Written by Daniel Edgar exclusively for SouthFront

There has been a surge in deadly cartel-related clashes, massacres and other gruesome atrocities in Mexico during the months of January and February as the territorial and sectorial disputes between several of the cartels have intensified. Meanwhile, in the midst of the devastation wrought by the ongoing violence and the social and economic disruption caused by the pandemic, the country prepares for crucial mid-term elections which will take place in June.

Many of the deadly clashes and other incidents that have occurred are the result of an intensification in the longstanding turf wars between rival cartels and other illegal armed groups in several northern regions and cities as they seek to expand their influence and control over strategic territories, resources and public and private sector institutions.

Among the cartels most heavily involved are the Sinaloa Cartel, Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación, Cartel del Noreste (Cartel of the North-East) and Cartel del Golfo (Gulf Cartel). They have also been involved in intermittent heavy clashes with the public security forces and more frequent but less intensive clashes, ambushes and confrontations in many parts of the country.

Other violent incidents instigated by the cartels and other criminal groups have had the objective of eliminating perceived political threats or rivals, or have been related to constant efforts to forge or impose political allegiances, obedience and alliances in the lead-up to the nation-wide mid-term elections (for the National Chamber of Deputies – the lower house of the National Congress – and for the governors of 15 states, as well as for many state and local assemblies, and mayors of most municipalities in the country).

In terms of the multiple confrontations taking place between cartels and other organized crime groups and State authorities and security forces, there have also been several high profile cases involving the exposure of deep-seated collaboration between certain State authorities and security officials and illegal armed groups, most notably in the State of Tamaulipas following the massacre of 19 immigrants in January.

In the southern parts of the country, rural and remote farming and Indigenous communities continue to be besieged by heavily-armed paramilitary forces. While many of the illegal armed groups appear to belong to cartels operating in the region, reports from many of the communities affected suggest that in at least some cases the illegal armed groups’ actions also appear to serve the interests of the proponents and beneficiaries of the numerous major natural resource and infrastructure developments projects that are being imposed by external interests and actors throughout the region, whether directly or indirectly.

The latest spike in turf wars, confrontations and wanton violence – and related developments in the national government’s efforts to reduce the capacity and influence of the cartels and identify and target their core structures, personnel and activities (as well as the diverse forms of collaboration that they have formed with certain State and market-based institutions and personnel) – reiterate the importance of continually reevaluating and reinforcing the ongoing processes of institutional reform and integrated strategies to combat organized crime groups of all types, taking into account the multitude of institutional and social factors and circumstances that have contributed to the explosion of violence and corruption along with the drastic deterioration of living conditions that have overwhelmed the country during the last two decades.

Territorial disputes and armed clashes between cartels

In terms of the ongoing clashes between the cartels and other illegal armed groups, several underlying factors have had a strong impact on recent developments. The rivalry between the Sinaloa Cartel and Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG) remains one of the most determinant factors driving the course of many of the ongoing turf wars throughout the country, manifesting in a large number of different localities and contexts throughout the country in varying degrees of intensity according to the local and regional alignment of forces and conditions (including the presence and relative strength of the cartels and other illegal armed groups in each area, the strategic importance of the territory and its place in the geographic deployment of each group’s forces and their strategic and operational objectives). Developments in each area are also affected by the ability of State institutions, civil society organizations and communities generally to resist and confront the incursions of the illegal armed groups and their collaborators – or, conversely, the extent to which key institutions and social sectors have been infiltrated by or are actively collaborating with the cartels.

According to recent reports and analysis, the deadly disputes between the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG to control the strategic territories and transport corridors along the US border and in adjacent regions is going through a period of escalation, with each group making an all-out effort to eliminate, take over or absorb the other cartels and criminal groups in the relevant areas. LINK1, LINK2

At the same time, there has been a series of clashes and atrocities in adjacent regions of major strategic importance to northern transport corridors (particularly Nuevo León and Tamaulipas), in this instance primarily involving clashes between the other two cartels which have a significant presence in the region, the Cartel del Noreste (CDN) and Cartel del Golfo (CDG).

