“My Lady Death, we beg you,

Please wait outside.’’

Russian song popular with soldiers at Stalingrad

Written by Dr. Leon Tressell. You may read the Part 1 HERE

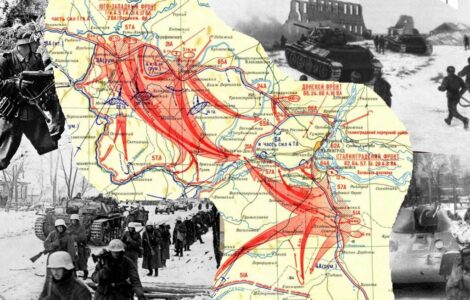

The encirclement and destruction of the German 6th Army 23 November 1942 to 2 February 1943

By mid November 1942 Hitler had to contend with defeat in North Africa at El Alamein, the Allied invasion of French North Africa, failure to capture the Caucasus oil fields and failure to capture Stalingrad. At this point Hitler had two choices. He could withdraw Army Groups A and B from the Caucasus and Stalingrad and prepare defensive positions for the winter. Aware of the Allied plans for an invasion of Western Europe, the long promised second front, Hitler decided he had to gamble on victory in Stalingrad hoping this would inflict a decisive blow to the Red Army.

Yet in Stalingrad itself the situation was extremely grim for Sixth Army Army. Richard Overy in his book, Russia’s War has observed that, “After two months of the most gruelling combat since Verdun the two sides had fought to a standstill. Neither possessed the means to defeat the other; neither could retreat.’’

Germany’s dictator and the high command in Berlin were completely unaware that the Red Army was secretly preparing a massive counter offensive, Operation Uranus, whose objective was to completely encircle an entire German field army for the first time. The Red Army would then move to destroy one of the Wehrmacht’s most experienced military formations. It was an audacious undertaking, which would involve the movement of hundreds of thousands of troops into position opposite Axis satellite troops on the north western and southern flanks of Sixth Army.

The planning for Operation Uranus required an ‘iron nerve’ as Stalin and his generals drip fed troops and supplies to maintain the precarious position of 62nd Army in Stalingrad. Meanwhile, they developed their plans for a new type of offensive which envisaged the broad envelopment of all Axis forces in the southern region of the USSR and the destruction of Army Group South. We should recall that during the summer and autumn of 1942 the Stavka launched over 8 separate offensives against the flanks of Army Group B which had all been costly failures.

These offensives, driven by Stalin’s desperation for a halt to the German advance towards the Volga, had different effects on Soviet and German thinking. The Stavka’s thinking, led by the Stalingrad Front commander General Eremenko, came to the conclusion that further assaults on the German flanks, in an effort to stop the Sixth Army assault on Stalingrad, were futile. A much broader envelopment of all Axis forces in Army Group B was needed that would strike against the weaker and poorly equipped Axis satellite troops from Italy, Hungary and Romania guarding the northern and southern flanks of Sixth Army.

Operation Uranus depended on several factors being fulfilled before the offensive could be launched. Firstly, the attritional battle in Stalingrad had to continue whittling down German strength while the Stavka devoted a much longer planning time for the preparation of the offensive. This was in sharp contrast to previous Soviet offensives which had been planned in a matter of hours and days.

Meanwhile, Hitler and his senior generals were complacent believing that the Wehrmacht, while under strength, could repel any future Soviet offensives against the flanks of Sixth Army. The ease with which Army Group B had repelled Red Army counter offensives during the summer/autumn of 1942 reinforced this German overconfidence in their abilities.

Having said this, it should be noted that some German commanders did at least recognise that their northern and southern flanks were exposed to a Soviet against against weaker and poorly armed Axis satellite troops.

From late September to mid November the Stavka thoroughly prepared the upcoming operation while elaborate secrecy measures ensured that German intelligence got no inkling of the massive forces being moved into place for the counter offensive. Over a million men were deployed in secret to their moving off points in the northern and southern pincers of the upcoming offensive. German intelligence believing that the Red Army had few reserves left had no inkling of this massive deployment. On the eve of the Soviet offensive General Zeitzler, Chief of the German General Staff, stated that, “the Russians no longer have any reserves worth mentioning and are not capable of launching a large scale offensive. In forming any appreciation of enemy intentions, this basic fact, must be fully taken into consideration.’’

German commanders at the front were just as ill informed as the general staff in Berlin about the upcoming offensive. When Operation Uranus began General Hoth, commander of the Fourth Panzer Army lamented, ‘We have overestimated the Russians at the front, but completely underestimated their reserves.’

Operation Uranus 19 November 1942 – the encirclement of Sixth Army

On Thursday 19 November at 7.20 am over 3,500 Red Army artillery guns, heavy mortars and Katyusha rockets started their bombardment of the northern flank of Army Group B along the Don river. This bombardment into a freezing thick mist was so intense it awoke men from the 30th Panzer division thirty miles to the south of the offensive. It was designed to blast a route for a dozen infantry divisions, three tank corps and two cavalry corps.

After an hour the bombardment shifted forward to the Romanian second line and Red Army infantry advanced towards Romanian trenches. Lacking heavy weapons, especially anti tank weapons the Romanians repulsed several waves of infantry attacks but buckled once tanks were sent en mass against them.

By midday the 4th Tank Corps and 3rd Cavalry Corps had smashed through the Romanian IV Corps on the Kletskaya sector. Thirty miles to the west the 5th Tank Army pulverized the defences of the Romanian II Corps with its flanks protected by the 8th Cavalry Corps.

To compound matters the Romanians and their German allies didn’t receive any air support from the Luftwaffe due to snow and thick icy mists.

As Red Army tanks and cavalry raced south steering by compass due to the freezing mist the head of Sixth Army failed to respond. Anthony Beevor in his account of the battle exclaims,’Having failed to do organize a mechanical strike force before the enemy offensive, he [General Paulus] continued to do nothing.’’

