Almost out of nowhere, the stage could possibly be set for a long and bitter war between Venezuela and Guyana (the latter enthusiastically ‘backed’ and egged on by the US and Exxon Mobil), driven in large part by stubbornness, greed, opportunism, provocative posturing and obviously mutually unacceptable unilateral claims over the enormous and mostly untapped natural resources in the disputed territory of Essequibo (Guayana Esequiba).

Although the rapid and decisive action taken jointly by many countries in the region (led by CARICOM and Brazil) pushing for a diplomatic solution have raised hopes that the two countries will return to the path of substantive dialogue and negotiations instead of hurling long distance threats, insults and insinuations, their respective claims to exclusive sovereignty remain fundamentally incompatible and the outbreak of hostilities cannot be ruled out (the armed forces of both countries have been put on high alert, and the US Southern Command has intensified its activities in Guyana at the same time as US officials – and Exxon Mobil – have expressed their unconditional support for Guyana).

In this context, in terms of a worst case scenario several preliminary observations can be noted. In raw realpolitik terms, although Venezuela enjoys a vast superiority in terms of overall military strength and capabilities, the enormous challenges posed by the vast and inaccessible terrain involved would make a large-scale invasion or occupation extremely difficult and risky (among other things, the armed forces throughout Latin America are not generally known for their agility and advanced logistical and technological capabilities). Moreover, the United States is well-placed to make sure that any invasion attempt by significant troop formations would be extremely costly: US military forces have extensive experience in the conduct of jungle warfare, reconnaissance, infiltration, sabotage operations and ‘high-value target’ training in the dense tropical jungles of Guyana and elsewhere throughout the region. The US elite and their slavish politicians, administrators and enforcers in the Congress, the White House and the Pentagon would like nothing more than to take advantage of such a golden opportunity to humiliate and inflict heavy casualties on its arch nemesis, having failed time after time in their constant regime change efforts over the last twenty-odd years. Amidst the heated rhetoric and uncompromising postures, one thing is certain: the last thing the world needs is another war.

Written by Daniel Edgar exclusively for South Front

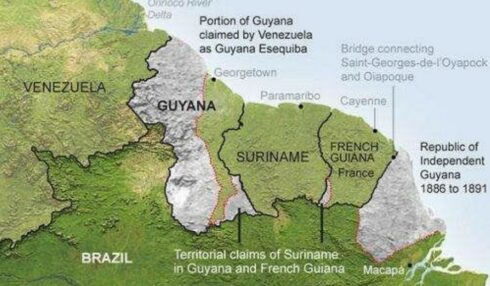

The disputed Esequibo region (called Essequibo in Guyana and Guayana Esequiba in Venezuela) is a vast but sparsely populated area (approximately 160,000 square kilometres) covered by extensive tracts of tropical forest and reputed to contain abundant and largely untapped natural resource wealth, possibly including very substantial quantities of gold, diamonds, bauxite, hydrocarbons, copper and iron as well as enormous biological diversity and fresh water sources. The region amounts to around two thirds of Guyana’s total (claimed) territory and a bit over one eighth of the country’s population (approximately 125,000 inhabitants of a total of just over 800,000, most of whom live in the coastal regions of Guyana proper). The length of the de facto border is over 800 kilometres, stretching from the Atlantic Ocean (Caribbean) to Brazil. There are very few major transport corridors (or even basic paved roads) within the region, there are no direct transport links between Venezuela and Guyana (the main transport route between the two countries is via separate road connections from each country to a highway in Brazil), and the territories subject to dispute are traversed by numerous large and fast-flowing rivers.

Background events leading up to the sudden flare-up in the border dispute

For the most part bilateral relations between the two neighbouring countries have been almost non-existent, amounting to a condition of benign neglect and indifference, mostly due to their very different colonial trajectories and contemporary social characteristics (particularly the language barrier). More generally, the geographically and culturally anomalous colonial remnants of Guyana, Suriname and French Guyana (located in the far north east of South America) are unknown to the rest of Latin America. Prior to the latest crisis very few people in the region would have been able to find Guyana on a map.

The regional context – ‘Las Guyanas’

The broader biogeographical region around Guyana is referred to by some as “Las Guyanas”. The three adjacent territories/ countries of Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana are the leftover fragments produced by a series of chaotic and opportunistic Dutch, French and British imperial adventures over the course of several centuries. They remain largely uninhabited and almost completely unknown to the rest of the world. Throughout their history (since European invasion) they were neglected outposts of the respective Dutch, French and British Empires, acquired by way of a succession of military invasions and incursions over successive periods as the European powers sought to expand their dominions and out-manoeuvre their rivals at every opportunity.

The area currently constituted as The Cooperative Republic of Guyana was first claimed by the Dutch in the 1600s before falling to the British in the early 1800s, and remained a British colony until its formal independence in 1966 (although the total area claimed by Guyana is around 240,000 square kilometres, it has unresolved border disputes with both Venezuela and Suriname with respect to over two thirds of that area). To the east, the neighbouring Republic of Suriname (with a territory of just over 630,000 square kilometres and around 590,000 inhabitants – a cultural melting pot of Hindus, Muslims, Catholics, Protestants, along with the survivors of the original Indigenous inhabitants) remained a Dutch colony until 1975. Further to the east, the overseas department of French Guiana (of 83,500 square kilometres and just over 300,000 inhabitants) remains a French colony (the ‘Territorial Collectivity of French Guiana’ and the ‘outermost region of the European Union’), where even the European Space Agency has joined the colonial adventure taking advantage of the launching facilities constructed by the French (Guiana Space Centre) for their space program.

The overall tenor of each country/ territory’s economic and foreign relations orientation and priorities is indicated by their main trade partners – most of the exports and imports of French Guiana (total GDP approximately $4 billion euros, main exports fish, timber and gold) are of course with France. The major trading partners of Suriname (total GDP around US$3 billion, the economy is dominated by the production of aluminium which until recently accounted for 15% of GDP and two-thirds of all exports, the reminder consisting of other primary materials and products such as oil, gold, rice and seafood) are as follows: most exports are to Switzerland (48%), UAE (30%), US (8%), China (2.3%) and Belgium (2.3%). Most imports are from the US (23%), China (21%), Netherlands (19%), Japan (4.4%) and last (but not least) neighbouring Brazil (2.9%).

The major trading partners of Guyana (total GDP around US$16 billion, the main export products have traditionally been bauxite, gold, timber, rice and sugar) are as follows: most exports go to the US (26%), Canada (13%), Trinidad and Tobago (9%), Jamaica (6%) and the UAE (6%). Most imports are from the US (25%), Portugal (16%), Trinidad and Tobago (10%), China (10%) and the UK (4%).

These basic data are sufficient to get an idea of the region’s continued condition as a cluster of isolated neo-colonial outposts and enclave economies based on the exploitation of natural resources and other primary commodities with very little in the way of integral social and economic development and regional cooperation. In this respect a report prepared by the US Congressional Research Service (2023) states of the dominant factors that have influenced Guyana’s traditional social and cultural makeup, political institutions and international relations and orientation:

Guyana has characteristics similar to other Caribbean nations because of a common British colonial heritage… The country participates in Caribbean regional organizations, and its capital, Georgetown, serves as headquarters for the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), a regional integration organization. Once one of the poorest countries in the hemisphere, Guyana’s development prospects have shifted significantly since the discovery of large offshore oil deposits in 2015…

The country’s traditional emphasis on political and economic relations with the other post/ neo-colonial island States and offshore territories of the UK, the US, France and the Netherlands in the Caribbean – and the deeper ties and relations with the neo-Imperial metropoles of the UK and the US in particular – rather than on interactions with the neighbouring States of South America is an important background aspect underlying and influencing the course of the current dispute with Venezuela.