It appears that the latest efforts of the two dominant cartels to impose their authority once and for all over their less powerful rivals (notwithstanding substantial differences in the prevailing balance of forces and firepower in specific localities) has been facilitated by the numerous operational successes of State authorities over the last six months or so, which have resulted in the capture or extrajudicial killing of the leaders or other senior members in the structures of several smaller cartels and crime groups, reducing their leadership and cohesion and leaving them more vulnerable in terms of the incessant multi-dimensional turf wars and factional disputes in which they are immersed.

In this context, there have been numerous reports of local and regional alliances (or betrayals) occurring between the two dominant groups and other cartels and their multiple factions and networks in specific regions and localities including Tijuana, Zacatecas and Ciudad Juarez. (See, for example, HERE, and HERE)

The information and psychological war between the various groups and factions has undergone a corresponding escalation, with each faction trying to outdo the other(s) in terms of the perpetration of horrific atrocities in order to unnerve their rivals and pump out triumphalist claims concerning the imminent eradication of their enemies’ forces.

In this context, there have been numerous videos and images spread (primarily by social media) of mutilated victims allegedly belonging to one faction or another, and it appears that the CJNG has been subjected to several significant tactical defeats in this respect which have been trumpeted and amplified by concerted propaganda campaigns. There have been repeated claims by its rivals that the cartel has overextended itself and cannot arm and protect its members, associates and collaborators. Only time will tell if this is indeed the case or not.

Although overall the CJNG has been the principal objective of Mexican law enforcement and security forces investigations and combat operations over the course of the last year after a series of ambushes and attacks that it carried out against senior State officials, and it is also the cartel that has been most affected by the efforts of Mexican financial investigators and regulatory authorities over the last two years to identify and neutralize cartels funds and accounts, it still seems somewhat improbable that the group’s ability to obtain weapons and other pre-requisites to protect its territories and members could have been affected to the degree suggested by its rivals. Moreover, there are also contradictory reports claiming that the CJNG has launched a ‘winter offensive’ in several key regions which has had a considerable degree of success in displacing, taking over or eliminating rival groups notwithstanding some localized setbacks.

In either case, if the CJNG manages to antagonize its rivals sufficiently they could feasibly put aside their differences long enough to form a combined front to annihilate the cartel, which together with the emphasis placed on combatting the cartel by the Mexican government and security forces would constitute an existential threat to the CJNG.

The dramatic events in the northern state of Tamaulipas earlier this year, including the massacre of 19 immigrants in January and the subsequent exposure of collaboration between the CDN and a variety of State officials and members of the public security forces (discussed in more detail below), have also brought the full weight of the law (and wrath of the national government) on the CDN and its networks of collaborators and is likely to greatly weaken if not eliminate the cartel as such. Another likely contributing factor to the determination of the national government to obliterate the cartel is the reported attempt by some of the group’s members to shoot down a military helicopter earlier this month.

Nonetheless, while the recent incidents in Tamaulipas and adjacent areas have been particularly dramatic and traumatic, they are not likely to be of major long-term significance in and of themselves as what remains of the CDN’s resources, personnel and fragmented structures and cells will, almost inevitably, promptly be absorbed or taken over by the other cartels in the region and a new ‘equilibrium’ will eventuate depending on whether one of the remaining cartels manages to defeat or dominate the others or whether a new stalemate in the long-running war of attrition is reached.

Unless, the consolidated efforts of the authorities to eradicate the CDN can be carried over into ensuring other groups do not move in to fill the temporary void, and some breathing space can be secured to provide a solid basis for rebuilding and consolidating the heavily abused and degraded State institutions in the region and healing the shell-shocked and traumatized communities and social sectors.

Clashes between the cartels and public security forces

As mentioned above, the CDN (Cartel del Noreste) reportedly tried to shoot down a military helicopter in the northern State of Nuevo León earlier in February after the helicopter located and approached one of its paramilitary encampments. According to media reports the attempt failed, and the helicopter’s crew called in ground reinforcements which rapidly arrived and killed at least five of the illegal armed groups gunmen, capturing four others. LINK

Previously, in November of last year the CDN killed a municipal police chief and two of his senior aides in the same region (in the state of Nuevo León, adjacent to the State of Tamaulipas), which is located on a strategic transport corridor that is currently the subject of a fierce conflict and frequent armed confrontations between heavily armed groups affiliated to the CDN and Cartel del Golfo (CDG).

