Originally appeared at Katehon

Final results from Iran’s February 26 elections show relative moderate President Hassan Rouhani and his allies winning a majority in the powerful Assembly of Experts and making a strong return to parliament as one of three dominant blocs.

The elections were Iran’s first since the international sanctions were lifted in connection with a landmark nuclear deal in July 2015, and reformist gains against hard-liners will almost certainly affect Tehran’s efforts to rebound from decades of political and economic isolation.

The strong showing by the reformist-and-moderate camp came despite intense vetting that moderates claimed had excluded many of their preferred candidates, and appeared to be most pronounced in the capital city Tehran.

President Rouhani and the controversial centrist ex-President Hashemi Rafsanjani easily won seats in the Assembly of Experts, the chamber of clerics that chooses and supervises Iran’s most powerful official, the supreme leader which has been occupied by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei during the past 27 years.

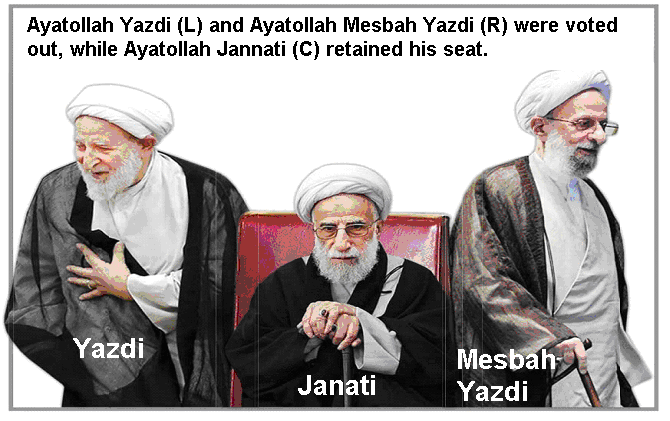

All-in-all, reformist-backed candidates claimed 52 of the 88 Assembly of Experts’ seats, according to the Interior Ministry, including 15 of 16 races in Tehran. In doing so, they managed to unseat several prominent conservative, including the current chief of the assembly, Ayatollah Mohammad Yazdi, and Ayatollah Mesbah-Yazdi.

But several prominent conservative were re-elected to the assembly, including Ayatollah Jannati, who narrowly clung to his seat. Ayatollah Jannati also heads the Guardians Council, the unelected, constitutional watchdog that disqualified hundreds of reformist candidates from the parliamentary and Assembly of Experts votes.

After the voting, the conservative head of Iran’s judiciary, Ayatollah Larijani, accused reformists of working with “American and English media outlets” to prevent conservatives from being reelected to the Assembly of Experts.

“Is this type of coordination with foreigners in order to push out these figures from the Assembly of Experts in the interests of the regime?” Larijani asked in a statement on February 29, referring to Yazdi’s and Mesbah-Yazdi’s election defeats.

During its next eight-year term, the assembly could name the successor to fiercely anti-Western Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who is 76 and has been in power since 1989.

Reformists had urged voters to cast ballots for a coalition of pro-reform and relative moderate candidates to prevent the re-election of hard-liners and conservative clerics.

On February 29, Iranian Interior Minister Rahmani Fazli announced a final combined turnout figure of 62 percent among Iran’s 55 million or so registered voters. This far out beats any turn-out rate in United States for example.

The parliamentary vote count and seat allocation was continuing. But none of Iran’s three main political camps – the moderates and reformists, the independents, or the conservatives and hard-liners – was expected to win an outright majority in the 290-seat parliament, known in Persian as the Majlis.

Still, the partial results so far indicate the best reformist and moderate showing in more than a decade.

President Rouhani and his reformist allies won all 30 of Tehran’s contested seats in the parliamentary vote.

Elsewhere in the country, the parliamentary results appeared to be split. Reports suggested as many as 50 seats had no clear winner and could require a second-round runoff vote in May.

Analysis

Unlike what some headlines in the Western press have described, this election was not a “win” for the reformists since they did not contest the election as reformists per se. They entered the election in an alliance consisting of reformists, centrists (described as Rouhani government supporters), and even some conservatives. This alliance explicitly introduced itself to the Iranian public as “the second step,”following the “first step” taken toward “moderation” in the 2013 election of President Hassan Rouhani. It also explicitly asked the electorate to vote for the complete lists of “Reformist and Government Supporters” (RSG), alternatively called the “Hope List”, as a way to remove from elected offices those who had publicly opposed the direction Pres. Rouhani had taken the country since his election.

