Written by Daniel Edgar exclusively for SouthFront

Previous articles have examined the social and environmental impacts of two major mining projects in Colombia owned and operated by Australian-domiciled companies (Part I – https://southfront.org/colombia-multinationals-and-indigenous-people-part-i-the-wayuu/ and Part II – https://southfront.org/colombia-multinationals-and-indigenous-people-part-ii-the-zenu/). This article reviews recent developments with respect to the mining projects and the regions in which they are located.

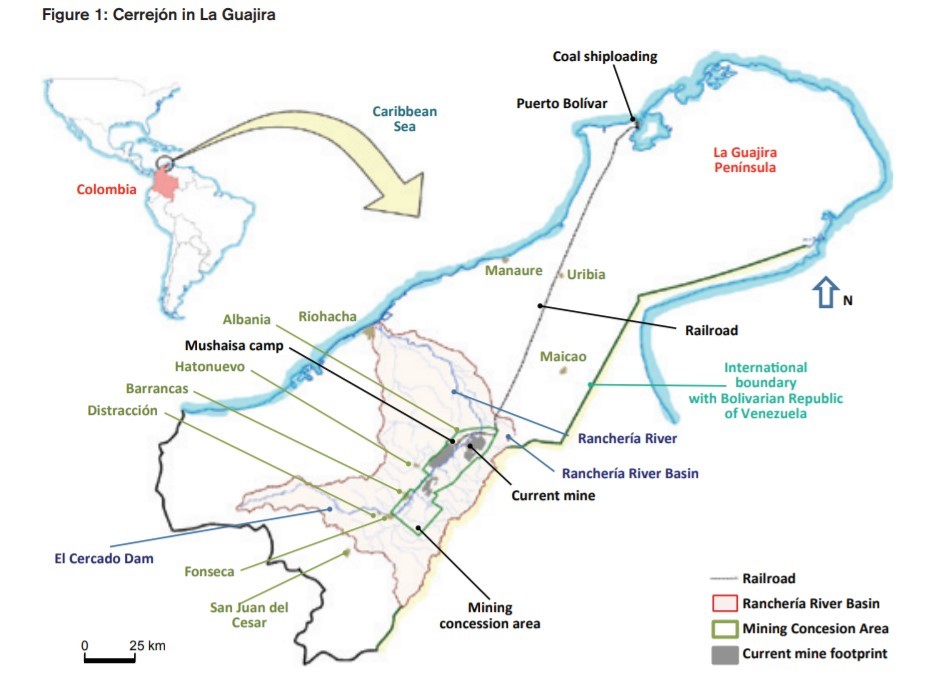

The Cerro Matoso project is located in the territory of the Zenú people in the central-northern province of Cordoba, and the Cerrejon project is located in the territory of the Wayúu people in La Guajira in the far north-east of Colombia, near the border with Venezuela (the ancestral territory of the Wayúu is divided by the international border and generally they have dual-nationality in recognition of this). While the two mining projects have provided a significant portion of Colombian export earnings over the last thirty years, the predominantly Indigenous communities that live in the areas affected by the mining projects have suffered from a severe deterioration in their living conditions and the environment as well as the quality and quantity of their agricultural and natural resources, including the contamination and depletion of local water sources. Both regions have also been heavily affected by the social and armed conflict that continues to ravage Colombia, exacerbated in each instance by the activities associated with the mining projects and the resulting loss and pollution of substantial portions of their territory.

BHP Billiton has been heavily involved in both mining projects over the last two decades: El Cerrejon in La Guajira, an enormous open-cut coal mine (which BHP Billiton has jointly owned since 2000 with Anglo-American and Glencore/ Xstrata), and Cerro Matoso in Córdoba, another enormous mining project that was acquired around the same time and which also has a large smelting complex to produce ferronickel. BHP Billiton owned Cerro Matoso outright until 2015 when it was transferred to the Perth-based company South 32 (given that the same four shareholders – namely JP Morgan, HSBC, Citigroup and ‘National Nominees’ – own a controlling interest in both BHP Billiton and South 32, the transaction cannot properly be referred to as an arm’s length sale and purchase). Both projects were owned by the Colombian State until they were sold to comply with economic programs developed by the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

After reviewing some of the most significant developments that have occurred there is more detailed information at the end of the article for those who may be interested, consisting of translations from Spanish of news reports and other primary and secondary sources (in each instance the translations have been done by the google translator with subsequent editing by the author).