There have been numerous other clashes with and ambushes of public security forces in several regions over the last few weeks. LINK

Tamaulipas the latest focus of national and international attention

The massacre committed on the 22nd of January this year in Camargo (in the State of Tamaulipas), when 19 people – most of them immigrants from Guatemala – were murdered and their bodies incinerated inside two vehicles, brought a deluge of attention to the long-standing allegations of embedded collaboration between State officials and at least one of the cartels active in the region (the CDN).

As soon as the identity of most of the victims of the massacre was determined, the Guatemalan government demanded that the ‘full weight of the law’ be brought against those responsible. Guatemala’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs subsequently announced that Guatemalan authorities are working on a daily basis with their Mexican counterparts, and acknowledged the efforts of Mexican officials and their active cooperation and support in the investigation of the case.

The Mexican government is equally determined to identify and neutralize the perpetrators, and twelve members of the Tamaulipas State Police have already been arrested for their alleged involvement in the crime. Most recently (on Wednesday 24 February), the national Prosecutor-General announced that the office is also preparing a dossier that will be forwarded to the National Congress seeking the removal of the governor of Tamaulipas from office on a series of charges that include collaborating with organized crime groups in the region.

On repeated occasions and from a variety of sources officials of the Tamaulipas State Police and its commando unit, the Special Operations Group (Grupo de Operaciones Especiales, GOPES), have been accused of actively collaborating with cartels and other criminal factions present in the region in a campaign of terror being waged against local residents and other civilians in Tamaulipas, including many cases that have been denounced to State officials involving the detention and kidnapping of residents by police officers who have then handed the victims over to cartel members to be interrogated, tortured and murdered, either seeking ransoms or in order to spread terror among the communities and entrench their control over the territory, and also to dissuade people against denouncing abuses of authority and demanding investigations of the links between local security forces and other public officials with the illegal armed groups that are operating in the region.

In the aftermath of the massacre of the Central American immigrants in January, relatives of several local residents who have allegedly been kidnapped and disappeared by the Tamaulipas State Police travelled to Mexico City to denounce the crimes and try to get the responsible authorities to prioritize the series of related cases. According to media reports, the Human Rights Commission in Tamaulipas (CODHET) received 91 complaints involving arbitrary detentions and forced disappearances in the course of 2019, and although the figures for 2020 have not been officially announced they are likely to be in a similar range.

One such incident that has been reported in the media occurred in January, when State police officers detained four people in Mier municipality after the vehicle they were travelling in was intercepted by the police. The victims were taken to a police facility in the adjacent municipality of Miguel Aleman before being handed over to suspected Gulf Cartel (Cartel del Golfo, CDG) members.

Citing local media reports, Borderland Beat reported:

“The case sent shockwaves through the community in Ciudad Mier and prompted multiple protests…

The kidnapping in question occurred on 6 January 2021, when members of the Tamaulipas State Police mounted an operation in Mier municipality and arrested four individuals: Luis Alberto Herrera Avalos, Jaime Santacruz, Mario Alexis García Bocanegra and Brian Eduardo García Bocanegra.

All of them were taken to the nearest transit police office in Miguel Aleman, about a 20-minute drive from where they were arrested. At the time when the four were in police custody, their families began to receive calls threatening calls requesting them to pay a ransom…

One of the victims told reporters that the head of the transit police, Monico Garza, met with suspected cartel members inside the police headquarters.

“The police chief [then] left the building and in less than two minutes a man carrying an AK-47 came in…”

The abductees explained that the man who was supposed to take them began to doubt himself. Apparently, he was told that there were two abductees, not four. Confused, the man left the building through a secondary door. Two of the victims, the Bocanegra siblings, were released…

While the Bocanegra siblings were able to see their family again, the relatives of Luis Alberto and Jaime received videos where their loved ones were being tortured [and they have since disappeared]…” LINK

In another case, a former Tamaulipas State Police officer has been imprisoned by Federal authorities and is being investigated following allegations he provided confidential information on police activities to members of the Northeast Cartel (CDN) and recruited several colleagues on their behalf. He is also accused of collaborating in the murder of several other state police officers who either refused to cooperate with the CDN or were suspected of collaborating with the CDG.