Background of the territorial dispute between Guyana and Venezuela

Although the expansion of colonial settlement and occupation did not reach the disputed areas between Guyana and Venezuela until relatively recent times, in the late nineteenth century both the British and Venezuela claimed exclusive sovereignty. In 1899 the Paris Arbitration Tribunal ruled in favour of Britain in proceedings in which Venezuela did not participate directly (and two of the four members of the ‘international tribunal’ were British). This ruling was superseded in 1966 by the Geneva Agreement, the result of direct negotiations between the United Kingdom and Venezuela but also deemed to be binding on Guyana which was granted independence later that same year (the terms of which Guyana readily accepted at the time).

Given the contradictory assertions and claims that have been made by the respective parties to the dispute as to the fundamental principles and terms of the 1966 Geneva Agreement, assertions which have for the most part been uncritically echoed in the media, it is worth citing the key terms of the document in full. The Agreement between Venezuela and the United Kingdom “to resolve the controversy over the frontier between Venezuela and British Guiana” was signed in Geneva on the 17th of February 1966 and was formally registered with the UN several months later. Article VIII provided that following the attainment of independence by British Guiana, the Government of Guyana would thereafter be a party to the Agreement, in addition to the Governments of the United Kingdom and Venezuela. The preamble states:

The Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, in consultation with the Government of British Guiana, and the Government of Venezuela;

Taking into account the forthcoming independence of British Guiana;

Recognising that closer cooperation between British Guiana and Venezuela could bring benefit to both countries;

Convinced that any outstanding controversy between the United Kingdom and British Guiana on the one hand and Venezuela on the other would prejudice the furtherance of such cooperation and should therefore be amicably resolved in a manner acceptable to both parties;

In conformity with the agenda that was agreed for the governmental conversations concerning the controversy between Venezuela and the United Kingdom over the frontier with British Guiana, in accordance with the joint communique of 7 November, 1963, have reached the following agreement to resolve the present controversy:

Article I

A Mixed Commission shall be established with the task of seeking satisfactory solutions for the practical settlement of the controversy between Venezuela and the United Kingdom which has arisen as the result of the Venezuelan contention that the Arbitral Award of 1899 about the frontier between British Guiana and Venezuela is null and void…

The following Articles stipulate that the Mixed Commission to be created by the Governments of Venezuela and British Guiana was to comprise two representatives appointed by each government (the members of the Commission also being empowered to appoint consultants to provide additional advice and expert opinion on related matters), and that the Commission was to provide an interim report at six month intervals for a period of four years. According to Article IV of the 1966 Agreement:

(1) If, within a period of four years from the date of this Agreement, the Mixed Commission should not have arrived at a full agreement for the solution of the controversy it shall, in its final report, refer to the Government of Guyana and the Government of Venezuela any outstanding questions. Those Governments shall without delay choose one of the means of peaceful settlement provided in Article 33 of the Charter of the United Nations.

(2) If, within three months of receiving the final report, the Government of Guyana and the Government of Venezuela should not have reached agreement regarding the choice of one of the means of settlement provided in Article 33 of the Charter of the United Nations, they shall refer the decision as to the means of settlement to an appropriate international organ upon which they both agree or, failing agreement on this point, to the Secretary-General of the United Nations. If the means so chosen do not lead to a solution of the controversy, the said organ or, as the case may be, the Secretary-General of the United Nations shall choose another of the means stipulated in Article 33 of the Charter of the United Nations, and so on until the controversy has been resolved or until all the means of peaceful settlement there contemplated have been exhausted…

One other provision is of particular importance given the accelerated approval and implementation of major economic development projects in disputed areas over the last ten years undertaken unilaterally by the Guyanese Government.

Article V

(1) In order to facilitate the greatest possible measure of cooperation and mutual understanding, nothing contained in this Agreement shall be interpreted as a renunciation or diminution by the United Kingdom, British Guiana or Venezuela of any basis of claim to territorial sovereignty in the territories of Venezuela or British Guiana, or of any previously asserted rights of or claims to such territorial sovereignty, or as prejudicing their position as regards their recognition or non-recognition of a right of, claim or basis of claim by any of them to such territorial sovereignty.

(2) No acts or activities taking place while this Agreement is in force shall constitute a basis for asserting, supporting or denying a claim to territorial sovereignty in the territories of Venezuela or British Guiana or create any rights of sovereignty in those territories, except in so far as such acts or activities result from any agreement reached by the Mixed Commission and accepted in writing by the Government of Guyana and the Government of Venezuela. No new claim, or enlargement of an existing claim, to territorial sovereignty in those territories shall be asserted while this Agreement is in force, nor shall any claim whatsoever be asserted otherwise than in the Mixed Commission while that Commission is in being…

The Mixed Commission created pursuant to the Geneva Agreement of 1966 couldn’t resolve the dispute, and the alternative provisions for settlement of the dispute (invoking Article 33 of the UN Charter) were pursued by both parties until as late as around 2015 – the last meeting between the respective Heads of State, Presidents Nicolas Maduro and Donald Ramotar, was in 2013. The State-owned media outlet Guyana Chronicle (“Venezuela guilty of breaching international obligations”, 12 December 2023) describes the long course of diplomatic procedures that were established over successive periods to try to work towards a pacific solution: “Efforts of more than half a century, including a four-year Mixed Commission (1966-1970), a twelve-year Moratorium (1970-1982), a seven-year process on a means of settlement (1983-1990), and a twenty-seven-year Good Offices Process under the UN Secretary-General’s authority (1990-2017) have been futile thus far…”

The last of the bilateral accords providing a format for negotiations to resolve the dispute (the ‘Good Offices Process’) formally expired in 2017, though it was for all intents and purposes dead and buried some time before that having been unilaterally and irrevocably abrogated when Guyana began granting extensive exploration concessions in the disputed maritime zone. Throughout this period Guyana remained the de facto administrator of the disputed territory.

The termination of the Good Offices Process

Although the terms and provisions of the Good Offices Process had been neglected and undermined by ongoing developments for some time, the Accord was effectively abandoned and ultimately terminated in 2015 when Exxon announced the discovery of the vast offshore oil and gas fields in the disputed zone. The Guyanese Government insisted in public statements several years later (Oilnow, 6 February 2018, “The Good Offices process as Guyanese know it has finished – VP Greenidge”) that all of the diplomatic procedures envisaged by the 1966 Accord had run their course without the most minimal progress in terms of finding a viable solution and that the Accord was of no further relevance. The newspaper article commented of these developments:

Venezuela has objected to a decision by the UN Secretary General (Antonio Gueteres) to refer its border objections with Guyana to the International Court of Justice (upon the request of the Guyanese Government), calling instead for (a continuation of the) Good Offices mechanism.

The former British colony is having none of it however, with its Minister of Foreign Affairs, Vice President Carl Greenidge declaring, “the good offices process as Guyanese know it has finished, it has been completed…

In statements reported in the media at the time then Vice President Carl Greenidge was adamant that Venezuela must accept the jurisdiction of the ICJ to make a binding ruling, despite the emphasis throughout the 1966 Geneva Agreement that both parties must agree before the matter could be referred to any specific alternative arbitration procedure, international agency or tribunal, and that none of the alternative procedures envisaged by the agreement (which invokes Article 33 of the UN Charter as a measure of last resort) even mention the International Court of Justice. Specifically, Article 33 of the UN Charter (titled ‘Pacific Settlement of Disputes’) states:

-

The parties to any dispute, the continuance of which is likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace and security, shall, first of all, seek a solution by negotiation, enquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, judicial settlement, resort to regional agencies or arrangements, or other peaceful means of their own choice.

-

The Security Council shall, when it deems necessary, call upon the parties to settle their dispute by such means.