By 5pm 4th Tank Corps had advanced over 20 miles through a heavy blizzard. At this point Army Group B took action and ordered General Strecker’s XI Corps to form a line of defence to protect the rear of Sixth Army.

Wehrmacht commanders hindered by lack of information from the front still believed this was a local offensive similar in size and intent to the Red Army offensives of the summer/early autumn. They had no idea that Soviet forces were attempting a complete encirclement of Sixth Army which would be comprised of two parts, an inner ring and outer ring to make doubly sure that Sixth Army would not succeed in any break out attempt.

At 10pm on 17 November, seventeen hours after the start of the Red Army offensive, General Weichs, commander of Army Group B, ordered all offensive actions in Stalingrad to be halted. Panzer and motorised units were ordered west to secure the lines of communication/supply of Sixth Army and its left rear flank.

Chuikov’s 62nd Army made this disengagement as difficult as possible by launching strong attacks on German tank and motorised units.

As panzer and motorised units slowly made their way west the southern flank of Sixth Army was left vulnerable to attack. At 10am on 19 November Soviet artillery launched a 45 minute bombardment of German and Romanian lines on Sixth Army’s southern flank.

The Soviet 13th Mechanized Corps led the advance supported by 64th and 57th armies south to Beketovka. Soviet tanks smashed through the lightly armed Romanian lines. Meanwhile, twenty five miles to the south the 4th Mechanized Corps and 4th Cavalry Corps led the 51st Army into the attack.

Red Army soldiers going into the attack displayed high spirits. Their enthusiasm stemmed from a desire for revenge against a genocidal enemy who showed no mercy to Soviet soldiers and civilians alike. Vasily Grossman a Red Army journalist and author of the epic novel of the battle Life And Fate, advanced alongside the infantry. He recalls:

“The faces of Red Army soldiers have become bronze red from the severe winter winds. It isn’t an easy fight in this kind of weather, to spend long winter nights out in the steppe under this icy wind that penetrates everywhere, yet the men are matching cheerfully. This is the Stalingrad advance. The army is in exceptionally high spirits.’’

By 21 November the northern pincer of the Soviet offensive had collapsed the Romanian defences leading to over 27,000 of them becoming prisoners. On the southern front there was an equally dramatic collapse of poorly equipped Romanian forces many of whom displayed ‘tank fright’ and surrendered in large numbers.

Thousands of Romanian soldiers who tried to surrender were shot out of hand by angry Red Army soldiers who were furious at the way the Romanians had treated the local population. Vasily Grossman walked with advancing troops on the southern front and describes his entry into the village of Abganerovo in his article, ‘On the Roads of the Advance’:

“An old peasant woman told us about the three months of occupation. ‘It became empty here. Not a single hen to cackle, not a single cock to sing. There isn’t a single cow left … Romanians have pinched everything. They whipped almost all our old men. … They took away my son, a cripple, and with him a girl and a nine year old boy. We’ve been crying for four days, waiting for them to return.’’

Grossman describes how captured Romanian soldiers were searched before being sent off to the rear, ‘Heaps of peasant women’s belongings that were found in rucksacks and pockets of Romanians looked comic and pitiful.’

Meanwhile, a ‘catastrophic fuel situation’ hampered the movement of panzer and motorized divisions westwards as they attempted to form a new defensive front to protect Sixth Army’s supply lines. The Red Army’s war of movement left the Wehrmacht floundering with German infantry divisions being forced to abandon their artillery as they turned their attention west to the northern pincer of the Red Army.

As Soviet spearheads in the north and south pressed forward into the rear of Romanian units Paulus and his commanders remained ignorant of the objective of the Red Army offensive.

Within four days of the offensive the two Red Army pincers met up on the Don river some sixty miles west of Stalingrad. The first ever encirclement of a German field army was sealed when Soviet units from the north and south met at the village of Sovetsky, a few miles south of Kalach.

Richard Overy describes the catastrophic situation facing the Wehrmacht in the following terms:

“The German southern front was in disarray. Men, horses and guns lay in grotesque frozen heaps where they fell. The Red Army cleared the steppe around them, until a corridor over a hundred miles wide separated the German front from Paulus, the 6th Army and remnants of the 4th Panzer Army, a total of 333,000 men.’’

By the end of November 1942 the Red Army had torn a 250 kilometre hole in the German front. General Paulus headquartered at Gumrak airfield, 15 kilometres west of Stalingrad, organised Sixth Amy into five sectors to defend the pocket from the inner ring of the Red Army’s encirclement. Each German division faced 3 to 6 Soviet divisions.

German relief attempts at rescuing and supplying the 6th Army pocket

Field Marshal Manstein, commander of Army Group Don, was given the almost impossible task of organising a counter attack which would end the encirclement of Sixth Army and save it from destruction. Manstein decided upon an attack from the south giving the relief operation the code name Winter Tempest.

According to some historians Manstein’s plan for the offensive worked on the assumption that once the relief force approached Stalingrad then Hitler would relent and permit part of Sixth Army to break out and link up with the approaching panzer forces.

We should recall that Hitler had insisted that Sixth Amy stand fast once it was encircled. He believed the fatally flawed assurances given by Goring and General Jeschonnek that the Luftwaffe would be able to fully supply Sixth Army which would enable it to hold on until it was relieved by Manstein’s counter attack. The false promises they made to Hitler would have required at least 1050 ju-52s to deliver the estimated 750 tonnes of supplies required every day to keep Sixth Army alive. Yet the Luftwaffe had only 750 of these planes available and a third of these had been used to airlift German troops to Tunisia in response to the Allied landings in French North Africa.

