles concentrates on the protection of its respective territory and competing with rivals such as the Urabeños and the Rastrojos.

Origins

The AUC was a federally structured organization of death squads – some of which were formed in the 1980s – which concentrated their efforts on achieving two principal objectives: the first, to fight against the leftist guerrillas, and the second, to make money, most of which came from drug trafficking. An important faction led by Carlos Castaña attempted to emphasize the ideological purpose and objectives of the AUC, presenting the group as a right wing political organization. This only resulted in more internal ruptures between the groups comprising the national federal structure of the AUC and the fragile coalition broke up. At the same time many of the leaders competed amongst themselves for territory, often in the midst of horrifying massacres and violent displacements of civilians. On 15 July 2003 the AUC agreed to initiate negotiations with the government. In return for dismantling their paramilitary forces and cooperating with investigative and judicial processes, the high level commanders were promised a certain degree of amnesty for the crimes they and their forces committed. A series of important processes pursuant to which specific groups disarmed followed and by 2006 31,671 supposed paramilitaries had demobilized.

However, the demobilisation ended up being a false peace. The majority of the paramilitary blocks only surrendered a small fraction of their weapons. Some young men were paid to falsely present themselves as combatants of the AUC while the mid-level command structures remained intact. Throughout the country small units of armed urban militias were maintained. In the rural zones, former paramilitary members continued to manage the ill-gotten properties, businesses and illegal economic activities of the paramilitary groups in the guise of civilians: the protection of coca plantations, the extortion of land owners and local businesses, the persecution of human rights activists, among many others. In contrast to the blocks of the AUC as they existed prior to 2004, the majority of the successor groups no longer dedicated themselves to fighting against the leftist guerrilla groups. In effect, some of the neo-paramilitary groups sought alliances with their former enemies, as occurred between the Popular Anti-Terrorist Revolutionary Army of Colombia (ERPAC) and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

It was early in 2006 that armed groups began to call themselves “Black Eagles”, in Cucuta in the province of North Santander and in some áreas in the province of Nariño. In North Santander it was probably former members of the paramilitary group “Catatumbo Block” who operated in the región from 1999 until their official demobilization on 10 December 2004. It is believed that in Nariño they were former members of the “Block of Liberators of the South” which had officially demobilized on 30 June 2005. Other armed groups calling themselves the Black Eagles soon appeared in Antioquia and along the Caribbean coast, appearing in Cordoba for the first time in 2007. These other formations of combatants were probably established by former members of the fourteen blocks that made up the “Northern Block” of the AUC, the coalition of groups of the AUC that controlled most of the territory in Colombia north of Antioquia.

On other occasions, Black Eagles was a generic term used by the Colombian press to refer to the former paramilitaries that continued to traffic drugs in specific territories. For example, the organization led by Daniel Rendon Herrera, formed by ex-combatants of the Elmer Cardenas Block (and that would later become the Urabeños), was at one time described as the “Black Eagles of Uraba”. The drug traffickers of the post-AUC era that operated in Antioquia and Cordoba were referred to as the “Black Eagles of the North”. On other occasions, the death threats against groups of lawyers, defenders of human rights and trade union leaders have been made in the name of the Black Eagles. Trade unions, social support agencies and activists trying to reclaim land from which they were violently displaced have received similar threats. Among the groups that have been threatened by the Black Eagles are the Colombian research institute Nuevo Arco Iris and the Washington Office for Latin America.

The appearance of the Black Eagles was accompanied by the appearance of dozens of other criminal gangs, generally involved in drug trafficking and selective assassinations. A study completed by Indepaz in 2006 identified 62 successor groups of the paramilitaries that had registered violent and criminal activities throughout the country, many of which had adopted names that were derived from the blocks of the AUC. It is possible that in some cases criminal gangs adopted the name “Black Eagles” in order to intimidate their victims into paying extortion or abandoning their properties. There is little evidence that the Black Eagles operate in a systematic manner as an integrated organization. To the contrary, it appears to be just a general name for the many successor groups that have adopted the tactics of the AUC and, in many cases, their political discourse.