Although referral to the Office of the UN Secretary General is specifically mentioned in the 1966 Agreement as “one of the means of peaceful settlement” of the UN Charter to be invoked in the event no agreement had been possible, it is only one of many alternatives stipulated in a context in which the explicit agreement and consent of both parties to submit the dispute to a third party for arbitration is repeatedly mentioned as a fundamental principle.

Moreover, the decision to refer the dispute to the ICJ was precipitated at a time when Guyana had clearly violated the terms of the Accord by unilaterally granting exploration and exploitation concessions in one of the disputed areas in circumstances that strongly suggest the Guyanese government was seeking to gain a procedural advantage by adopting that particular course and renouncing the possibility of any alternative dispute resolution framework based on ongoing dialogue and negotiation.

Border disputes between Guyana and Suriname

In this context, it is worth noting that Guyana also has a long-standing unresolved border dispute with its neighbour to the east (Suriname), which as noted above attained independence from the Dutch in 1975 and must be observing current developments very closely. The disputed section of the border with Suriname is referred to as The New River Triangle or Tigri Region (and is also substantial, amounting to 15,600 square kilometres), and the two countries also had a longstanding disagreement over the maritime boundary.

The dispute over the location of the maritime boundary between the two countries ultimately reached flashpoint in 2000 when a company registered in Canada (CGX Energy Inc.) placed an offshore oil rig in the disputed area claiming exploration rights pursuant to a concession granted by Guyana (at that time the current Vice President of Guyana, Bharrat Jagdeo, was president). Shortly afterwards the oil rig was captured and removed from the area by Suriname’s navy pending settlement of the dispute (the rig had not yet commenced drilling operations). While CGX Energy Inc. promoted and supported the full extent of Guyana’s claims, Suriname’s territorial claim was backed by the oil companies Repsol YPF (based in Spain) and MAERSK (based in Denmark), each of which held concessions conferred by the government of Suriname (CORPWATCH, 2005).

The dispute was finally referred to an international arbitration panel pursuant to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea’s ruling was accepted by both countries in 2007. The dispute over the terrestrial border with Suriname still has not been resolved. (Venezuela has not had other major territorial disputes with its South American neighbours, while a lingering set of maritime border disputes with the Kingdom of the Netherlands were ultimately resolved pursuant to a treaty signed by both countries in 1978).

Recent developments in the territorial dispute between Venezuela and Guyana

After several years of rising tensions and increasingly strident but essentially harmless patriotic posturing on both sides, almost out of nowhere in early December of this year it appeared that the age-old border dispute between Venezuela and Guyana could be fast approaching the point of no return, with both countries claiming exclusive sovereignty over the entirety of the disputed territories, expressing their determination to make good their claim, and appearing to be actively taking steps to do so (including placing their Armed Forces on High Alert).

The Government of Guyana must have known when it started unilaterally granting exploration permits in the disputed maritime zones (with both Venezuela and Suriname) that this would lead to major problems with its neighbours sooner or later. The companies involved also must have known that the international maritime boundaries had not been settled and were the subject of ongoing disagreement between the countries involved.

Although the first offshore exploration concessions were granted in 1999 and Exxon commenced exploration activities in the disputed offshore area between Venezuela and Guyana in 2008, the stakes involved in the crisis that inevitably followed multiplied exponentially when the foreign consortium led by Exxon Mobil discovered huge reserves of oil and gas in the concession area in 2015 and almost immediately commenced production (production started in 2019 and quickly reached around 400,000 barrels per day (bpd), over half that of Venezuela whose production dropped from well over two million bpd at its peak to less than 800,000 after the imposition and vigorous enforcement of draconian extraterritorial financial sanctions and a strict economic blockade by the US). In November of this year a third autonomous offshore production platform (‘Floating, Production Storage and Offloading vessel’) came on line, which is projected to lift Guyana’s total oil production to 620,000bpd by next year. The total hydrocarbon reserves in the disputed area are reported to be among the largest in the world (the U.S. Geological Survey has estimated total reserves of 13.6 billion barrels of oil and 32 trillion cubic feet of gas).

While the consortium formed to conduct exploration and production activities includes participants from other countries (including one of the Chinese State-owned oil companies, CNOOC), Exxon Mobil is the major partner and is responsible for the project’s operational management (Exxon’s subsidiary Exxon Mobil Guyana Limited has a 45% stake, Hess Guyana Exploration Ltd has 30%, and CNOOC Petroleum Guyana Limited 25%). Meanwhile, as noted above the Canadian-based firm CGX Energy Inc. has also been conducting offshore exploration in the region for some time. More recently, since January of 2023 the Ali administration has been engaged in talks over the allocation of other offshore blocks for oil and gas exploration with representatives from Qatar, the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates and India.

In early December of this year Guyana’s Vice President reiterated his government’s posture that all negotiations conducted through formal and mutually agreed diplomatic procedures have been terminated and that Venezuela must accept the decision to refer the dispute to the ICJ. A media report describing the government’s latest official statements also reveals the immensity of the Exxon Mobil-controlled offshore project:

Maintaining that Guyana has the right to pursue development in every inch of its territory, Vice-President Dr Bharrat Jagdeo has said that the evolution of the nation’s economy will not stop. “If we pause any of our development, Maduro succeeds. Maduro has no right in international law to tell the people of Guyana, [a] sovereign country, how to pursue its affairs. And that is why we are forging ahead with our development in all 83,000 square miles”…

Dr. Jagdeo further said that his government will not become “paralysed” and fall prey to the Bolivarian Republic’s tactics…

The 2023 International Monetary Fund (IMF) report revealed that Guyana’s real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is expected to continue its rapid growth. Guyana achieved the highest real GDP growth in the world in 2022 – 62.3 per cent. Guyana’s economy has tripled in size since the start of oil extraction (in 2019). In the early 90s it had one of the lowest GDPs per capita in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Meanwhile, the US has of course been enthusiastically ‘meddling’ in the dispute and throwing fuel on the smouldering embers, expressing unconditional support for the full extent of Guyana’s unilateral territorial claims and ambitions and using the soaring tensions to persuade the Government of Guyana to approve ever more frequent and extensive ‘joint’ military exercises in the country. Over the last month the US and Guyanese governments have been reported as being in favour of establishing a long-term US military presence at bases not only in Guyana proper but also in the disputed regions adjacent to the de facto border with Venezuela.

A series of bilateral and ‘international’ or ‘regional’ military exercises and war games have been held in Guyana over the last year, all of which were organised and commanded by the US. The largest of these (“Exercise Tradewinds”) was held in July for two weeks with the participation of 1,500 military personnel from over twenty countries under the leadership of US Southern Command (the US also contributed the overwhelming majority of the participating military personnel). The series of military exercises, tasks and operations included “jungle certification, airborne wing exchange, oil spill and flood simulation, and human rights and Women, Peace and Security Training”.

In the days following the referendum held in Venezuela in early December the US added regular surveillance flights along the de facto border to its repertoire of military/ intelligence assets and activities in Guyana (which also includes a previously existing International Military Education and Training program). According to reports in late November of this year, there is also an unspecified number of personnel from the US Army 1st Security Force Assistance Brigade deployed to Guyana on a ‘capacity building mission’.

Apart from greatly aggravating tensions and hostility and thereby raising the risk of a mutually devastating war breaking out (which could however serve Washington’s geopolitical interests and objectives very nicely) whether by accident or by design, the prospective implantation of substantial US military outposts in the de facto border zone is not surprisingly considered by the Venezuelan Government to be a major and direct threat to its national security given the openly declared and clearly demonstrated obsession of the US elite with overthrowing the Venezuelan Government by any and all means possible over the last twenty years.