Having said this, we should recall that Hitler was also influenced by Manstein’s assurance that a relief operation was possible. Glantz and House in their single volume history of the battle have noted how Manstein’s fateful assurance left Sixth Army condemned to inaction. They explain:

“Manstein broke the nearly unanimous assessment by Weichs, Paulus, and other German generals that an immediate breakout was the best if not the only solution to the threat posed by the Uranus encirclement. Manstein’s self confidence helped eliminate this option, committing Sixth Army to wait for external relief. Manstein’s arguments confirmed Hitler’s natural tendencies, encouraging the dictator to believe that even if the Luftwaffe were unable to resupply the pocket completely, it could provide sufficient help to allow Sixth Army to hold on long enough.’’

Subsequent events would prove these assumptions to be fatally wrong and would condemn Sixth Army to destruction.

A week into the siege of Sixth Army a mere 200 planes were mustered to start the airlift. This rose to 300 planes a week later which was still woefully insufficient. Glantz and House have observed that the airlift delivered about 117.6 tonnes of supplies a day to Sixth Army. The failure of the airlift led to a drastic reduction in rations for the men of Sixth Army to starvation levels. On 26 November rations were reduced from 2,500 calories a day to 1,500 calories a day. This was further reduced to 1,000 calories a day on 8 December. It was clear that Sixth Army would perish by starvation rather than enemy action unless something was done to relieve it.

Everything now depended on the success of the relief operation to save Paulus and his men.

The Stavka had plans codename Operation Saturn to push Axis forces out of the eastern Donbass region and trap Army Group A in the Caucasus. The unexpectedly large size of the trapped German forces at Stalingrad and the upcoming relief attempt by the Wehrmacht led Stalin and his commanders to scale down Operation Saturn to Little Saturn. They were however taken by surprise to hear that General Kirchener’s LVII Panzer Corps had launched its relief attack on 12 December earlier than expected. The 2nd Guards Army was despatched to block the German relief effort.

Meanwhile, the 5th Tank Army was directed to conduct an offensive along the Chir river to secure the eastern flank of the developing Operation Little Saturn. This week long offensive successfully prevented any attempts by XXXXIII Panzer Corps to relieve Sixth Army from the west. Several units such as the 7th Tank Corps were now available to help block LVII Panzer Corps counter attack in the south from Kotel’nikovo.

Operation Winter Tempest 12 December

The German relief effort which began at 0430 on 12 December was a woefully understrength force comprising 240 tanks and assault guns which set off from Kotel’nikovo. It started off by successfully smashing the centre and right wing of 51st Army’s defences and routed several Soviet divisions. By 13 December the 13th Panzer Division had seized crossings across the Askai river.

Alarmed by this Stalin sent the 2nd Guards Army to block LVII Panzer Corps further advance. From 14-18 December a savage struggle was fought on both sides of the Askai river as each side launched attacks and counter attacks for control of crossings over the river. The weakened state of German panzer divisions is illustrated by the conversation between the commander of the 17th Panzer Division and General Hoth. The commander of the 17th Panzer Division complained to the commander of the Fourth Panzer Army that his division had only 30 tanks and many of his panzer grenadiers had no trucks to transport them into battle. General Hoth replied, ‘At the front some divisions are in an even worse state. Yours has an excellent reputation. I rely on you.’

By 19 December General Kirchener’s panzer corps had reached the Myshkova river. Soviet forces had taken heavy casualties as they retreated but they had absorbed the limited combat power of LVII Panzer Corps reducing it to less than a hundred operational tanks.

Recognizing this Manstein sent a report on 19 December to Berlin stating that his forces could not achieve victory on their own, they needed Sixth Army to do its part and attempt a break out from its encirclement. On the evening of the same day Manstein sent a radio message to Paulus pleading with him to commence a break out and advance 20 kilometres to the Donskaia river.

Paulus and his chief of staff, Major General Schmidt, rejected Manstein’s demand stating that Sixth Army lacked both mobility and ammunition to achieve such a break out.

There has been considerable debate amongst historians as to why Paulus refused to order a break out by Sixth Army. Many portray him as a defeatist who lacked sufficient strength of character to disobey Hitler’s order to stand fast in Stalingrad.

In defence of Paulus some have noted that Sixth Army had grave shortages of fuel, ammunition and horses to transport heavy weaponry. Any break out would have had to accomplished on foot leaving behind both the wounded and heavy weaponry.

In response to this one could reply that Paulus knew how the air lift was failing and how his men were fighting under constantly reducing rations while having to use twice the normal amount of ammunition. His armies ability to fight effectively was being severely reduced every day yet he failed to take action to initiate a break out.

Events to the south of Stalingrad would soon make this issue a moot point as LVII Panzer Corps ran into the 2nd Guards Army.

Conditions for troops on both sides were very difficult and pushed men to the limits of their endurance. A history of the Soviet 24th Rifle Division states:

“There was no vegetation, water, or lodgings in the region but, on the other hand, it abounded in dry gullies and ravines. Supplying water and heat to the units and especially the medical points represented a particularly difficult problem. The temperatures approached up to -42 degrees. The soldiers were in sheepskin coats, felt boots and jackets and caps with ear flaps but the cold gripped the men. Movement was only possible by crawling on all fours.’’

During the third week of December Sixth Army’s hope of relief by LVII Panzer Corps died as the latter was not only blocked but driven back to its starting point by 2nd Guards Army.

The climax of Operation Winter Tempest came during the period 19-24 December where LVII Panzer Corps, with a meagre 16,000 troops, engaged with 2nd Tank Army which numbered over 100,000 men. By 23 December it had been driven back to the Askai river. On Christmas Eve a massive force consisting of 149,000 men, 635 tanks and 1,728 guns and 294 combat aircraft smashed into LVII Panzer Corps which was forced to retreat amid heavy casualties. Soviet forces brushed aside German defences. By 29 December 2nd Guards Army had captured Kotel’nikovo from which LVII Panzer had started its relief offensive towards Stalingrad.