The voters responded, particularly in the capital city of Tehran (more on this later), which has the largest number of parliamentary seats (30). They voted out some of the most vocal opponents of the nuclear agreement. This was possible since most, not all, of these MPs against the agreement were from the city of Tehran. It was also made possible because Tehranis seem to have voted in larger numbers than in the past couple of elections. As such the election could be better described as a referendum on the direction of the country under President Rouhani and whether the part of the population that supports the new direction could register its weight in a meaningful way despite a highly engineered electoral process.

A Divided Campaigning Strategy

The other side also managed to create a candidate list for the whole country based on alliance of several different factions that call themselves “principlist.” This alliance included members of the Islamic Coalition Party as well as an array of other conservative groupings that range from right of center to the ultra-conservatives such as the Steadfast Front. The criticism the organizers of the list faced was that the conservatives dominated their Tehran list and excluded some well-known conservative MPs who ended up producing their own competing list (which did not do well unless the names of the conservatives mentioned in their list also appeared on the RSG list). It also endangered some middle-of-the-road conservatives because of their association with the hardliners.

But the key point is that the principlists also worked predominantly through an alliance process. Their disappointing showing in Tehran should not deflect from the fact that their countrywide list has gained at least 25 percent of the seats in the parliament (even if within that list the conservatives did not do well). In fact, for those interested in Iranian politics, it is about time to talk less about Iranians moving in one direction or another sheep-like in droves and begin paying more attention to the political multiplicity embedded in the provincial politics of a socio-economically and culturally diverse country.

The RSG list did very well in Tehran and some provinces like Yazd and not well at all in some provinces such as South Khorasan. It has apparently done well in some big provincial cities such as Isfahan while not doing well in the rest of those provinces and vice versa. In Mashhad, the capital of Khorasan-eh Razavi, members of the principlist list swept all five seats (with at least one hardline opponent of the nuclear deal returning). Heavy vetting of reformist candidates and the lack of alternatives for the voters cannot be constituted as the sole explanation for this variation in results. Better organization, provincial networks, different issues, and so on must also be taken into account.

Despite these mixed results, the polarization of the elections between the two major alliances clarified the stakes in the election in terms of the policy direction of the country. At the same time, the mixed results better reflect the diverse sentiments in Iran. And this is what makes this election significant and interesting. Despite heated rhetoric, one side accusing the other of being the tool of outside forces and the other accusing the other of being extremist, the over-the-top language functioned as an instrument of persuasion in the competition for votes and not an instrument of elimination of the opponent from the competition. Even unelected authorities that have the power to eliminate only warned about foreign infiltration and called on voters to not vote for those whose ranks were infiltrated by the enemy or were following its dictates. Some voters were persuaded; others weren’t.

All-in-all, this heated and polarized rhetoric occurred within a healthy, calm, and collective environment, in the process confirming the elections as an established means for coalitions and alliances to compete against each other. This is an important step in the Iranian democracy, particularly after the contested 2009 elections and the heavily stacked 2012 parliamentary elections had thrown into question the integrity of the electoral process in Iran. To be sure, the 2013 election was the first step in re-establishing the integrity of elections within the frame of the Islamic Republic. But it was important to establish a trend and this election perfectly achieved that goal.

Coalition Building & Combined Electoral Lists

More than anything else, the two recent elections suggested that the time is over when one side thought it could get rid of the other side for good or even temporarily through force or manipulated electoral process, not that some sort of force majeure was not tried. The Guardian Council, dominated by clerics who themselves were candidates, did disqualify some rivals who could have won through their name recognition. However, this was in harmony with one of the conditions to be a candidate which is for one to believe in the tenants and principles of the Islamic Republic system.

However, in these disqualification cases, the opponents, instead of withdrawing or sulking, made the strategic decision to participate in an alliance that had proven successful in receiving 51 percent of the vote in the 2013 presidential election. And then they made the tactical decision to connect together, particularly in the city of Tehran, by repeatedly asking voters to support everyone on the so-called 30+16 lists (the first for the parliament and the second for the Assembly of Experts). This was tactically necessary because, in the case of RSG’s Tehran parliament list, only a few top names were known. The rest were unknown in terms of their names or points of view and had to be voted in blind based on who was on top of the list or who supported the list. The Assembly’s list also had unknown names, but problematically a few names were connected with dark parts of the Islamic Republic’s history (i.e. early post-revolutionary executions and the execution of some intellectuals and dissidents). So voters had to be convinced that voting for the whole list, while unsavory, was worth the elimination of others deemed more controversial.