In 2017 two landmark decisions of the Constitutional Court (Sentence T-302/17 and Sentence 733/17) recognised the social and environmental catastrophes that the communities living around both mining projects are experiencing and held that several of their fundamental constitutional rights have been violated (such as the rights to life, access to potable water and food, due process and prior informed consent).

The decisions by the Constitutional Court during 2017 (as well as several other related judgments by the Constitutional Court and the two other superior courts of the Colombian judicial system – the Supreme Court and the Council of State – over the preceding years) are of historic significance. In several judgments the Court has held that mining operations have been important contributing factors to the dire conditions afflicting communities in each region face (including Sentence T-256 of 2015 in the case of Cerrejon and Sentence T-733 of 2017 in the case of Cerro Matoso) and that the mining companies share responsibility with the State for ensuring that the rights of residents in each region are respected.

Although the two judgments in 2017 constituted major victories for the communities of each region in the defence of their rights, subsequent developments have taken very different courses. There is however one constant: many years after the first judgments purporting to guarantee and protect the rights of the communities in each region, the relevant State and corporate bureaucracies continue to demonstrate an attitude of utter contempt of court, and have made no significant progress towards rectifying the persistent and grave violations of the constitutional rights of the residents of the communities affected. Notwithstanding their capacity to establish procedures to monitor compliance with their orders, the Courts have been powerless to hold the authorities accountable.

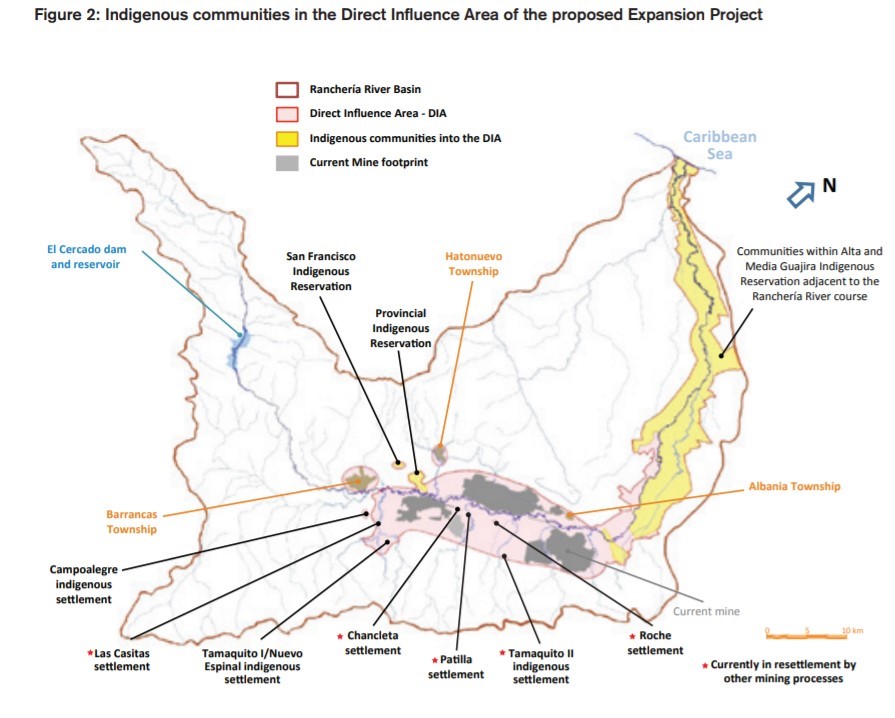

Cerrejón and the Wayúu people in La Guajira

In the case of Cerrejon and Wayúu communities in the region, the legal judgments have addressed two points. One is the fundamental right of the Wayúu communities to access to potable water, food, health and associated essential goods and services, rights that are guaranteed by the Colombian Constitution. The other is the impacts of activities associated with the Cerrejon mining project in specific areas: the court cases associated with this typically involve two aspects, alterations to the landscape that deprive communities of access to local water sources and contaminate those that remain (including a judgment by the Council of State proclaimed on the 13th of October 2016), and the obligation to relocate communities that have been displaced by mining operations (including Sentence 256/15 proclaimed by the Constitutional Court on the 5th of May 2015). Although all of these elements are integrally linked, legal technicalities usually make it extremely difficult to include the companies that own Cerrejon in proceedings demanding respect and protection for constitutional rights and obligations.