As if this was not bad enough the Stavka launched Operation Little Saturn on 16 December which led to the encirclement and destruction of the Italian Eight Army. Soviet forces rapidly advanced against poorly equipped Italian forces and under strength German units and caused havoc in the rear of Army Group Don. By the evening of December 22 Manstein concluded that stopping the Red Army’s Operation Little Saturn was vital to prevent the capture of of crucial airfields south of Donets. Hitler reluctantly agreed that the relief attempt towards Stalingrad would be stripped of vital units such as the 6th Panzer Division which was diverted to the north. This left LVII Panzer Corps on the Myshkova river with only 19 tanks to face the 2nd Guards Army.

By Christmas Eve Soviet spearheads were 200 kilometres into the rear of Army Group B. The principal Ju-52 airfield at Tatsinskaia was overrun and there was no airlift to Stalingrad that day.

By the end of December 1942 Operation Winter Tempest had been totally defeated and the whole of the southern front of the Wehrmacht had collapsed due to the successful Little Saturn offensive. Army Group Don was focused on extricating Army Group A from the Caucasus. Reluctant to admit that Sixth Army was doomed to destruction Hitler issued a new Fuhrer directive on 27 December which stated that “the liberation of Sixth Army’’ remained the central goal of the Wehrmacht in southern Russia.

Sixth Army encircled in the Volga kessel

As Manstein’s relief effort came to a grinding halt and then was forced to retreat beyond its starting off point the position of Sixth Army went from bad to worse. By 16 December it had only 25,000 combat infantry compared to 40,000 on 21 November. Yet it faced seven Soviet armies including the depleted 62nd Army.

Most of its divisions were immobile due to the shortage of horses, this problem grew worse as the few remaining horses were killed to feed the troops.

Staff officers from Sixth Army HQ estimated that only one division, the 29th Motorised Infantry Division, was capable of offensive tasks while only the 60th Motorised Division and 371st Infantry Division were fully qualified for defensive tasks.

Sixth Army’s armoured strength had fallen to a paltry 103 functioning tanks which were dispersed in small groups to help different sectors of the pocket fend off Soviet tank attacks.

Throughout December units from all seven armies continually launched small scale probing attacks which Sixth Army was able to fend off at great cost in casualties. Stalingrad Front commander Eremenko moved additional divisions to the south of the pocket to ensure that any attempted breakout would face overwhelming opposition. The Red Air Force also intensified air strikes against German units on the German positions in the south of the pocket. These combined actions ensured that Paulus would not attempt any breakout.

In Stalingrad itself the bitter attritional fighting continued against a backdrop of growing demoralisation of German troops. A mood which even penetrated Paulus’s headquarters according to Glantz and House. Chuikov directed his troops to numerous attacks in late December in an effort to expand the Soviet bridgehead on the west bank of the Volga. This would enable more troops to be accommodated for the upcoming Operation Ring which was designed to crush the pocket in January 1943.

During this period small storm troops of Red Army soldiers recaptured various German strongholds along the Volga river. General Rodimtsev’s 13th Guards Division took the House of Railway Workers, the L-Shaped House and the House of Specialists while other units began the reconquest of the Mamaev Kurgan.

Under the blows of these relentless attacks the rate of casualties for Sixth Army was such that it caused a bottleneck in evacuating the wounded by air. This was finally resolved in early January 1943 when 1,200 seriously wounded were evacuated by plane.

On 26 December Paulus radioed a bleak assessment of Sixth Army’s position to Manstein:

“Bloody losses, the cold, and inadequate supplies have recently made serious inroads on the combat strength of the divisions. For that reason I must report:

- The army is weaker than in the past to repulse enemy attacks and clean up local crises. The prerequisite remains better supply and speedier influx of replacements.

- If the Russians withdraw stronger forces from Hoth and employ these or other troops to launch mass assault on the fortress, we cannot resist this for long.

- Donnerschlag will no longer be feasible if a corridor is not punched through beforehand and if the army is not replenished with men and supplies.

I therefore ask you to make representations to the highest level to ensure energetic measures be taken for the rapid link up with the army. If not you will force the sacrifice of the entire force.

The army will do everything to hold out to the last.’’

In response to Paulus both Hitler and Manstein continued to offer false hope, in other words lie, about the possibility of relief when it was patently clear that the Wehrmacht just did not have the forces to launch another effort to relieve Sixth Army.

On 1 January 1943 Hitler sent the following disingenuous message to Paulus, ‘Every man of the Sixth Army can start the new year with the absolute conviction that the Fuhrer will not leave his heroic soldiers on the Volga in the lurch and that Germany can and will find a means to relieve them.’

Hitler and his general staff were prepared to sacrifice Sixth Army as it tied own large numbers of Soviet forces giving the Wehrmacht time to stabilise its shattered lines on the southern front and rescue formations such as Army Group A from destruction in the Caucasus.

Meanwhile, the Stavka was putting the final touches to Operation Ring which would complete the destruction of an entire German field army for the first time in the war.

Central to the concept of this offensive was the crushing use of massive amounts of artillery to destroy Sixth Army’s defences before sending in tanks and infantry against the pulverized German infantry.

The initial Soviet plan greatly underestimated the size of German forces in the pocket and envisaged a three stage attack lasting seven days in total. By early January the offensive was changed again and the direction of initial attacks were changed so that they would chop the pocket up into digestible parts. Thus the attack would beginning by loping off the extreme western and eastern lobes of the pocket.

Operation Ring was to be accompanied by several other Soviet offensives designed to capture Rostov and trap Army Group A in the Caucasus as well as attacks designed to roll back Axis forces from the middle reaches of the Don river.

Calm Before the Storm and German War Crimes

By the end of December 1942 many soldiers in Sixth Army became consumed with hunger as aerial resupply by the Luftwaffe was grossly inadequate with only 158 tonnes being delivered each day which was barely sufficient to keep the army alive never mind keep it equipped with fuel and ammunition. The daily ration consisted of 80g of bread a day which was occasionally topped up with some horse meat.

The following extract from the diary of Field Gendarmerie Sergeant Helmut Megenburg illustrates this well:

“… Yesterday we got vodka. At that time we actually cut up a dog, and the vodka really came in handy. Hetti, I have already cut up four dogs, yet my comrades can’t eat their fill. One day I shot a magpie and cooked it.. . .”