Although throughout its history since achieving formal independence the Government of Guyana has on numerous occasions adopted a strong position of actively maintaining and defending its independence and sovereignty in its bilateral and international relations, as mentioned previously the US military has nonetheless managed to acquire extensive experience in the conduct of reconnaissance activities, exercises and war games throughout the country, and no doubt has much better knowledge of the terrain in terms of the enormous variety of militarily-relevant geographical features and other details that could affect military operations than the armed forces of either Guyana or Venezuela. It is illustrative in this sense that a report produced by the FAO in 2015 (“Country Profile – Guyana”) cites the US Army Corps of Engineers as the source for information on the maximum, minimum and average annual flow of selected rivers in Guyana.

More recently the United Kingdom has also sought to join the fray, sending a naval patrol boat (HMS Trent) to Guyana (barely a week after a bilateral meeting between the presidents of Guyana and Venezuela at which they agreed to resume negotiations and refrain from taking any steps that could aggravate the dispute, discussed below). The deployment has been variously referred to as ‘routine’ by UK and Guyanese officials while at the same time being described in other statements as a demonstration of the UK’s unconditional support for Guyana’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. This cynical act of Guyana’s former colonial power was condemned by the Venezuelan Government as a blatant violation of the agreement signed at the bilateral meeting on the 14th of December (the Argyle Agreement), and Venezuela responded by announcing the immediate deployment of a combined military task force to the border area (reported to consist of between 5,000 and 6,000 personnel).

The rapidly deteriorating situation during the first days of December prompted the leaders of the members of CARICOM (the Caribbean Community) as well as neighbouring Brazil to take urgent measures seeking to de-escalate the dispute and reactivate diplomatic procedures, direct dialogue and negotiations. Most of the governments of South America also issued a joint statement calling for calm and a return to direct dialogue and negotiations shortly afterwards. During a regional meeting of the members of Mercosur (Mercado Común del Sur) on the 8th of December, the governments of Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru expressed “their profound concern over the increase in tensions” between Caracas and Georgetown. The joint declaration further states that “Latin America must be a territory of peace”, urging both countries to resume “dialogue and to search for a pacific solution to the controversy” and “to avoid unilateral actions and initiatives that could aggravate” the dispute.

Against all odds CARICOM and Brazil managed to persuade the presidents of Guyana and Venezuela to meet in mid-December. Although the atmosphere of the meeting was tense and it only lasted a few hours, the two leaders agreed to sign a ‘Joint Declaration of Argyle for Peace between Guyana and Venezuela’ (‘the Argyle Agreement’). The document contains eleven points, including that neither country will threaten the use of force against the other, their determination that controversies will be resolved in accordance with international law, and to refrain from taking any steps that could escalate the conflict. The two countries also agreed to establish a Joint Commission comprising delegates appointed by their respective foreign ministries to consider such matters as may be referred to the Commission in the future, and to meet in Brazil within three months to continue discussions (a meeting that will also be accompanied by senior delegates from CELAC, CARICOM and numerous individual States in the region).

A Preliminary Survey of Some Alternative Scenarios

Before going into a detailed analysis of the political, economic and geopolitical dimensions affecting the course of the dispute, some of the alternative scenarios that could conceivably develop (albeit some of which are extremely unlikely) are sketched out to provide a basic conceptual and contextual framework for the analysis that follows. While of course there is always the likelihood of completely unexpected developments occurring, some possible basic scenarios for the future course of developments related to the dispute include –

NEGOTIATED AGREEMENT SCENARIOS

* The Venezuelan Government (and people) accept the Guyanese Government’s position and the ICJ decides the dispute. (Very unlikely to inconceivable at this point.)

* The Guyanese Government (and people) accept the Venezuelan Government’s assertion of exclusive sovereignty. (Also very unlikely to inconceivable).

* The Guyanese and Venezuelan Governments agree to negotiate in good faith to reach a mutually acceptable solution. (Also currently unlikely, though perhaps not inconceivable given the recent success of CARICOM and Brazil to get the two parties two agree to meet resulting in an agreement to reactivate a Joint Commission to investigate related topics).

* One of the governments accepts the other’s position under duress but the decision is rejected by the people (and/ or by powerful vested interest groups opposed to the government), resulting in social and political turmoil and a possible change of government. (Technically possible but also unlikely.)

* The US finally succeeds in its interminable scheming to overthrow the Venezuelan Government and arranges for the instalment of a regime subservient to it, which ultimately accepts the status quo – perhaps with a small consolation ‘concession’ offered by the US (via Guyana) in order to assuage public sentiment. (Very unlikely, unless the Venezuelan Government is conclusively thwarted in its efforts to conclude a mutually acceptable arrangement or, if progress towards such a negotiated agreement remains impossible, if the Venezuelan Government is unable to effectively take over and incorporate at least some significant portions of the disputed territory and suffers heavy casualties in the process).

* The (US-backed) Venezuelan opposition wins the presidency and/ or a majority in the National Assembly in the elections scheduled to be held in 2024. (It is unclear how this might affect Venezuela’s territorial claims and/ or its disposition to negotiate in good faith with Guyana.)

CONFLICT SCENARIOS

* Incremental military occupation of and control over disputed areas by each party: Each side expands the deployment of military forces to currently unoccupied areas and strategic zones to incrementally occupy and secure control over specific localities and regions to the extent that each sides’ respective military capabilities and local circumstances and conditions permit (with Guyana’s armed forces most likely accompanied by a limited number of US military personnel – along with an unlimited number of mercenary forces contracted by the Pentagon or rather, the number of mercenaries being limited only by the availability of cheap cannon fodder, which is abundant in the region).

Direct confrontation and combat might generally be avoided by both sides in order to limit the risk of a major conflagration, but occasional or regular skirmishes would be a distinct possibility along with actions of sabotage and subversion from each side against the other with the objective of delegitimizing their rival’s claims and making effective occupation untenable. Each side would also presumably seek to weaken and destabilize the other in terms of the government’s hold on power, taking advantage of the profound internal differences, fissures and schisms that already exist in each country. (Appears to be a feasible development at this point, leading either to a negotiated solution once the enormous costs and losses involved begin to mount, or possibly leading to intractable ‘low intensity conflict’ and ‘hybrid warfare’ for a lengthy period – or until one side or the other is exhausted and/ or overthrown by some combination of internal or external actors and forces. Alternatively, such a scenario could eventually build up to a formal declaration of war and major conflict).

* A declaration of war and major conflict: Ultimately, neither side can realistically hope to effectively occupy and control the entire area in the face of active counter-measures and resistance by the other – it would take 160,000 troops just to have one soldier in each square kilometre. Presumably each side would also try to induce or persuade the residents in each region to support their actions and maybe try to form local armed militias to bolster their forces and capabilities, in which case local perceptions and attitudes would be crucial.

Some of the key factors and questions in such a war scenario include would the US attack major military targets in Venezuela directly, and correspondingly whether the Venezuelan armed forces have managed to obtain advanced weapons systems from Iran, Russia and/ or China (long range missiles, anti-aircraft and anti-ship missiles, for example) capable not just of defending itself against a large-scale attack by the US but of hitting strategic US assets in the region. While it is certain that the US could inflict heavy losses on Venezuela (in terms of both military and civilian personnel, infrastructure and equipment), it is possible that Venezuela may also be capable of inflicting heavy losses on the US.

Final preliminary comments

The incremental military/ civilian occupation of border areas and communities as well as strategic points throughout the disputed areas appears to be one of the most likely developments in the immediate future, given that both sides remain adamant in their respective claims to exclusive sovereignty. Initial reports of activities of the FANB along the de facto border suggest this may in effect already be occurring in some areas. However, the establish of the Joint Commission in mid-December and the agreement of the two Heads of State to meet again in Brazil within three months provides an opportunity for this to be avoided (or perhaps even shifted towards a competition to establish civilian infrastructure and provide essential services in remote and regional communities instead of a race to establish military outposts and territorial occupation, taking an overtly optimistic point of view on the possible future course of events).