The following figures (taken from a study completed by Cerrejon in 2011 in anticipation of a substantial increase in coal production – the title of the report is Iiwo’uyaa: Seeding the Future – Summary of the Iiwo’uyaa Expansion Project for Stakeholders) demonstrates the scale of the project in regional terms, sprawling over many hundreds if not thousands of square kilometres that have in many instances been forcibly expropriated from the communities in the region.

The consequences of the inadequacy of regional infrastructure and the provision of essential goods and services have been devastating, exacerbated by successive stages of expansion of the mining project and the resulting loss of land, water supplies and natural resources available to communities in the region. Literally thousands of Wayúu children have died from malnutrition and preventable diseases, primarily as a result of the lack of potable water (4,770 over the last eight years to be exact, according to evidence proffered to a public hearing concerning implementation of Sentence T-302/17), apart from the many thousands that are severely affected albeit not to the point of death. Yet.

The public hearing to review progress in the implementation of the Court’s orders in Sentence T-302/17 was held early in October 2018, attended by a magistrate of the Constitutional Court together with other senior public officials,. A news report describing the proceedings, which found little change in the situation of the communities involved in the case, is included below.

In the same month as the public hearing into the (non)implementation of Sentence T-302/17 was held, a separate judgment by the Constitutional Court (T-415/18, proclaimed on the 10th of October) declared that the ‘state of inconstitutionality’ found in the earlier judgments (namely, that State authorities and Cerrejon were and are gravely violating the constitutional rights of communities to access to potable water, food, and other essential goods and services, as well as the rights to due process, equality and prior informed consent) also affects another five communities in the region.

The most recent judgment by the Constitutional Court (T-415/18) also noted that the relevant authorities should coordinate their responses to the multiple court orders in order to work towards an integral, efficient and effective strategy to address the supply of essential goods and services throughout the region. The companies (BHP Billiton, Anglo-American and Glencore/ Xstrata) must acknowledge a substantial part of this responsibility, given that the mining project dominates the region and has dramatically transformed the landscape over the last thirty years, substantially reducing and polluting the local water sources and other resources available to residents as the companies’ owners have extracted many billions of dollars of profits from the mining project.

This need for strategic and integrated planning was a central element of the judgment proclaimed by the Supreme Court on the 31st of July 2016, in which it ordered the Presidential Office to: “Design, coordinate and execute an efficient and effective plan that provides an integral and definitive solution to the difficulties of malnutrition, health and access to potable water confronting the Wayúu children.” It also ordered that a report be submitted to the local tribunal each month on actions taken to ensure implementation of the plan. This remains the most urgent and imperative element if a long term solution is to be elaborated.

While the Colombian State has primary constitutional responsibility for this, the companies must fully cooperate with all levels of the Colombian State (national, provincial and municipal) and, most importantly, with the full participation and prior informed consent of the affected communities, to implement the orders of the Constitutional Court in Judgment T-302 of 2017 in good faith. This includes the elaboration of immediate and long term strategies to remedy the catastrophic social and environmental conditions the communities in the region face, integrating the measures with the orders of the courts in other judgments and the needs of all residents and communities in the region more generally.

Despite at least four judgments by the highest courts in the land demanding immediate action (most of which have been partly founded on previous actions before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights which has also ordered that the Colombian State take immediate action to remedy the situation on several occasions), the plight of the communities in the region has not registered notable improvement. The company continues to enjoy its privileged access to the water that is available in the region and the responsible government agencies and politicians still have not made meaningful progress towards resolving the lack of essential infrastructure, goods and services.

It appears that nothing will change until the company’s access to water and other essential services is also cut off, and a swathe of ‘public servants’ are dismissed (or jailed in the event corruption or other malfeasance is found – arguably abject and gross negligence and dereliction of duty, not to mention utter contempt of court for at least four years, could suffice in at least some instances given that so many lives have been, and continue to be, destroyed) and replaced by competent people who are committed to serving the Colombian people and complying with their constitutional duties.

In this vein, but also in recognition of the urgency of the conditions facing communities in the region, a measure that must be taken immediately is a substantial reduction in the amount of water used by Cerrejon until the regional water supply shortage has been completely resolved. While the company uses millions of litres of water in its daily operations on a priority basis and with very favourable terms (including unlimited access to water to irrigate the lawns in the enclave community where corporate executives and administrators live) many communities in the region have no water supply infrastructure at all (at the same time as the mining project has systematically eliminated their traditional water sources).