Having said this, rations for the men of 62nd Army were no better with the daily bread ration amounting to 100g a day.

Conditions for German troops were bad yet they paled in comparison to those suffered by Red Army prisoners of war kept at camps at Voroponovo and Gumrak inside the pocket. At these camps 3,500 Soviet prisoners of war were left to starve to death, dying at a rate of twenty a day on the grounds that this meant ‘taking food from German soldiers.’ Desperate Russian prisoners resorted to cannibalism and still nothing was done to improve their conditions. By the time Stalingrad was liberated only twenty Red Army men were left from the original 3,500 prisoners.

Anthony Beevor in his book Stalingrad recalls that at the end of the battle Red Army soldiers were horrified by what they discovered at the two camps where their comrades had been held prisoner:

- “The spectacle which greeted the Russian soldiers … was at least as bad as those seen when the first Nazi death camps were reached. At Gumrak, Erich Weinert, [a German communist working with Red Army intelligence], described the scene: ‘In a gully, we found a large heap of corpses of Russian prisoners, almost all without clothes, as thin as skeletons.’ The scenes, particularly those of the ‘Kriegsgefangen-Revier’ filmed at Voropvono, may have done much to harden the hearts of the Red Army towards the newly defeated.’’

As the Red Army moved its armies into position for the upcoming offensive, which was put back to 10 January 1943, Paulus was making hasty preparations for the coming battle. Heavy combat casualties forced him to ‘retrain’ support personnel to fight as infantrymen. Using such measures he managed to maintain Sixth Army’s combat strength at around 25,000 men. The weary commander of Sixth Army directed Colonel Lattman of the 14th Panzer Division to coordinate the construction of multiple fall back defensive positions throughout the different sectors of the pocket. On the eve of the Soviet offensive Sixth Army had 102 functioning tanks, lack of fuel led some tanks to be dug in into the frozen ground as virtual pillboxes, and 22 assault guns.

Arrayed against Sixth Army were the three Soviet assault armies under General Rokossovsky had a combat strength of 212,000 men, supported by 7,949 artillery guns and mortars and 400 combat aircraft. In the main attack sectors Soviet forces had an 8 to 1 advantage in manpower, 5 to 1 in armour and 20 to 1 in artillery. Numerous engineer units were sent to reinforce Rokossovky’s front and were engaged in obstacle clearance, road construction, camouflage and deception measures including dummy equipment and communications.

Glantz and House in their account of the battle have observed, “The Soviet advantage, on top of the half starved condition of the German troops and Voronov’s [tasked to plan Operation Ring by the Stavka] careful planning, made the destruction of Sixth Army inevitable.’’

Operation Ring and the annihilation of Sixth Army

On the 8 January General Rokossovsky sent his personal representative to deliver surrender terms to Paulus. These included full POW status which protected German soldiers from the threat of summary execution which was major fear of many, food, and medical care of wounded soldiers. Any commander who genuinely cared for the welfare of his men when faced with such a hopeless situation would have surrendered and saved the lives of his men. Paulus was not such a commander and he rejected the surrender terms out of hand. He was intent on following Hitler’s orders that Sixth Army should fight to the last man.

In the ensuing battle Paulus again rejected Soviet surrender terms (on 18 January 1943) when his men were being decimated by the Red Army offensive. Paulus’s refusal cannot just be put down to the moral failings of a man who had steadfastly followed his Fuhrer’s orders. Geoffrey Roberts in his book Victory At Stalingrad has explained Paulus’s refusal to surrender from the point of view of Paulus’s adherence to Nazi ideology:

“As Bernd Wegner has commented, there was more to Paulus’s obstinate refusal to surrender than a warped sense of military honour and discipline. It represented the extent to which he and other commanders had embraced Nazi fanaticism and internalised the ‘crusading character of the “anti-Bolshevik’’ war’.’’

Even at the end of the battle when Red Army troops had captured his headquarters Paulus refused to order his men to lay down their arms. It was left to junior officers to agree to a de facto capitulation.

In the wake of this refusal to surrender the Red Army proceeded with its offensive which began in the morning of 10 January 1943. The attack began with an intense artillery barrage of over 7,000 field guns, mortars and rocket launchers which lasted fifty five minutes. Colonel Ignatov, a Red Army artillery commander noted the intensity of the bombardment, ‘There are only two ways to escape from an onslaught of this character – either death or insanity.’

The Soviets then launched their attacks on the west, southern and north eastern fronts of the pocket. Within twenty four hours the German strong points at Marinovka and Karpovka in the west of the pocket had been captured. As Red Army soldiers advanced peasant women rushed to the shattered German trenches looking for blankets and anything of value for their needs. The German communist Erich Weinert, who accompanied the advancing soldiers later described the terrible carnage and chaos of destroyed equipment at this section of the front:

“Karpovka looks like an enormous jumble sale. The dead are lying, grotesquely twisted, their mouths and eyes still open wide with horror, frozen stiff, with their skulls torn open and their bowels hurled out, most of them with bandages on their hands and feet, still soaked with yellow anti-frostbite ointment.’’

By the 15 January Soviet spearheads had crossed the Rossoshka river and pursued German units east towards Stalingrad. Amidst the carnage many German units, that were still capable of defensive actions, had to resort to building up snow banks as defensive barriers on the open steppe as there was not time to dig trenches into the frozen ground. There were growing reports of German soldiers succumbing to ‘tank fright’ as the massed ranks of Soviet armour pressed forward against Wehrmacht units with no means of resisting them

Entire German divisions disappeared under the ferocious Soviet attacks. By 15 January Sixth Army had lost 60,000 troops killed, wounded or captured. Having said this, it must be noted the Red Army suffered heavy casualties as it faced fanatical resistance from many German units. In the first three days of the offensive it lost over 26,000 men. Many German soldiers up to the last retained a fervent belief in the Nazi cause. One non commissioned officer reflected:

“I have now taken over a heavy anti-tank gun and organized eight men, four Russian [Hiwi] among them. The nine of us drag the canon from one place to another. Every time we change position, a burning tank remains on the field. The number has grown to eight already, and we intend to make it a dozen. However, I only have three rounds left…during the night I cry without control like a child.’’