Summary of key political developments and geopolitical factors in Venezuela

While its real intentions and plans remain unknown, the Venezuelan Government could be taking a huge gamble with its stated intention of incorporating the disputed Esequibo region within Venezuela with immediate effect, by raising the expectations of the Venezuelan people well beyond what would seem to be a realistically feasible outcome. That is, if the immediate integration or ‘reclamation’ of the entire territory is indeed the Government’s intention; it could of course be staking out such a vehement ‘winner takes all’ posture more in the nature of a rhetorical device and tactical move to demonstrate Venezuela’s determination to finally reach a mutually satisfactory agreement before it is too late, as well as trying to strengthen its bargaining position in negotiations.

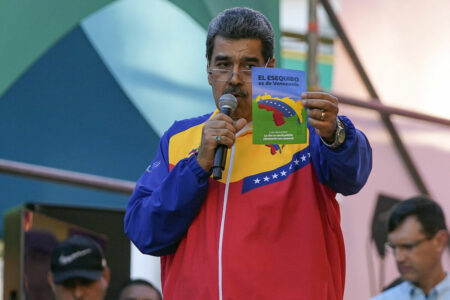

The referendum on ‘Guayana Esequiba’ and related developments

The referendum in Venezuela that was held on the 3rd of December included a provision explicitly rejecting the legitimacy and validity of the 1899 Paris Arbitration Tribunal ruling, and another supporting and reaffirming the Government’s decision not to recognise the jurisdiction of the ICJ to decide the dispute. Meanwhile, the key question postulated asks if the voter is in agreement with the creation of the State of Guayana Esequiba as an integral part of Venezuela, along with the accelerated implementation of a plan for social integration and economic development that includes the granting of Venezuelan identity documents and citizenship to all residents in the relevant territories. Nonetheless, the other terms of the provision stipulate that this will be done pursuant to and in conformity with the Geneva Agreement of 1966 and International Law, and the Venezuelan Government has repeatedly reaffirmed its willingness to enter into discussions with Guyana without preconditions.

President Nicolas Maduro forwarded a proposed Law to the National Assembly shortly after the referendum (the “Organic Law for the Defence of Guayana Esequiba” – Ley Orgánica por la Defensa de la Guayana Esequiba) to establish the founding principles and administrative arrangements for the creation of the new state, and also promulgated a series of executive decrees and orders to formalize the transitional governmental structures responsible for planning and administering the new provisions. Central features of the new decrees and institutional arrangements include:

* A High Commission for the Defence of Guayana Esequiba (Alta Comisión por la Defensa de la Guayana Esequiba) headed by Vice President Delcy Rodriguez and charged with overseeing and coordinating the management of all activities related to the integration of the new province into Venezuela’s sovereign territory and system of government;

* The creation of a Zone for the Integral Defence of Guayana Esequiba (Zona de Defensa Integral de la Guayana Esequiba) headed by Major General Alexis Rodriguez Babello, comprised of three geographic areas and responsible for 28 operational sectors and related logistical arrangements for the planning and implementation of the integral social and economic development strategy together with the National Bolivarian Armed Forces of Venezuela (headquartered in Tumeremo in the state of Bolivar and administratively and militarily dependent on the Integral Defence Region of Guayana – Región de Defensa Integral Guayana);

* A provision authorizing PDSVA and Corporación Venezolana de Guayana (the State-owned petroleum and steel producers respectively) to create regional subdivisions empowered to grant concessions for the exploration and exploitation of oil, gas and minerals in the new province;

* The activation of a Social Plan for the Provision of Public Services (Plan de Atención Social) and the initiation of a census of residents in the new province to recognize them as Venezuelan citizens;

* The prohibition of contracts, licences or commercial relations with companies involved in or collaborating with any project pursuant to the unilateral concessions granted by Guyana in the maritime zone whose territorial limits are yet to be defined;

* A request to the National Assembly to approve a special law to create environmental protection zones and national parks in the territory of Guayana Esequiba.

The proposed legislation and all relevant decrees providing measures necessary for the formal incorporation of the disputed territory into Venezuela and for its subsequent administration were unanimously approved by the National Assembly within days and is currently subject to a period of ‘public consultation’.

Adding to the zero sum, all or nothing quagmire/ stalemate that the territorial dispute has reached, the Maduro Government is speaking and acting as though the incorporation of the disputed territory is a foregone conclusion, with only the technical and administrative details to be sorted out. As noted above, one of the first announcements of the Government in the aftermath of the referendum was the ordering of procedures to unilaterally grant mineral and energy exploration permits throughout the disputed territory, thereby taking the same course of action as that previously taken by the Guyanese Government which resulted in the dispute reaching such an antagonistic and potentially explosive crisis point in the first place.

Even more ominous in terms of the prospect that the dispute could suddenly deteriorate into a catastrophic and prolonged military confrontation notwithstanding the détente achieved by the bilateral meeting in mid-December and the Argyle Agreement, the Venezuelan Government has demanded that all existing resource development projects in the disputed maritime region (that is, Exxon Mobil’s already enormous offshore oil and gas production facilities) terminate operations within three months pending the conclusion of a new agreement with Venezuela (it is not clear if a similar ultimatum applies in terrestrial areas, where there are countless large-scale logging, mining and other commercial activities, both legal and illegal). Although Maduro has avoided using the language of a military occupation and forced integration of the territory, that is currently the only way his stated intentions could be achieved.

Nonetheless, in this sense it should also be acknowledged that anything less than the adoption of such a vehement posture (possibly accompanied by a series of strategic military infiltrations leading up to the consolidation of significant areas under direct Venezuelan occupation and control throughout the disputed region) would be equivalent to a tacit acceptance of the status quo, similar to the stalemate that exists in the Falkland Islands/ Malvinas dispute between the United Kingdom and Argentina where the only thing that would be capable of altering the UK’s unilateral territorial claims and de facto sovereignty over the disputed areas (which, according to international law, belong to Argentina) is a successful Argentine military intervention. In such a situation possession is nine-tenths of the law. The other tenth is the ability to sustain effective territorial occupation.

Some recent media reports (in particular “Venezuela. FANB realiza jornada de atención integral en Guayana Esequiba”, Aporrea, 12 December 2023) suggest that a strategy of incremental joint military/ civilian territorial occupation may indeed already be underway, with rapid reaction forces of the Venezuelan armed forces reported to be conducting security patrols along and across the other side of the de facto border accompanied by integrated civilian security teams who are also providing free health services to remote communities:

The National Bolivarian Armed Forces (Fuerza Armada Nacional Bolivariana, FANB) continue in their deployment to provide integral attention to the residents of Guayana Esequiba, according to a communiqué by the strategic operational commander of the FANB (G/J Domingo Hernández Lárez)…

In another publication, commander G/J Domingo Hernández Lárez emphasized that the Rapid Response Units (Unidades de Reacción Rápida) of the FANB are conducting night patrols in the area together with personnel from the Citizens’ Security Units (Organismos de Seguridad Ciudadana) to guarantee the security of residents…

He also commented that the security forces are making regular visits to the frontier townships to guarantee the honour and liberty of the inhabitants…

Venezuela: The Political Landscape and Major Social and Economic Factors

In terms of Venezuela’s always complicated, polarized, animated and volatile political situation, beyond the temporary surge of patriotic demonstrations and hubris lies a multitude of challenges and obstacles, as well as imminent risks and dangers. There are many sectors within Venezuelan society that have been critical of the Government’s policies and performance for some time, stemming from many different perspectives and for very different reasons. More generally, the Government’s inability to clearly and decisively identify, explain and resolve the structural causes that have resulted in many years of intense economic scarcity and hardship is a constant and profound source of concern for all Venezuelans. The prolonged economic crisis was produced by a combination of complex geopolitical, administrative and economic factors such as the crushing extraterritorial economic embargo and financial sanctions imposed against Venezuela by the US, instances of financial and economic mismanagement by the Government and State officials, and widespread practices of cronyism, fraud and corruption both in State institutions as well as in the private sector.