More generally, the situation in La Guajira is indicative of the lamentable condition of the provision of essential gods and services throughout the country. In many regions water supply is intermittent, arriving once or twice a week by way of dilapidated aqueducts, and the water is heavily polluted. Moreover, the water cannot be accessed unless the residents have their own water pump. However, this is great for the businesses of local economic, administrative and political elites, as residents have to pay exorbitant amounts for every drop of drinking water. There is no apparent solution in the absence of a national institute responsible for developing and coordinating an integral strategy across the country and facilitating access to the necessary planning, technology and capital in each region. Even in municipalities where the local government has the inclination to seek improvements, it is simply beyond their capacity.

Cerro Matoso and the Zenú people in Córdoba

With respect to developments in the region where Cerro Matoso is located, the company successfully appealed the 2017 judgment (proclaimed by a Chamber of Revision of the Constitutional Court consisting of three members) before the Full Court (consisting of nine members, though two magistrates precluded themselves from hearing the case – news reports did not state why the magistrates considered themselves incapable of hearing the case). The resulting pronouncement (Auto 616/18 proclaimed on the 20th of September 2018, translated below) is a most unsatisfactory exercise in judicial analysis and reasoning (two magistrates dissented), suggesting that factors other than the merits of the respective legal arguments and social justice were decisive (a result anticipated by the claimants, as noted in one of the news articles translated below). The comments of the dissenting magistrates, included below, succinctly outline the deficiencies in the reasoning adopted by the majority.

In its 2015 annual report BHP Billiton described the ferronickel complex at Cerro Matoso as the lowest-cost producer of ferronickel in the world. It is now an indisputable fact that this has largely been at the cost of the local communities to whom all social and environmental costs have been externalised. That the mining and smelting operations at Cerro Matoso have directly caused social and environmental devastation in the region (a fact that the company has consistently and vehemently denied) was recently recognised and documented by a detailed medical study ordered by the Constitutional Court in Judgment T-733 of 2017 (a news report of which is translated below). Nonetheless, in the appeal a majority of the Court overruled the previous detailed consideration of the medical study, blithely accepting the argument that the study didn’t conclusively prove that the mining and smelting operations were a direct cause of the drastic deterioration in environmental and health conditions that have occurred in the region since the mining project commenced operations.

It is imperative that BHP Billiton doesn’t attempt to use the supposed ‘sale’ of Cerro Matoso to South 32 as a pretext to deny legal and financial responsibility for the ownership and management of the project over the last two decades, when most of the damage was inflicted on the communities located around the mine (and, conversely, that South 32 doesn’t use its recent ‘acquisition’ of the project as a pretext to deny responsibility for reparations and the prevention, or at least mitigation, of harmful impacts in the future).

The differentiated impact of the armed conflict in the regions

Another aspect of the direct and indirect social impacts of the mining projects is the horrific violence that has been unleashed against community leaders in the regions where the mining projects are located over the last three decades. A ferocious and unrelenting campaign of terror and social control has been waged against community leaders in both regions (in the vicinity of Cerrejon and Cerro Matoso respectively), in particular against those leaders that have confronted Cerro Matoso and Cerejon and sought justice for their communities (over thirty social leaders from the communities around Cerro Matoso alone have been assassinated in a ruthless and systematic campaign of terror, plunder and social control).

The violence and attacks intensified when community leaders started trying to obtain information regarding the legal ownership of relevant properties as well as economic and environmental details about the mining projects and their impacts. Irrespective of whether the management of BHP Billiton in particular (and more recently South 32) has directly or indirectly collaborated with the perpetrators of these attacks or not, the company (and the four shareholders mentioned above in particular) has been the primary beneficiary of all of these developments and must recognise its responsibility and commit itself to clarifying and rectifying the situation.

The companies must clearly identify who are the executives that are responsible for the operations in Colombia, and the most senior executives must assume ultimate responsibility for the corporate strategies in each instance. Further, they must explain how they have managed to operate with so little difficulty in two regions where the local communities have been terrorised and decimated by the illegal armed groups that dominate each region. Did they reach an agreement with the armed groups so that operations could continue?

Or have the companies actively collaborated with the armed groups and if so to what extent – the targeted and systematic terror campaign waged against local communities demanding adequate responses from the companies and State authorities strongly suggests tolerance by the companies if not some degree of complicity in at least some of the many attacks and assassinations that have occurred. Not only have the armed groups (including in at least some instances members of the ‘public security services’) not disrupted corporate production; they have actively deployed against opponents of (or impediments to) the mining projects.