Meanwhile, a Luftwaffe sergeant wrote home:

“I am proud to number myself among the defenders of Stalingrad. Come what may, when it is time for me to die, I will have had the satisfaction of having taken part at the most eastern point of the great defensive battle on the Volga for my homeland, and given my life for our Fuhrer and for the freedom of our nation.’’

On 16 January Sixth Army lost its main airfield at Pitomnik as the retreat of German forces became increasingly chaotic. The German supply position became catastrophic with supplies falling to less than ten tonnes a day from that day on. Large numbers of wounded were left to fend for themselves due to the shortage of fuel for trucks with many freezing to death in the open.

Vassily Grossman whom accompanied the advancing Soviet troops noted the terrible conditions for men on both sides of the battle:

“It is severely cold. Snow and the freezing air ice up your nostrils. Your teeth ache. There are frozen Germans, their bodies undamaged, along the road we follow. It wasn’t us who killed them. The cold did. They have bad boots and bad coats. Their tunics are thin and look like paper … There are all over the snow. They tell us how the Germans withdrew from the villages along the roads, and from the roads into the ravines, throwing their arm s away.’’

Not surprisingly, a growing number of German units surrendered. On the 16 January a whole battalion surrendered for the first time in the battle.

Paulus was forced to move his headquarters back into the city as General Rokossovsky ordered a four day pause for his troops to rest and refit for the final assault on the pocket. On 17 January Rokossovsky renewed his offer of surrender terms which was again rejected out of hand by both Hitler and Paulus.

By this point many German soldiers had had enough and the prospect of dying a glorious death for the fatherland held little appeal. Corporal Josef Schwartz told his Soviet captors, “… I read an ultimatum, and burning anger at our generals boiled up in me. They apparently decided to finally kill us in this damn place. Let the generals and officers fight themselves. Enough for me. I am fed up with the war…”

Soviet leaflets promising German soldiers that they would be well treated if they surrendered, began to resonate with men at the end of their tether. Captain Kurt Mandelhiem told his Red Army interrogator:

“… In our battalion, in the last two days alone, we lost 60 people killed, wounded and frostbitten, more than 30 people ran away, there was only ammunition left until the evening, the soldiers did not eat at all for three days, many of them have frostbitten legs. Before us was the question: what to do? On the morning of January 10, we read a leaflet containing an ultimatum. This could not but influence our decision We decided to surrender in order to save the lives of our soldiers…”

It should be noted that during Operation Ring the Red Army launched several devastating offensives on other fronts giving Hitler and Manstein more urgent problems than the slow death of Sixth Army. Hitler and Manstein saw the continued resistance of Sixth Army as necessary to absorb a huge amount of Soviet combat power while the Wehrmacht desperately tried to stabilise its collapsing southern front.

On 13 January the South-western and Voronezh Fronts started their offensive on the Don river and rapidly encircled the Hungarian Second Army and the Italian Alpine Corps. Soviet troops tore a 160 kilometre gap in the Axis front south of Voronezh. The dire situation facing the Wehrmacht in Southern Russia got even worse when the Briansk and Voronzeh Fronts attacked the German Second Army forcing it retreat in disarray towards Kursk and Belgograd.

The Red Army’s final advance and the annihilation of Sixth Army

The final stage of Operation Ring began officially on 22 January. However, on 21 January the 24th, 65th and 21st Armies began a reconnaissance in force against the north western corner of Sixth Army’s defences. The reconnaissance by the 24th and 65th Armies was so successful that Rokossovsky ordered them to simply continue their advance. Meanwhile, on 22 January after a 70 minute artillery barrage the 21st, 57th and 64th Armies resumed their offensive and faced “stubborn enemy resistance’’ and so they made slow progress on the first day of their final offensive. The 371st Infantry Division slowed down the Soviet advance towards Gumrak airport which came within range of Red Army artillery.

Starvation drove many German soldiers to surrender in large groups. General Christiakov, commander of the Soviet 21st Army claimed he saw a field kitchen advancing in front of the riflemen of his 293rd Division which led to many German soldiers surrendering to the field kitchen in order to be fed.

On the same day that the Soviet offensive rendered Gumrak airstrip inoperable Hitler messaged Paulus telling him that surrender was out of the question, ‘Capitulation is out of the question. The troops will defend themselves to the last.’ Paulus responded to this order with a fanatical display of loyalty to the genocidal dictator. From the comfort of his bunker he sent the following suicidal message to his soldiers, ‘Hold on! If we cling together as sworn community and if everyone has the fanatical will to resist to the utmost, not to be taken prisoner under any circumstances, but to persevere and be victorious, we shall succeed.’

By the end of the second day of the offensive Soviet units came within 4 kilometres of the southern suburbs of the city. On the 24 January the pocket collapsed by one third in size as the inexorable advance of the Red Army forced Sixth Army units to retreat into the western suburbs of the city. Many German divisions abandoned or lost their heavy weapons as they were forced to retreat deeper into the city.

German surrenders gathered pace. On 25 January Major General Moritz von Drebber, commander of the 297th Infantry Division, surrendered his headquarters to the 57th Army’s 38th Rifle Division. On the same day, Field Marshall Manstein issued a gag order to all German officers of Army Groups B and Don that forbid all discussion, ‘for what had happened to the Stalingrad pocket.’ In sharp contrast to this Stalin issued an order to the entire Red Army congratulating his soldiers on their great achievements over the previous two months.