Preliminary comments on the historical context and analytical perspectives

In order to establish a clearer conceptual and contextual basis for the political analysis that follows, veteran Latin America scholar James Petras provides an excellent overview of the 2012 presidential campaign in Venezuela that clearly explains the key ideological and programmatic characteristics and objectives of the opposed candidates and the social sectors behind them.

I strongly recommend the article to readers in the US in particular, where definitions, concepts and interpretations of left-wing and right-wing ideological premises and political forces, factions and interest groups is extremely muddled and confusing. Leftist policies, factions and groups are variously referred to in the US as ‘progressive’, ‘populist’, ‘liberal’, ‘socialist’ or ‘communist’ (the latter two invariably condemned as subversive and irrational political heretics), and right-wing factions are usually referred to as ‘conservative’, in some contexts ‘neo-liberal’ or ‘neo-conservative’. Many commentators and analysts also often seem to associate ‘leftist’ ideologies and policies with anything the Democrats favour, and rightist ideologies with anything the Republicans favour. Meanwhile, there is much evidence supporting the veracity of Howard Zinn’s conclusion that both major political parties ultimately represent and serve the country’s economic elites above all else. To very briefly summarize some of the key points made from this perspective:

The stories of class struggle in the nineteenth century are not usually found in text books on United States history. That struggle is most often obscured by the pretence of intense conflict between the major political parties, although both parties have represented the dominant classes of the nation…

It was the new politics of ambiguity – speaking for the lower and middle classes to get their support in times of rapid growth and potential turmoil. To give people a choice between two different parties and allow them, in a period of rebellion, to choose the slightly more democratic one was an ingenious mode of control…

(In more recent times however there has been) a troubling incongruity in the society. Electoral politics dominated the press and the television screens, and the doings of presidents, members of Congress, Supreme Court justices and other officials were treated as if they constituted the history of the country. Yet there was something artificial in all this, something pumped up, straining to persuade a skeptical public that this was all, that they must rest their hopes for the future in Washington politicians, none of whom was inspiring because it seemed that behind the bombast, the rhetoric, the promises, their major concern was their own power…

There were other citizens, those who tried to hold on to ideas and ideals still remembered from the sixties and early seventies, not just by recollecting but by acting. Indeed, all across the country there was a part of the public unmentioned in the media, ignored by the politicians – energetically active in thousands of local groups across the country. These organized groups were campaigning for environmental protection or women’s rights or decent health care … or housing for the homeless, or against exorbitant military spending.

This activism was unlike that of the sixties, when the surge of protest against race segregation and war became an overwhelming national force. It struggled uphill, against callous political leaders, trying to reach fellow Americans most of whom saw little hope in either the politics of voting or the politics of protest.

The presidency of Jimmy Carter, covering the years 1977 to 1980, seemed an attempt by one part of the Establishment, that represented in the Democrat party, to recapture a disillusioned citizenry. But Carter, despite a few gestures toward black people and the poor, despite talk of ‘human rights’ abroad, remained within the historical political boundaries of the American system, protecting corporate wealth and power, maintaining a huge military machine that drained the national wealth, allying the United States with right-wing tyrannies abroad.

Carter seemed to be the choice of that international group of powerful influence-wielders – the Trilateral Commission … (which) thought Carter was the right person for the 1976 election given that ‘the Water-gate plagued Republican party was a sure loser’… Carter’s job as President, from the point of view of the Establishment, was to halt the rushing disappointment of the American people with the government, with the economic system, with disastrous military adventures abroad… (See also for example: Byrd, 2004: Hightower, 2003: McCoy, 2003: Scott & Marshall, 1991)

While the political scenario in Venezuela is also dominated by two broadly allied groupings that overall has produced a type of bipartisan competition, in stark contrast to the political situation in the United States (where both major parties essentially represent the same elite interests) in Venezuela there are clear and fundamental differences in the ideological basis, policies and objectives of each broad alliance of political parties, interest groups and social sectors. On one side are those connected to, allied with or supporters of the governing United Socialist Party of Venezuela (Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela, PSUV) formed by Hugo Chavez, who taken together form a broad and diverse coalition that is vehemently opposed by an eclectic array of mostly US-backed and right-wing neoliberal opposition political parties and interest groups. In terms of the prevailing political and economic context in Venezuela as of 2012 (and still very relevant today) James Petras states:

On October 7th, Venezuelan voters will decide whether to support incumbent President Hugo Chávez or opposition candidate Henrique Capriles Radonski. The voters will choose between two polar opposite programs and social systems: Chávez calls for the expansion of public ownership of the means of production and consumption, an increase in social spending for welfare programs, greater popular participation in local decision-making, an independent foreign policy based on greater Latin American integration, increases in progressive taxation, the defense of free public health and educational programs and the defense of public ownership of oil production.

In contrast Capriles Radonski represents the (traditional political) parties and (economic) elite who support the privatization of public enterprises, oppose the existing public health and educational and social welfare programs and favour neoliberal policies designed to subsidize and expand the role and control of foreign and local private capital. While Capriles Radonski claims to be in favour of what he dubs “the Brazilian model” of free markets and social welfare, his political and social backers, in the past and present, are strong advocates of free trade agreements with the US, restrictions on social spending and regressive taxation.

Unlike the US, the Venezuelan voters have a choice and not an echo: two candidates representing distinct social classes, with divergent socio-political visions and international alignments. Chávez stands with Latin America, opposes US imperial intervention everywhere, is a staunch defender of self-determination and supporter of Latin American integration. Capriles Radonski is in favour of free trade agreements with the US, opposes regional integration, supports US intervention in the Middle East and is a diehard supporter of Israel.

In the run-up to the elections, as was predictable the entire US mass media has been saturated with anti-Chávez and pro-Capriles propaganda, predicting a victory or at least a close outcome for Washington’s protégé. The media and pundit predictions and propaganda are based entirely on selective citation of dubious polls and campaign commentaries; and worst of all there is a total lack of any serious discussion of the historical legacy and structural features that form the essential framework for this historic election…

A brief overview of left-wing political factions and social sectors

To the left of the extremely diverse and highly compartmentalized and polarized political spectrum that exists in Venezuelan society, numerous leftist political parties, factions and social movements have long criticized and complained about the adoption and implementation of many of the socialist government’s policies. Relevant topics that are hotly debated in this respect typically include that the government has been far too willing to compromise with the ‘oligarchs’ and the traditional ruling elites, or that provisions for worker representation and participation in the management of State-owned companies are grossly inadequate and ineffective in many cases. The long series of compromises and agreements that have been reached by the Venezuelan Government at different times with a variety of groups and sectors from the traditional economic elites has severely undermined it’s ‘revolutionary credentials’ in these circles and fed suspicions among some that the plight and hardships of the common people is a secondary concern to staying in power. In terms of this perspective, an article by Ryan Mallett-Outtrim (2016) summarizes and evaluates the main principles, objectives and alternatives associated with the respective arguments in favour of ‘deepening the Revolution’ or compromising with the government’s US-backed political and economic opponents.