As noted above, Federal prosecutors have announced that 12 police officers of the Tamaulipas State Police have been arrested for allegedly assisting the Northeast Cartel (CDN) in the massacre of 19 immigrants, including by giving false testimony and tampering with evidence at the crime scene in an attempt to mislead the investigation, among other indications of collusion between the police and cartel members in the months preceding the incident. All the officers have been charged with homicide, abuse of authority, abuse of administrative duties, and for providing false testimony to authorities.

Three of the 12 police officers arrested had previously received training from the US Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL). The program they were part of consisted of “basic skills and/or first line supervisor [human rights] training” between 2016 and 2017. LINK

The strategic significance of ongoing processes of institutional recuperation

There have been numerous successes in the pursuit of high profile corruption cases and multiple arrests (or extra-judicial killings) of senior and mid-level commanders from several of the major cartels operating throughout the country over the last year. Nonetheless, if the institutional reforms and operational strategies for combatting crime and corruption are to have a long-term impact that makes it much more difficult for corrupt practices and abuses of power of all types to evade detection and prosecution, one aspect of utmost urgency is expanding the institutional authority and substantially augmenting the operational capacity of all accountability mechanisms and agencies throughout the federalized system of government.

In particular, all components of the nation-wide human rights and anti-corruption systems must be strongly supported and reinforced, without prejudice to the other fundamental accountability agencies at all levels of the system of government – such as the Office of the Public Prosecutor, the Office of the Auditor-General, and corresponding super-intendencies and other regulatory officials responsible for ensuring legality and propriety in the functioning of financial, corporate and property markets and registries of all types. The organizational structures and operational objectives and strategies of all such entities must be consolidated and integrated in a mutually supportive framework of coordination and cooperation within the overall supervisory and control functions of the Presidency and Congress (and corresponding supreme executive and legislative entities at the state and municipal levels).

As noted in a previous South Front report, while the high degree of centralization of decision-making and accountability that has been favoured by the national government over the last two years facilitates operational control and fast decision-making in a dangerous and rapidly changing environment, and can make infiltration and subversion by corrupt or hostile elements more difficult, it also has several inherent drawbacks and disadvantages. One of these is that a consequence of the centralization of most major command, control and accountability functions and powers is that the structures and officials involved are further removed from and more inaccessible to the people they are meant to protect, serve and belong to.

Another disadvantage of the centralized approach that has been favoured by the national government and legislators in the security and anti-corruption spheres is that it risks sidelining, weakening and ultimately rendering largely irrelevant other key accountability agencies and authorities both at the national as well as at the state, municipal and autonomous community levels (including but not limited to those officers and agencies mentioned above).

Many of the agencies affected by the centralization of key powers and functions are responsible for activities that are just as crucial in combatting the diverse forms of collaboration between the cartels and other organized crime groups and State officials dispersed throughout much of the State apparatus at all levels as well as corresponding private sector institutions – from law enforcement and other security forces to apparently mundane but equally imperative tasks such as maintaining land registry systems and the administration of other official documents, the financial sector and other market sectors and commodities and securities exchanges, to landlords, companies involved in major agribusiness and resource development projects, and other traditional or recently emerged local and regional economic elites (who may be inclined to collaborate with illegal armed groups and other organized crime networks, whether voluntarily or through compulsion).

The centralized and hierarchical structures have also tended to limit or exclude the participation of many of the civil society organizations and social sectors most affected by specific decisions and activities, preventing them from contributing to official efforts with their often vast professional knowledge and practical experience in related fields.

In terms of the organization, deployment and field operations of the public security forces, one aspect that merits extensive public analysis and debate is the establishment of community police and, given the scale and firepower of the illegal armed groups in many areas, well-armed community militia forces, integrated with rapid reaction forces from the conventional public security forces so that they can call in immediate support in the event of major confrontations.

This is an extremely delicate matter that would require the most careful planning, execution and oversight, but it is also a matter of fundamental importance. In many countries in Central and South America non-conventional local and regional paramilitary formations have been formed, often with devastating consequences for local communities as they have generally been the target of such formations which have operated on behalf of powerful landlords and a variety of economic and political elites and subject to their command, control and oversight, rather than being the result of genuine community-based decision-making, participation and oversight. The ‘Convivir’ program in Colombia of the 1990s which became the platform for the proliferation of many predatory and bloodthirsty paramilitary groups is one case in point.