Modus operandi

The upper level commanders of the Black Eagles are generally made up of demobilized paramilitaries – either those that opted out of the peace process with the government or those that were recruited by force. The lower level members of the groups appear to comprise recruits dedicated to drug trafficking for the most part. The Black Eagles have based themselves on the criminal networks that were established by the distinct paramilitary blocks throughout Colombia, but they have done this without adopting the same military structures and hierarchy. For the moment it appears that the different factions of the Black Eagles don´t have systematic relations with each other and they don´t appear to operate according to a federal criminal structure to coordinate their activities on a large scale. Moreover, they are not known for controlling international trafficking routes for the cocaine that is sent from the country.

The group usually announces its presence in a determined area by distributing pamphlets. Such pamphlets generally announce the imposition of a curfew during the night, declare war against any local gangs active in the area, or threaten the community with “social cleansing” (that is to say, threatening consumers of prohibited drugs, prostitutes, or “guerrilla sympathizers” such as trade union organizers or intellectuals). This is the same rhetoric that was once used by the AUC to impose strict social control within a determined area.

In Colombia, the Black Eagles have made their presence felt in areas that were crucial to the economic interests of the AUC. The fact that the first groups emerged in Catatumbo, North Santander and Nariño in 2006 is significant. These areas are some of the most densely planted areas where coca is grown and, ironically, they are also the areas where large numbers of demobilized paramilitary members reside. For the drug traffickers, the presence of coca in these territories made them too valuable to cede control over them to their rivals. After this first phase the Black Eagles then began to appear in the provinces where the major cocaine trafficking routes within the country are located such as the municipalities in the south of the province of Cordoba.

The emphasis of the group on protecting the corridors for transporting cocaine is accompanied by emphasis on maintaining the interests of the former paramilitary groups in land ownership and natural resource extraction. In places such as Cordoba, where some of the largest violent displacements of farmers and rural communities were perpetrated by the AUC, the Black Eagles have been accused of killing activists that were fighting for the restitution of lands acquired in this way. Similar threats have been made against activists and representatives of displaced people and communities in Santander. Armed groups calling themselves Black Eagles have been responsible for more recent forced displacements in Sucre, Choco and in the region of Uraba in Antioquia.

Following the approval of a law in 2011 that opened the way for the restitution of land to the victims of forced displacements and for the compensation of other victims of the armed conflict, there is a serious risk that the groups and individuals that have benefited economically from the conflict will contract the armed members of the Black Eagles to defend their ill-gotten gains. To the extent that Colombia continues selling off land for mineral exploration and extraction, petroleum and agribusiness on a massive scale, there is a high probability that the Black Eagles will be utilized to threaten any communities or groups that resist or protest against such projects.

SOURCE

* Las 2 orillas: Quienes son las Águilas Negras?, 10 September 2014

http://www.las2orillas.co/quienes-son-las-aguilas-negras/

“The continuity of para-militarism, fissures in the factions in power and peace”

By Jose Honorio Martinez, 5 April 2016

In the same way that the government of former president Alvaro Uribe Velez denied the existence of social conflict in Colombia the current government, according to the statements of the Minister for Defence Luis Carlos Villegas, denies the existence of para-militarism. Maybe para-militarism isn´t actively supported by the government of Juan Manuel Santos, but that doesn´t mean it doesn´t exist. Para-militarism has been a pillar of the dominant political regime in Colombia, the oligarchic State, since the 1960s. As Giraldo states in the official report of the Historic Commission on the conflict in Colombia and its victims (completed late in 2015):

“The counterinsurgency strategy of the State has been founded upon para-militarism. The official version of the phenomenon places its origin in the 1980s and explains it as arising from the reaction of rural land owners and agricultural and business associations to confront guerrilla actions, in response to which the land owners and businessmen in rural areas decided to create private armies to defend themselves, from which came the name commonly used to refer to such groups, “self-defence forces”. This remains the essence of the official version today. However, the real origin of para-militarism, as proven by official documents, can be traced back to the Yarborough Mission, an official mission to Colombia by officials of the Special Warfare College of Fort Bragg (North Carolina) in February 1962. The members of the commission left a secret document, accompanied by an ultra-secret annex, containing instructions for the formation of mixed groups of civilians and military personnel, trained in secret to be utilized in the event that the national security situation were to deteriorate…”

The formation of paramilitary forces was itself preceded by the creation of private militias at the service of large landowners in the late 1940s and early 1950s that ravaged the countryside during “the Violence” (a brutal civil war that claimed over 200,000 victims and displaced millions of people from rural areas)… The prolongation of the strategy of para-militarism over time and the role that it has played in the neoliberal era, violently displacing rural communities and taking over their land for agricultural, mining, energy and infrastructure mega-projects or to extend the domains of large cattle ranches, signified the construction of a para-State exercising dominion over large swathes of the territory, population and institutions of the country.