Another emblematic topic that has generated frictions between the Venezuelan Government and one of the main social sectors that typically has strongly supported and defended the revolution led by Hugo Chavez since its inception (poor and historically marginalised and oppressed small-scale rural farmers, producer collectives and communities) is the implementation of agrarian reform and rural development strategies. For many years there has been a substantial and growing divergence between many of these rural communities and producer collectives and the Government: key issues in this context include the strategic objectives and effective implementation of the agrarian reform agenda, as well as the need for reliable and effective technical and logistical support for collective social and economic projects and value-added production in rural communities.

A major problem in this context is that there are still very powerful landlords and economic/ political elites in many regions who control or have established alliances with the provincial governments, bureaucracies and police contingents, and while they are not as frequent and systematic as in Colombia the selective assassination of social leaders in rural areas is not uncommon, often accompanied by simultaneous legal/ bureaucratic persecution, harassment and forced displacement of rural communities in circumstances that suggest the active collaboration of some police and other State officials.

Attitudes and opinions on the country’s relations with the US have of course also been extremely divisive and problematic. On the pretence of alleged concerns over democracy and human rights violations, the US imposed a series of strict financial sanctions against the State-owned oil company PDVSA in 2017, which was extended to include an export embargo in 2019 with additional secondary sanctions imposed in 2020 (including severe penalties for any company maintaining financial or commercial relations with Venezuela, measures that were rigorously enforced). Following the outbreak of the Russia-NATO war in Ukraine and the subsequent large reduction in available energy sources, the US Treasury authorized some limited waivers to the sanctions in 2022 (for Repsol, Eni and Chevron). This was followed by another six-month licence allowing limited production, investment and sales in the oil and gas sectors in Venezuela following a so-called electoral deal (pursuant to which the US purports to have the right to evaluate and ‘certify’ the legitimacy of the pending electoral process in Venezuela – begging the question, who will supervise and certify the pending elections in the US).

Consequently, amongst the chaotic and unpredictable dynamics and developments that typify relations between the US and Venezuela over the last twenty-five years, the Venezuelan Government and US oil giant Chevron have reactivated commercial relations and the development of several joint projects in the energy sector. Chevron has been present in Venezuela since 1923, and notwithstanding the prolonged disruption the company still has four joint ventures with PDSVA that are capable of producing up to 200,000 bpd.

From a critical leftist perspective, the only way this could be considered even remotely justified (given that among a long list of other hostile and destructive acts against Venezuela, several years ago the US arbitrarily expropriated all of the properties and assets of Venezuela’s State-owned CITGO, a US-based refinery and distributor with a network of retail outlets whose assets have been estimated at over $10 billion) is in the nature of creating a potential economic ‘hostage’ or captive (against the enormous losses incurred from the theft of the Venezuelan peoples’ assets in the US), as well as possibly creating some contradictory corporate interest group and lobbying pressures within the US that might provide some counter-weight to the enormous influence that Exxon Mobil and its major shareholders enjoy viz the Congress, the White House and the media.

In this context, while Chevron agreed to work together with the Venezuelan Government (however reluctantly) following former President Hugo Chavez’ strategic decision to nationalise most of the oil sector (maintaining however the option of joint ventures in which PDSVA had a majority interest and a substantial role in operational management), Exxon Mobil bitterly condemned the decision and has done everything possible to contest and disrupt the process of nationalisation (a grudge that was carried over into the Trump administration when Exxon CEO Rex Tillerson was appointed Secretary of State in 2017).

However, it should also be noted that – in a financial/ corporate variant replicating to some extent the ‘of, by and for the economic and political Elite’ two-party State described by Howard Zinn – just below the surface it turns out that Chevron Corporation’s major shareholders are Vanguard Group Inc. (8.6%), Blackrock Inc. (6.6%), State Street Corporation (6.6%), Berkshire Hathaway, Inc. (5.8%) and Morgan Stanley (1.8%). Almost exactly the same as Exxon Mobil, whose largest shareholders are Vanguard Group Inc. (approximately 9.8%), Blackrock Inc. (6.8%), State Street Corporation (5.3%) and FMR, LLC (3.7%). Hence, in any given situation where they appear to be rivals or competitors no matter which consortium gets the deal, the result is already in: Heads we win, tails you lose. To further confuse the matter, almost all of the major institutional shareholders in each company also has a substantial stake in most of the other major shareholders, overlapping and interlocking in such a way that it is impossible to identify a central nucleus, organization or group of people who exercise strategic control over the corporations (Fichtner et al, 2017: Edgar, 2018a). LINK

Viewed from this hard core revolutionary perspective, compounding the failure to prosecute many of the senior military officials and opposition political figures who have openly conspired with a hostile foreign power in repeated violent and destructive coup attempts since 2002, or to take decisive steps to substantially reduce the control that a small number of oligarchs still exercise over key economic sectors (which they have exploited to the full on numerous occasions to deepen the economic woes of the country and the scarcity of essential goods to thereby destabilize the government), the willingness of the Venezuelan Government to maintain discussions with the US at all is a grave affront to many given that the US and the UK have brazenly stolen many billions of dollars-worth of Venezuela’s sovereign funds and economic investments in those two countries, among their incessant efforts to subjugate the country or destroy it economically and socially in the attempt.

US efforts to overthrow the Venezuelan Government

With respect to this broader geopolitical context, the detailed and well-informed analysis by James Petras cited above also provides an overview of the background to as well as the main social, economic and political factors and factions involved in the early attempts by the US to overthrow the Chavez Government:

For nearly a quarter of a century prior to the Chavez election in 1998, Venezuela’s economy and society was in a tailspin, rife with corruption, record inflation, declining growth, rising debt, crime, poverty and unemployment.

Mass protests in the late-1980s and early-1990s led to the massacre of thousands of slum dwellers, a failed coup and mass disillusion with the bi-partisan political system. The petrol industry was privatized; oil wealth nurtured a business elite which shopped on Fifth Avenue, invested in Miami condos, patronized private clinics for face-lifts and breast jobs, and sent their children to private elite schools to ensure inter-generational continuity of power and privilege. Venezuela was a bastion of US power projections toward the Caribbean, Central and South America. Venezuela was socially polarized, but political power was monopolized by two or three parties who competed for the support of competing factions of the ruling elite and the US Embassy.

Economic pillage, social regression, political authoritarianism and corruption led to an electoral victory for Hugo Chávez in 1998 and a gradual change in public policy toward greater political accountability and institutional reforms which signaled a turn toward greater social equity.

The failed US backed military-business coup of April 2002 and the defeat of the oil executive lockout of December 2002 to February 2003 marked a decisive turning point in Venezuelan political and social history: the violent assault mobilized and radicalized millions of pro-democracy working class and slum dwellers, who in turn pressured Chávez to turn left. The defeat of the US-capitalist coup and lockout was the first of several popular victories which opened the door to vast social programs covering the housing, health, educational, and food needs of millions of Venezuelans.

The US and the Venezuelan elite suffered significant losses of strategic personnel in the military, trade union bureaucracy and oil industry as a result of their involvement in the illegal power grab. Capriles was an active leader in the coup, heading a gang of thugs that assaulted the Cuban embassy, and an active collaborator in the petrol lockout which temporarily paralyzed the entire economy.