By linking the two lists and coalition building, the issue became not only booting out hardliners who opposed Rouhani’s direction for the country but those who have relied on unfair instruments to eliminate electoral opponents. The use of this tactic almost cost the chief vetter, Guardian Council secretary Ayatollah Jannati, his seat in the Assembly of Experts (he ended up last out of the 16 seats available), and eliminated both Ayatollah Yazdi, the current chair of the Assembly, Ayatollah Mesbah Yazdi, the presumed spiritual leader of the conservative view that insists on the need for the Islamic part of the Islamic Republic to dominate over the republic part.

At any rate, the linking of the two lists and the call to vote for the entirety of this so-called “30+16 lists” was rather politically shrewd. But in order for it to work, individuals with social standing had to enter the fray and make the case for both blind voting. And many did, from university professors to well-known actors to famous athletes. Even political prisoners, including former presidential candidate and Green Movement leader Mir Hossein Mousavi and his spouse Zahra Rahnavard, let it be known that they would vote (a mobile polling station were taken to the Mousavi’s home where he is under house arrest) due to the raucous that he caused in 2009.

Mehdi Karroubi, the other presidential candidate under house arrest, also let it be known that he would vote, but for reasons that are not clear the mobile polling station did not reach his home until midnight. According to his spouse who reported on the interaction, he refused to vote that late, pointing to the illegality of voting after the deadline for poll closures had passed. Typical Karroubi, of course, this was another shrewd symbolic gesture made by a man who was also instrumental in 2009 disorderly behaviors that cast doubt on that presidential election which resulted in much chaos in the streets of Tehran as anarchists protested against the results.

I would be remiss if I did not mention one key politician, Former President Mohammad Khatami, who continued to play an outsized role for that part of the Iranian electorate that was still undecided about whether to vote or not. It is truly strange to claim a significant role for a man whose name isn’t to be mentioned and whose photo can’t be shown in the media (he is referred to in the press as merely the “head of the reform government”). But because of social networks, his widely seen and talked about video did what Former President Hashemi Rafsanjani, who headed a so-called “list of 16” for the Assembly excluding Jannati, Yazdi, and Mesbah Yazdi, could not do by explicitly stating the stakes and emphatically asking people to vote for everyone on their so-called “30+16 lists”.

Turnout in Tehran

Voters in north and central Tehran seem to have voted in higher numbers than in past few parliamentary elections. Although I am not yet convinced that voter turnout was higher throughout the country – preliminary results in fact suggest that it may have even been lower or the same in some provinces – the higher turnout in the city (not province) of Tehran is suggested by the higher number of votes received by top candidates.

In addition, the sequence of the votes read in various poll stations also suggests that some parts of Tehran voted more than others. In fact, in the first set of data released, Mr. Haddad Adel, a former speaker of the parliament on the principlist list, showed up seventh. But by the time votes in central and north Tehran began to be read he dropped to number 31 and never recovered. A similar dynamic was at play because the above three senior clerics, two of whom were eventually eliminated, began higher in the top 16 for the Assembly when votes from the smaller cities in Tehran province were read and gradually moved lower as more ballot boxes were read from more affluent parts of the city of Tehran.

This voting pattern is significant because the strength of the now defunct Green Movement – the anarchy movement that morphed out of the 2009 contested elected and that suffered a severe crackdown – lied in north and central Tehran. So the decision on the part of this segment of the electorate to vote in good numbers, in support of the country’s direction since Rouhani’s election, could be seen as a statement that “we exist and we intend to have our say in our country’s future.”

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei famously addressed this part of the population twice (the first time in the 2013 presidential election) by imploring them to come and vote even if they do not believe in either the Islamic Republic or him. The legitimacy of the Islamic Republic in the eyes of the world was at stake, he stated prior to this election, and that legitimacy is important in order for Iran’s enemies to give up their project of destabilizing Iran. This did not mean that he would support an electoral process that would allow candidates who clearly did not believe in the principles of the Islamic Republic to run easily. It also did not mean that he would stop warning voters against voting for candidates who were either fifth columns or were duped by the foreign enemy. But by linking the lack of legitimacy to the potential destabilization of Iran, he was making an obvious point that Tehran voters understood well given the horrendous instability and violence that has gripped many countries in the region, primarily Syria and before that Egypt, among many others.

But that understanding came with an expectation that, if they participated, their vote would be counted judiciously on Election Day. The enhanced legitimacy of the Islamic Republic of Iran in front of the world through the electoral process would necessarily have to involve domestic confidence in the integrity of the poll on Election Day and the institutional willingness to allow that poll to reflect adequately the varied political sentiments that reside in the complex and sophisticated Iranian society. This was a point well made in this election and apparently heard.