Numerous remote Indigenous communities in Mexico (mostly in the south of the country) have already taken the step of creating armed community militias in order to be able to defend themselves – to some extent at least – from marauding cartels and other illegal armed groups. However, such initiatives continue to face strong resistance from the conventional authorities, and the community-based security forces that have been established are generally heavily outgunned by the illegal armed groups.

In terms of ongoing and future processes of institutional recuperation and consolidation, as the recent developments in Tamaulipas emphatically demonstrate – where a multitude of State police officers and now the Governor’s office are finally being investigated after years of denunciations to the state’s Human Rights Commissions (in the case of the former) – the network of Human Rights Commissions throughout the country is a fundamental component of the institutional arrangements being developed to confront all forms of corruption, abuse of State power and other criminal activities.

However, as is very often the case at a time when the budgets of state and municipal jurisdictions are being substantially reduced, the Human Rights Commissions are almost universally severely under-resourced and do not receive anywhere near enough support and cooperation from other, more highly prioritized and much better equipped and resourced, agencies that have been hardwired into the national anti-corruption and anti-organized crime offensives. The same applies to other key accountability and control agencies and officers, particularly at the state and municipal level but also in some instances at the national level.

More specifically in this instance, unless the Tamaulipas Human Rights Commission receives the unconditional support and cooperation of other State authorities and officials from all levels, not only will the Commission continue to find it impossible to advance its many outstanding investigations, but its members and staff will be left exposed to obstruction, blackmail and extortion by corrupt and complicit (or simply anxious and fearful) officials, and face the additional risk of horrific acts of retribution by the illegal armed groups and organized crime networks that are terrorizing the region.

Many other agencies of accountability and control are responsible for equally vital and complementary roles (such as the Offices of the Public Prosecutor and Auditor-General, the Land Titles Offices and corporate registries, Notaries, and securities and exchange officials, etc.), which in many instances receive crucial support and information from civil society organizations and professional associations which often have more elaborate and long-standing relations with local communities and other vulnerable and disadvantaged social sectors.

The previous report by South Front considered the national anti-corruption system that has been elaborated over the last five years in considerable detail. The nation-wide network of citizen’s participation committees and related structures and civil society organizations of which the anti-corruption system is comprised generally face the same structural and operating challenges as their counterparts in the Human Rights Commissions; a severe shortage of professional and technological capacity and operating resources, greatly exacerbated by a chronic situation of at best benign neglect by successive state and Federal governments and legislatures. The failure of the anti-corruption measures that have been adopted in the southern State of Oaxaca to produce any tangible results up to now is a case in point. LINK

Reinforcing the status and capacity of both the Human Rights Commissions and Citizen Participation Committees and their related structures in the National Anti-Corruption System (as well as civil society organizations operating in related fields) will be crucial if the efforts to greatly reduce and if possible eliminate the most severe forms of abuse of power, corruption, organized crime and endemic violence throughout the country are to be successful in the long-term.

The proponents of, participants in and financial sponsors and beneficiaries of major resource-development projects also merit close attention in this regard, most emphatically when they are being implemented in areas infested by illegal armed groups that are terrorizing local communities and civil society organizations perceived as constituting obstacles to project management and territorial control, wealth accumulation and other manifestations of ‘economic development’ and ‘progress’.

If there is to be any prospect of a relatively harmonious and constructive resolution to the numerous outstanding social and environmental disputes and conflicts throughout the country, all such resource development and infrastructure projects must be subjected to comprehensive ‘best practice’ environmental and social assessment impact studies from projection inception to termination and rehabilitation of affected areas, including detailed cost-benefit analysis (incorporating ‘triple bottom line’ economic, social and environmental parameters) that takes into account at least the following scenarios: (1) if the project is imposed on the region by external actors (the national government and corporations) despite the strong opposition and objections of many of the communities affected, (2) if the project proceeds with the free and informed consent of communities affected, (3) alternative project parameters designed to reduce adverse social and environmental impacts, and (4) possible alternative development paths that could be pursued. In this context, particular attention must be given to an in depth investigation of all illegal armed groups and other organized crime networks active in the affected region or otherwise appropriating the financial flows and other resources generated by the projects (including – perhaps above all – their ‘white collar’ counterparts associated with major project developments in the major urban and financial centres who shroud their predatory practices and massive wealth accumulation in dubious but iron-clad claims of commercial confidentiality and ‘the national interest’).