The coup and lockout were followed by a US-funded referendum, which attempted to impeach Chávez, and was soundly trounced. The failures of the right strengthened the socialist tendencies in the government, weakened the elite’s opposition and sent the US on a mission to Colombia, ruled by narco-terrorist Álvaro Uribe, in search of a military ally to destabilize and overthrow the regime from outside. Border tensions increased, US bases multiplied to seven, and Colombian death squads crossed the border (to conduct sabotage operations and terrorize border communities in Venezuela)…

The transfer to Colombia of the main bases for the organization and preparation of covert hybrid warfare operations against Venezuela was rapidly consolidated and deepened over the following decade. Many readers no doubt automatically dismiss such claims and allegations as absurd and preposterous, completely unsubstantiated socialist/ communist (‘Castro-Chavista’, the local equivalent of ‘Kremlin-backed’) ‘talking points’ and propaganda. Nonetheless, before dismissing them out of hand, as a short introduction to some of the available information and evidence supporting the preceding affirmations a good starting point is the analysis written by James Petras noted previously explaining the political, economic and geopolitical dimensions of the presidential elections in Venezuela in 2012 (“Venezuelan Elections: A choice and not an echo”), another published by Venezuela Analysis several years later (by Ryan Mallett-Outtrim, 2016, “Revolutionise or Compromise?”), and two documentaries describing events during the openly US- and corporate media-backed failed 2002 military/ corporate coup attempt (“The Revolution will not be televised” produced by The Irish Film Board and YLE Teema, and “Anatomy of a Coup” produced by Journeyman productions).

A very short selection of other very well documented examples of the machinations of US subversion operations and regime change plots include the extraordinary short book “War is a Racket” written by US Marines Major General Smedley Butler (in the 1930s), the documentary produced by Bill Moyers in 1987 on the Iran-Contra scandal (“The Secret Government: Constitution in Crisis”), another documentary on the assassination of Patrice Lumumba (Michel Noll, “The execution of Patrice Lumumba”, from the Political Assassination Documentary series produced by News World). For a quick introduction to intensive and systemic ‘meddling’, subversion and institutionalised fraud and corruption within the United States, a good start would be a documentary that investigates “COINTELPRO: The FBI’s War on Black America” (by Maljack Productions) and another produced by Aaron Russo (America: From Freedom to Fascism).

Perhaps most disturbing of all is a document attributed to the US Southern Command which describes the available alternatives and military/ intelligence assets in and around Venezuela that could be called upon in an all-out attempt to overthrow the Venezuela Government. In 2018 a ‘top secret’ document entitled “Plan to Overthrow the Venezuelan Dictatorship ‘Masterstroke’” was disclosed by veteran Argentinian journalist Stella Calloni (Calloni, 2018). The document, dated the 23rd of February 2018, was attributed to the United States Southern Command (‘SouthCom’). Its publication generated considerable coverage and comment in the ‘alternative’ press in Latin America, however it received little or no mention in the ‘mainstream’ media (Edgar, 2018b). LINK

As with the ‘Protocols of Zion’, whether or not the document is authentic (as far as I know SouthCom has not denied its authenticity, and they would hardly acknowledge authorship of such a document), the report appears to provide a very accurate description of many developments related to the clearly demonstrated US obsession with and strategies for overthrowing the Venezuelan Government, apart from evidencing the authors’ considerable familiarity with US military and intelligence assets in the region.

The wide range of prospective contingency plans and alternatives canvassed in the document include an open military invasion together with the armed forces of as many of Venezuela’s neighbours as could be persuaded or obliged to participate (in particularly Brazil, Colombia, Panama, and Guyana), supported by paramilitary groups and other covert forces and groups either already present in or projected to be infiltrated into Venezuela and other countries throughout the region.

The report also appears to provide an accurate description of the immense scope and ruthlessness of the United States’ disruptive economic, social and political actions aimed at destabilizing and overthrowing the Venezuelan government, and anticipates the possibility of an even more dramatic escalation in intensity and scale. For instance, in order to undermine “the decadent popular support” for the Venezuelan Government: “Encouraging popular dissatisfaction by increasing scarcity and rise in price of the foodstuffs, medicines and other essential goods for the inhabitants. Making more harrowing and painful the scarcities of the main basic merchandises…” All this accompanied by a relentless media campaign blaming the Venezuelan Government and ‘the Dictator Nicolas Maduro’ in particular for the shortages of basic goods in the wider context of total economic collapse. Related activities and objectives would include:

“Fully obstructing imports… Appealing to domestic allies as well as other people inserted from abroad in the national scenario in order to generate protests, riots and insecurity, plunders, thefts, assaults and highjacking of vessels as well as other means of transportation with the intention of (provoking mass desertions and migration from Venezuela) through all borderlands and other possible ways, jeopardizing in such a way the National Security of neighbouring frontier nations. Causing victims and holding the Government responsible for them. Magnifying, in front of the world, the humanitarian crisis in the country…”

Also consistent with the stated intentions, plans and coordinated series of overt and covert military/ intelligence operations outlined in the document, around the same period the US staged several large-scale multilateral military exercises in the region (Dinucci, 2017). The threats and polemic emanating from Washington intensified dramatically after 2015 when then president Barack Obama promulgated an Executive Order “declaring a national emergency with respect to the unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States posed by the situation in Venezuela”.

The document also inadvertently acknowledges the importance of Venezuela to the ‘second war of independence’ in Latin America following the election of Hugo Chavez, leading to the consolidation of regional forms of cooperation that explicitly or implicitly rejected Washington’s ‘leadership’ and domination. In this respect, the report affirms with satisfaction that the recent “rebirth of democracy” (return to conservative, neoliberal, right-wing governments that unquestioningly support Washington’s policies) has halted the trend “in which radical populism was intended to take over” South America (Argentina, Brazil and Ecuador are cited as examples of the resurrection of democracy).

Also reflecting the geopolitical significance of other related developments in the region initiated by Hugo Chavez, the report includes as part of the ‘Information Strategy’ a mass media campaign proclaiming the failure of regional “mechanisms of integration created by the regimens of Cuba and Venezuela, specially the ALBA and PETROCARIBE”, along with “strengthening the image of the OAS”. In this wider context, the document expresses the expectation that “overthrowing the Venezuelan Dictatorship will surely mean a continental turning point” in terms of returning the entire region to a strategic alignment with and political and economic subordination to the US.

In case the economic and social turmoil and political violence generated within Venezuela itself should prove insufficient, the document advocates “preparing the involvement of allied forces” to support a prospective rebellion launched by Venezuelan army officers willing to collaborate with the scheme. Related measures would include:

“Getting the support and cooperation of the allied authorities of friendly countries (Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, Panama and Guyana)…

Organizing the provisioning, relief of troops, medical and logistical support from Panama. Making good use of the facilities of electronic surveillance and signals intelligence, the hospitals and its deployed endowments in Darién, the equipped airdromes for the Colombian Plan, as well as the landing fields of the old-time military bases of Howard and Albrook…

(Existing weapons stockpiles would be greatly augmented including with heavy weapons as a prelude to) developing the military operation under international flag… Binding Brazil, Argentina, Colombia and Panama to the contribution of greater number of troops, to make use of their geographic proximity and experience in operations in forest regions. Strengthening their international coalition with the presence of combat units from the United States of America and the other named countries, under the command of a Joint General Staff led by the USA…

Using the facilities at Panamanian territory for the rear guard and the capacities of Argentina for the securing of the ports and the maritime positions…

Leaning on Brazil and Guyana to make use of the migratory situation that we intend to encourage in the border with Guyana…

Coordinating the support to Colombia, Brazil, Guyana, Aruba, Curacao, Trinidad and Tobago and other States in front of the flow of Venezuelan immigrants in the event of the crisis…

Continuing setting fire to the common frontier with Colombia. Multiplying the traffic of fuel and other goods. The movement of paramilitaries, armed raids and drug trafficking. Provoking armed incidents with the Venezuelan frontier security forces… Recruiting paramilitaries mainly in the campsites of refugees in Cúcuta, La Guajira and the north of Santander, areas largely populated by Colombian citizens who emigrated to Venezuela and now return, run away from the regimen to intensify the destabilizing activities in the common frontier between the two countries. Making use of the empty space left by the FARC, the belligerency of the ELN and the activities in the area of the Gulf Clan…”