On 26 January General Rokossovsky launched a Red Army’s offensive to cut Sixth Army into two pockets. The disorganised, exhausted, malnourished German defenders were extremely short of ammunition of all types and in not much of a condition to resist the last offensive directed against them.

The 52nd Guards Division of 51st Army rapidly broke through the defences of the Wehrmacht’s 44th and 76th Infantry Divisions leading to a link up between the guards division and units from 62nd Army near the upper Krasnyi Octiabr village. Despite this rapid advance other Soviet armies continued to face fanatical resistance from several shattered units of Sixth Army. Some German commanders managed to keep their diminished units together as coherent fighting forces. The 65th Army slowly advanced toward the factory villages near the Krasnyi Octiabr factory due to the surprisingly strong resistance from XIV Panzer Corps.

Many German units disintegrated with large groups of leaderless men seeking shelter from the never ending stream of artillery and air strikes. Meanwhile, other units surrendered once their ammunition had run out. The 64th Army captured 15,000 German soldiers who had surrendered between 27 and 29 January.

You would have expected any general who genuinely care about his troops to issue an order to surrender in this situation where continued resistance was completely futile. Yet Paulus under fire made several trips out of his headquarters to different locations urging his commanders to continue resistance and avoid a formal surrender.

From the 27 January onwards the Stavka began to withdraw certain divisions from Stalingrad so they could rest and refit in preparation for upcoming offensives. Rokossovsky earned the reputation as an “unbloody general’’ as he insisted on the need to preserve infantry manpower by saturating German defences with artillery and tank fire. This had the effect of slowing the Soviet advance somewhat.

By 28 January the German wounded and sick were receiving no rations and left to starve as the few supplies that were parachuted into the pocket were rarely recovered.

Large groups of German soldiers began to surrender especially in the southern pocket. In many cases commanders led the surrender to stop the carnage. On 29 January Lieutenant General Daniels surrendered the 3,000 surviving members of the 376th Infantry Division. On the same day Brigadier General Dumitriu surrendered the remnants of his 20th Romanian Division to spare his men from a katiusha bombardment.

By this point General Strecker had taken command of Sixth Army forces in the northern German pocket while Paulus commanded the rapidly shrinking southern pocket.

In the northern pocket three Soviet armies faced desperate resistance from the 24th Panzer Division and the 389th Infantry Division. There were unable to eject German forces from the Barrikady and bread factories.

By 30 January the southern pocket had collapsed and the headquarters of Paulus were surrounded. Hitler promoted Paulus to Field Marshall in the hope that the commander of Sixth Army would commit suicide since no German field marshal had ever surrendered. On the morning of 31 January Colonel Adam, an adjutant of the newly created field marshal, left Sixth Army headquarters and surrendered unconditionally to Major General Laskin of the 64th Army. Following this a host of German generals surrendered that day in the southern pocket to Soviet forces. Over 50,000 Axis soldiers went into Soviet captivity that day.

Incredibly, Paulus refused to instruct the northern pocket to surrender claiming he neither communications nor the authority to do so now that he was captured. It was clear that this fanatical Nazi still believed in the futility of continued resistance.

Rokossovsky anxious to save the lives of both German and Soviet soldiers ordered the commanders of 65th and 66th Armies to limit their troops actions to reconnaissance on 31 January. He reasoned that the defat of the southern pocket together with a lack of supplies would lead to further surrenders. It is worth noting that only 62nd Army continued offensive actions and persisted with the house to house fighting it had been engaged in for the last five months.

In the face of the refusal of the northern pocket to surrender General Rokossovsky ordered a massive artillery bombardment by three Soviet armies on the morning of 1 February. Together with massive air strikes by the Red Air force this led to a rapid collapse of the northern pocket. Incredibly, on this last day of fighting there was no let up in the ferocity of the combat between German units and the forces of Chuikov’s 62nd Army. Krylov, chief of staff of 62nd Army later noted that on 1 February only 116 Germans surrendered to 62nd Army while it lost another 42 killed and 105 wounded.

On 1 February as his soldiers were being destroyed Hitler radioed an order to the northern pocket demanding the defenders fight to the last man. In reply XI Corps sent a message warning: “Resistance is expected to come to an end on 2 February as a result of overwhelming superiority and the expenditure of all ammunition.’’ Meanwhile, isolated pockets of German resistance remained in the centre of the city despite the surrender of the southern pocket.

During the night of 1-2 February General Streicher rejected several requests from his subordinates to surrender. At 7am on 2 February he relented and ordered all units in the northern pocket to lay down their arms. Streicher surrendered to 66th Army and 40,000 German soldiers went into captivity. At midday the 62nd Army sent Combat Report No.32 to the Don Front headquarters, “The troops of 62nd Army have completely fulfilled the combat mission at 12,00 hours on 2 February 1943.’’

Aftermath

As the guns fell silent many were disorientated by the peace and quiet. Lieutenant Anatoly Mereshko recalls:

“The sudden silence was overwhelming, and some of our soldiers, habituated to the constant din of fighting, couldn’t stand it. The only time there was silence during the battle was just before an enemy attack. Men were shooting rifles, letting off grenades, just to let off tension.’’

Despite overwhelming firepower Soviet casualties for Operation Ring amounted to 48,000 men in the face of fanatical resistance from shattered German units who often fought to the last round of ammunition.

Estimates of German and allied losses during Operation Ring vary. Glantz and House note that on 9 January just prior to the Soviet offensive Sixth Army had a ration strength of 212,000 to 217,000 men. Of these only 91,000 survived to go into captivity.

Civilian casualties are difficult to establish. When the Sixth Army arrived at Stalingrad in August 1942 the city had a population of roughly 400,000 people. In early February 1943 the NKVD found 7,655 surviving civilians. It is estimated that the Germans took between 185,000 to 187,000 civilians at gunpoint to work as slave labourers in German factories. Meanwhile, at least 75,000 civilians died during the Luftwaffe bombing of the city in September 1942.