This has been one of the major weaknesses of all progressive ‘socialism for the twenty-first century’ governments throughout Latin America since the emergence of the first of them in Venezuela in the late 1990s with the election of Hugo Chavez to the presidency (with the possible exception of Bolivia, where the Indigenous peoples constitute a majority of the population).

Under heavy pressure to modernize and expand industrial, agricultural and infrastructure development projects and rapidly improve the living conditions of the huge numbers of people living in poverty, they have all remained trapped in a twentieth century paradigm in terms of the emphasis placed on massive and hugely environmentally destructive resource extraction projects which generate large revenue streams for the national budget (and make a much more modest contribution to employment generation) in the short term but, with very few exceptions, have devastating consequences for most of the members of the communities living in areas affected by the projects.

The recent history of Ecuador clearly demonstrates this phenomenon and the adverse consequences it has had on the ability of progressive groups and sectors of society to unite in the pursuit of shared objectives and values: during its approximately ten years in power the government of Rafael Correa did as much as almost any government in the region to lift the majority of its people out of poverty, and expand and improve industrial capacity, economic development and the national infrastructure and social services. However, it relied heavily on massive natural resource development projects to underpin and finance its ambitious development strategy without prioritizing measures to reduce adverse environmental and social impacts, and further resorted to repressive measures to impose the projects upon the communities living in areas affected by projects.

This caused widespread resentment and mistrust within the country’s well-organized and quite powerful Indigenous movements, which is capable of determining around 20% of the vote in national elections and has on numerous occasions convened mass mobilizations, strikes and blockades that have brought the country to a halt (most recently in late 2019). Whether this rift between Ecuador’s Indigenous movements and the political party and presidential candidate contending to be Rafael Correa’s successor (Andres Arauz of the UNES political party) in the fiercely contested and polarized national presidential election to be held in April will have a major impact on the course of future political developments. In this instance, there are (at least) three major poles around which the major social and political forces are converging which in extremely simplified and homogenized terms can be reduced approximately to; progressive socialism (and national liberation from US hegemony), traditional neo-liberalism (and absolute conformity and compliance with the Washington consensus), and Indigenous environmentalism and community-based development (although the Indigenous movement’s presidential candidate in the first round held in early February, Yaku Perez, had a distinctly ambiguous policy platform in geopolitical and national economic development terms which seemed to favour the Washington consensus and international financial capital).

Another potential disadvantage of a highly centralized and hierarchical strategy in terms of command, control and accountability is that if an attempt at infiltration is successful, it is likely to do much more harm in a centralized command structure, leading to the possible adverse use and misdirection of all components of the system below the primary affected link and distorting the information and other feedback filtered ‘upwards’ to the control centre so that all relevant decisions taken by the infiltrated agency’s ‘superiors’ may be based on false or manipulated information.

Such acts of infiltration or collaboration can take a multitude of forms, from carefully planned and highly structured and organized long-term acts of infiltration (albeit executed covertly through a variety of secretive parallel and irregular or informal agreements) to spontaneous and opportunistic transactions, whether elaborated with the full consent of all parties involved or under conditions of extreme duress.

It is also likely to be much more difficult to identify and expose such an infiltration in such circumstances, as each components functions and activities – as well as the overall accountability structure – tend to be much less transparent and much crucial information is known only by a very limited number of ‘authorized’ officials and agents. In this context, a successful infiltration of one or more of the ‘apex’ components of the system inevitably has catastrophic consequences.

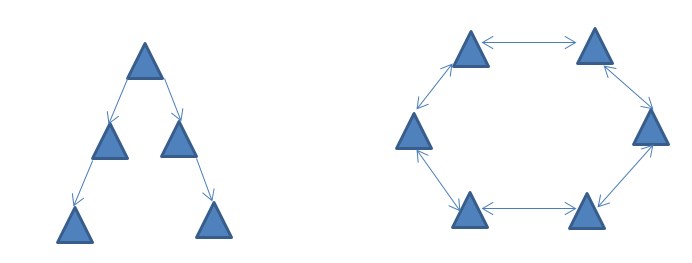

In conceptual terms, this can be represented as contrasting approaches adopting top-down hierarchical structures as opposed to overlapping and integrated networked systems in which each component of the system serves to complement, support and monitor the others in a mutually reinforcing manner instead of simply serving as transmission belts for the fulfilment of commands directed from ‘superior officers’. A simplified diagrammatic illustration would be as follows.