While it may well be that the paramilitary armies no longer receive orders directly from the government, that doesn´t mean that substantial sectors within the military establishment and other State institutions don´t still consider them to be allies in the fight against the counterinsurgents and therefore continue supporting them and maintaining the relationship of subordination. Considered in these terms, para-militarism isn´t just a group of criminal gangs that has infiltrated State institutions but rather represents a continuation of the armed elements of the para-State.

The ongoing assassination of human rights defenders, farmers and militants of the opposition (leaders and members of political parties and social movements opposing the traditional political parties and their offshoots) in the country denotes the maintenance of the same pattern of extermination practiced over the decades, at times varying in degree and intensity but always following the same methodology and objectives as outlined and implemented by the doctrine of National Security: anti-communism…

Giraldo describes the essence of this doctrine as follows: “In the arsenal of the doctrine of National Security, fundamentally comprising books (in the Library of the National Army), editorials and articles appearing in the Journal of the Armed Forces and in the Journal of the Army, discourses, presentations and reports of high level military commanders and their advisors, as well as in a collection of Counter-Insurgency Manuals marked as secret or confidential, “communists” are explicitly identified as trade unionists, farmers who don´t sympathize with or who are reluctant to cooperate with military operations on their farms, students that participate in street protests, militants of non-traditional or critical political forces, defenders of human rights, proponents of liberation theology, and sectors of the population generally that are not in conformity with the status quo…”

The recent shutdown imposed by paramilitaries in six provinces in the northwest of the country emphatically refutes the claims of the Minister for Defence that “there are no paramilitaries in the country today and we don´t want them to reappear.” In fact, para-militarism is not and has never been combated by the Colombian State. The supposed demobilization process carried out in 2005 pursuant to the “Law of Justice and Peace” formulated by the government of Alvaro Uribe was in fact the consolidation and modernization of the paramilitary project: legitimating the beneficiaries of the violent displacements of rural communities, laundering enormous amounts of money obtained from illegal economic activities, guaranteeing a substantial degree of impunity for the crimes committed and reinforcing the power of these elements of the para-State to continue activities such as extortion, imposing justice and controlling rural and urban communities, in one word governing the areas under their dominion.

The ways in which prominent personalities of the Establishment such as Fernando Londoño Hoyos … have campaigned against the peace dialogues being conducted in Havana Cuba and the manner in which the peace process has been the object of constant criticism by the most reactionary and retrograde political sectors of the country, has been accompanied by a systematic and meticulously planned campaign of assassinations of popular leaders throughout the “national territory”.

Para-militarism is a palpable truth of the oligarchic State in Colombia, prodigiously supported by substantial sectors of the dominant classes and landlords in particular. These same sectors of the ruling classes are now denouncing a campaign of political persecution being carried out against them by the government of Juan Manuel Santos, notwithstanding that they fully enjoy all of their civil rights as well as unconditional support by large parts of the mass media as demonstrated by the march that was held on 2 April 2016 during which participants carried placards and banners condemning the restitution of land to the victims of forced displacements, the prosecution of politicians and military officers allied to paramilitary groups, and the dialogues associated with the peace process more generally. For these factions within the traditional ruling classes whose interests revolve around the maintenance of the para-State the possible opening of a political regime that could result from the peace process constitutes a double threat: the first is that they perceive that the end of the armed conflict would abolish the most important basis for and justification of their lucrative economic activities, namely the fight against the insurgency; the second threat they perceive is that if the people that make up the armed insurgency are permitted to participate in the political processes on equal terms they will capture a significant portion of local and provincial political and administrative power.

The refusal of the government to recognize the continued existence of para-militarism and its connections to factions within the State is indicative of the equivocal nature of the liberal, progressive and modern sectors of the ruling classes when they are obliged to confront the retrogressive sectors dominated by the landlords and their associates. This situation has been a constant in Colombia´s history as demonstrated by the governments of Lopez Pumarejo and Lleras Restrepo when, instead of decisively supporting agrarian reform, they ceded to the pressure exerted by the landlords and the agricultural associations and ended up accompanying the processes of plunder and violence committed against farmers and entire rural communities and regions.