On the afternoon of 2 February 1943 a vast crowd of German prisoners were marched down to the Volga. Soviet commanders and soldiers alike knew that the Germans had drawn up plans for a victory march on the banks of the Volga after the city had been conquered. The German prisoners were lined up in military order while Red Army men gathered to watch. There was a momentary silence before the order to ‘March!’ was given to the soldiers of Sixth Army. Private Mark Slavin of the 45th Division recalls what happened next:

“Then all our soldiers began to sing. We sang Russian songs which helped to sustain us when all had seemed hopeless. I took out my notebook … I was intending to write a short piece for our divisional newspaper. But I couldn’t describe the scene before me. Instead, I found myself writing one sentence, again and again: “Glorious Stalingrad is free!.’’

Conclusion

The original plan of Operation Blau, the second summer offensive of the Wehrmacht in the Soviet Union was simple: seize the oil fields of the Caucasus. This would obtain essential fuel supplies for the German war machine and deny this to the Soviet Union. It is quite clear that once Hitler added the extra mission of capturing Stalingrad then the chances for success for the whole offensive fell to zero. Under strength Army Groups A and B were expected to travel vast distances over rough terrain against an enemy who showed incredible resilience. The hubris of the German High Command led them to consistently underestimate the ability of the Red Army to generate new infantry and armoured divisions.

Hitler and his senior commanders allowed themselves to be drawn into an attritional warfare in Stalingrad for which the Wehrmacht was ill quipped. Its Blitzkrieg tactics were of no use in the grinding urban warfare that was the battleground in Stalingrad. In their desperation to take the city Hitler and his senior commanders took greater and greater risks leaving their long extended flanks along the Don river to be defended by poorly equipped Axis allies. When the Soviet counter blow came in the form of Operation Uranus it was devastating and tore a gigantic hole in the German southern front from which it would never recover. After its encirclement it was only matter of time before Sixth Army was annihilated.

Lieutenant- General Alexander Von Daniel, commander of the 376th German Infantry Division gave the following estimation to his captors about the calamitous impact of the Wehrmacht’s defeat at Stalingrad:

“… The operation to encircle and liquidate the 6th German Army is a masterpiece of strategy. The defeat of the German troops at Stalingrad will have a great influence on the further course of the war. To make up for the colossal losses in people, equipment and military materials suffered by the German armed forces as a result of the death of the 6th Army, huge efforts and a lot of time will be required…”

This defeat of German fascism came at a terrible cost for the Red Army. Soviet armies from the start of Operation Blau to the German surrender on 2 February 1943 suffered approximately 1.7 million casualties of whom 850,000 died. This colossal sacrifice was not in vain. As Anthony Beevor has pointed out the men of the Red Army had inflicted, ‘the most catastrophic defeat hitherto experienced in German history.’

By early November German and allied forces had suffered over 250,000 casualties. From early November to the final surrender in February 1943 Glantz and House agree with Soviet estimates that German and allied forces lost over 800,000 men. Of these 580,000 had been killed, wounded, missing or evacuated by airlift from Stalingrad. We then need to add around 220,000 prisoners of war of whom 91,000 surrendered at Stalingrad. Only 5,000 men from those that surrendered in Stalingrad returned to Germany many years after the war.

These figures do not do justice to the severity of the defeat suffered by German fascism during the battle for Stalingrad. The Wehrmacht suffered the destruction of two of its most experienced armies: the Sixth Army and Fourth Panzer Army along with the loss of four allied armies: the Romanian Third and Fourth Armies, the Italian Eighth Army and the Hungarian Second Army. All told the Wehrmacht had lost over a million men which it could not replace. Following the defeat at Stalingrad only Romania continued to supply significant forces to support Wehrmacht operations.

Stalingrad represented a decisive turning point in the Second World War and dealt a devastating blow from which the Wehrmacht was unable to recover. As Glantz and House have concluded it, ‘established that Germany could not win on any terms.’

At Stalingrad the Red Army had brought the seemingly invincible German Wehrmacht, which had conquered most of continental Europe, to its knees. Historian John Erickson provides a fitting verdict on the achievement of the Red Army in defeating German fascism at Stalingrad, ‘the impossible, the unthinkable and unimaginable happened on the Eastern Front.’

Suggested Reading:

Anthony Beevor, Stalingrad

Alan Clarke, Barbarossa

Artem Drabkin , Red Army Infantrymen Remember the Great Patriotic War: A Collection of Interviews with 16 Soviet WW-2 Veterans

David Glantz and Jonathan House, Stalingrad

Vasily Grossman, Life and Fate

Vasily Grossman, A Writer At War with the Red Army 1941-1945

Michael Jones, Stalingrad: How The Red Army Triumphed

Richard Overy, Russia’s War

Victor Nekrasov, Front-Line Stalingrad

Geoffrey Roberts, Victory At Stalingrad

Letters from German soldiers who fought At Stalingrad can be found at:

Letters from the Battle of Stalingrad

Epic battle,here is a lesson from history for the Ukrainian Nazis and the Nato criminals.

One really misses this type of encircle tactic, used a lot by the soviet union, now in the Ukraine war.

”At 10pm on 17 November, seventeen hours after the start of the Red Army offensive, General Weichs, commander of Army Group B, ordered all offensive actions in Stalingrad to be halted.”

It must be a typo : At 10pm not on 17, but on 19 November.

”At 10am on 19 November Soviet artillery launched a 45 minute bombardment of German and Romanian lines on Sixth Army’s southern flank.”

Again, it must be a typo : At 10am not on 19, but on 20 November.

It is an excellent work, easy to read, understand and remember..

Thank you !

Thank you for pointing out the typos. I could do with a proof reader.

All you have heard about WWII is a lie.

Germany was never defeated, the Nazis were just fighting a fifth dimensional warfare up to this day to get all communist crawling out from under our beds, and now the final battle, the Endlösung, will be fought finally against all Commies and the ordinary joos.

You sound like you need to start taking your medication again!