In the case of the centralized hierarchical model, the Office of the Presidency and the National Congress are at the apex. Although the two can be considered approximate equals in some respects, the former has primary responsibility for command, control and operational management functions while the latter has primary responsibility for supervision and accountability functions.

In the case of the integrated network model, all significant component parts have some degree of interaction and coordination with all other components to the extent that their functions and responsibilities have a reciprocal impact or common or related operational activities and objectives. Although such interaction and coordination of activities also occurs in an hierarchical system, it is generally quantitatively and qualitatively much less and usually constrained by the prevailing hierarchical arrangements. While the diagram has been greatly simplified for practical reasons, in operation it would include two-way information flows between each of the component parts as required, and the Office of the Presidency and the National Congress would be located in the centre.

Conclusion

As a final note, unless and until some of the directors and senior executives (as well as ‘independent’ auditors and regulatory officials) of the major banks that have laundered many billions of dollars of drug cartel money (such as HSBC and Wells Fargo – among many others) are sentenced with some serious jail time and the confiscation of their personal assets, it will be abundantly clear to all that the vast quantity of resources and many billions of dollars spent (and tens of thousands of lives lost) during the ‘war on drugs’ is a great tragedy and a complete farce, condemning a few convenient scape goats and many low level operatives to spend all or most of their lives behind bars, with a few high profile drug-busts and arrests (or extra-judicial executions) every now and then for public relations purposes (also serving to eliminate inconvenient competition, whistle-blowers or other potential troublemakers in more than a few cases) while vast swathes of society are criminalized, exploited and victimized for the benefit of a few people in the financial sector, the arms industries, the prison industry, and their political and bureaucratic collaborators and parasites.

Looks like cia’s plot yet again has been foiled,of course there are dreamers who implied no way,

lest it be reiterate,when it comes to real lifes dealings,no substitute for experience over pc hackers!

So sure of themselfs hey,read it n reap,truth has power,not live life as someone elses brain,hell no!

The democrats have a plan,to mess with in west coast,then assign + align before invading texas

and bring upon all kinds of havoc,so long as slave labour and easy to deal drug lords get in place

they will be only too happy,seens they remain in power,with virtually no opposition in hand,that is the idea,similar concept to do’minion,sadly law and order will diminish to the point of nazism,this case shows mexico is suffereing the trend,usa will be next,whilst nothings done about do’minion!

National Guard that has popular support are still deployed versus these gangs but gangs have the Dollars from USA drug trade… See also scandal under 06ama AG and ARMING of gangs… worked in Durango and South Coahuila Some years…. Army MX frequent military checkpoints on rural roads. Destabilization may be USA intention.

In all fairness, the CIA is the biggest cartel in Mexico and controls 90% of the drug trade.

They’re the biggest cartel in Afghanistan and I’d wager they control 100% of the drug trade there.

been going on since at least the late 70s.

99%*

Now that the Big Guy 10% is at the head of the US government, any profitable criminal activity will be promoted and increased.

The US does not like the new leadership in Mexico. Obrador has spoken out against the US and its evil. This may be their response.

All Mexican drug cartels are CIA trained, funded, armed and run.

Fact.

Monroe Doctrine…

fuera de los yanquis

South-front:Low profile vessel in first photo is Narco sub-marine and it is legend in drug traffic.Just contribution to your vocabulary.

Mexico needs a real revolution, but the population is too selfish and apathetic to bring this about. Most Mexicans don’t give a sh*t about anyone but their own kin. They have no sense of civic or patriotic duty; it’s a society that has tolerated crime and corruption since forever. And 90% of Mexicans are in total denial about this, so the situation will never improve because they don’t really accept there’s a problem with their society that goes all the way from the very top down to the bottom. The general attitude of Mexicans is: do whatever you can get away with.

These kinds of societies are easy pickings for the CIA.

It’s really a symptom of hopelessness. The order of which one places priorities would be family, extended family, religion (if applicable) and lastly nation.