The lack of coherence within the progressive elements of the Colombian oligarchy and their unwillingness to commit themselves to taking the difficult but necessary steps if peace and social justice are to be achieved contrasts with the fanaticism and stubborn obsession of the reactionary elements of the oligarchy to keep the country in pre-modern political conditions. Today, in the midst of the crisis that the blind pursuit of policies of dependent capitalism has generated, the reactionary sectors of the oligarchy are agitating the banners of fear using slogans such as “Castro-Chavism” and urging the messianic restoration of former president Alvaro Uribe in order to guarantee the “legitimate defence” of the property of the landlords and the other beneficiaries of the violent displacement of millions of farmers and thousands of rural communities throughout Colombia.

Why don´t the progressive sectors of the Colombian oligarchy, or the sectors that present themselves as such, initiate the necessary fundamental democratic reforms corresponding to their role and status? The refusal to recognize the ongoing existence of para-militarism is equivalent to closing their eyes to an evident reality, a reality that was proven by the illegal intercepts carried out against their own communications by elements within the military/ intelligence apparatus during the election campaign of 2014. At the same time as they are lying to the country the progressive elements of the oligarchy are lying to themselves and facilitating the destruction of what remains of the oligarchic State by the elements committed to the preservation of the para-State.

The continued existence and strength of para-militarism pre-empts any possibility that the leftist political parties and social movements will be able to freely and fully exercise their political and civil rights, and it is for this reason that para-militarism must be eradicated as a pre-requisite for the construction of stable and enduring conditions of peace in Colombia.

SOURCE

* “La vigencia del paramilitarismo, las fisuras en el bloque de poder y la paz”, by José Honorio Martínez, Prensa Rural, Tuesday, 5 April 2016

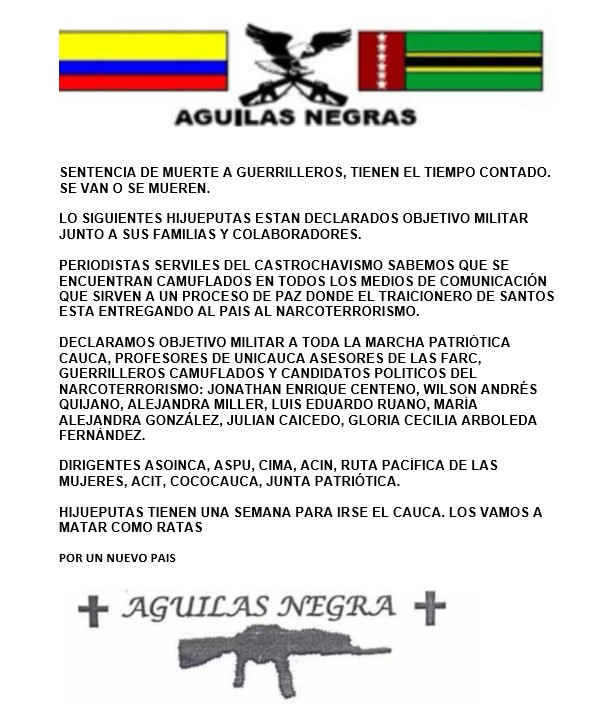

A copy of a death threat sent by the Black Eagles

The text reads:

A death sentence to guerrillas, you´re time is limited. Either go away or die.

The following sons of whores are declared to be military targets along with their families and collaborators.

Journalists serving Castro-Chavism we know that you are camouflaged in all of the means of communication that serve as agents of the peace process where the traitor Santos is delivering our country into the hands of the narco-terrorists.

We declare the following to be military targets: all members of the Patriotic March Cauca section, professors of the University of Cauca that serve as advisors to the FARC, and the following undercover FARC agents presenting themselves as political candidates on behalf of the narco-terrorists: … (seven people contesting the elections in Cauca at the time are identified).

Leaders of the social organizations ASOINCA, ASPU, CIMA, ACIN, RUTA PACIFICA DE LAS MUJERES, ACIT, COCOCAUCA, JUNTA PATRIOTICA

Sons of whores, you have one week to get out of Cauca. We are going to kill you like rats.

For a new country.

BLACK EAGLES