What have the companies done to denounce these attacks and protect the lives and welfare of the people living in these communities? Are they prepared to participate in the ongoing Truth and Justice Commissions in Colombia to clarify what has been happening in these regions, how the violence has affected them, and what strategies they have employed that enabled them to continue production largely unaffected by the turmoil and rampant violence?

The following are a selection of news reports concerning the developments reviewed above.

Reports Concerning Cerro Matoso (Córdoba)

Laura Neira Marciales, “Corte Constitucional tumbó reparación de Cerro Matoso a 3.000 personas” (Constitutional Court overruled reparation of Cerro Matoso to 3,000 people), 20th of September 2018, La República

“In December of last year the Fifth Chamber of Revision of the Constitutional Court imposed a sentence against Cerro Matoso, according to which the company must compensate the communities in the province of Cordoba affected by its activity, as well as renew its environmental licence.

Yesterday, the Full Chamber of the tribunal conceded the petition for annulment proposed by the mining company against Sentence T-733 of 2017.

With this determination, the Court left without legal foundation the compensation that the mining company was responsible for, which had been estimated at US$400 million.

The vote which was five votes in favour and two against, only included seven magistrates, as Magistrate Gloria Ortiz and Magistrate Alejandro Linares declared themselves impeded from hearing the case.

The company Cerro Matoso presented a petition for annulment against the sentence, arguing that the Court breached its right to due process. Moreover, it added that the chamber of revision that proclaimed the sentence failed to recognize a decision of 1995 that stipulated other rules for the determination of this type of compensation.

Another argument presented by the mining company was that there were no scientific studies that could prove that the illnesses affecting the population were caused by its mining activity.

Thus, the judgment was proclaimed despite the fact that the Court had previously stated: “there is a delicate situation of public health in the zone, of grave skin, lung and eye illnesses.”

The mining company refused to create a Special Fund for Ethno-Development with which the communities of Cordoba would be rehabilitated, however the Court demanded that the company provide integral and permanent health care services to the inhabitants of Puerto Libertador and Montelibano, which are located close to the mine in Cordoba.

Sentence T-733, decided by the Court in December (of 2017) and whose presenting Magistrate was Alberto Rojas Ríos, determined that the Zenú communities of Alto San Jorge should be compensated by the company Cerro Matoso.

Within the original sentence the ancestral relationship that the Zenú people have with the land exploited by the company was recognized. The maximum tribunal recognized that the rights of these communities were violated and established something exceptional in a sentence of revision: it recognized a right to monetary compensation for the communities…”

National Editing Board (Redacción Nacional), “Corte Constitucional tumbó fallo en contra de Cerro Matoso” (Constitutional Court overruled judgment against Cerro Matoso), El Nuevo Siglo, 21st of September 2018

“In resolving a petition for annulment filed by the mining company Cerro Matoso S.A., controlled by the multinational BHP Billiton (sic – the project was sold to South 32 several years ago), the Constitutional Court overruled its own decision made in December (of 2017).

The Court had ordered Cerro Matoso, through sentence T-733 of 2017 (presided by the Honourable Magistrate Alberto Rojas), to compensate the Indigenous communities of Alto Zenú in Córdoba, whose health has been affected by the ferronickel exploitation.

The mining company argued that the Court did not rely on technical and scientific criteria for the ruling, a position that was accepted by the magistrates by a vote of five against two.

According to Cerro Matoso, there are no scientific studies that prove that the illnesses of the population are caused by the mining activity.

The plaintiffs demanded reparations of $400 million, on behalf of the 3,400 people who live in the affected communities…

The order to suspend extractive activities in the event that the first judgment was not complied with was consequently also left without a legal basis.

“The Court found that the decision violated legal precedents in terms of the requirements for an order for compensation for damages in the abstract and also, that the decision lacked a proper basis regarding the creation of the fund (for reparations) and the sanction of suspension of activities”, the Court reported.

Also, the Court accepted the mining company’s reasoning for its refusal to create a Special Ethno-Development Fund with which they would rehabilitate the communities of Córdoba.

However, the Court demanded that the company provide integral and permanent health services to the inhabitants of Puerto Libertador and Montelíbano, adjacent to the mine in Córdoba…

The Court did not overrule the original decision with respect to the protection of the fundamental right of prior consultation, pursuant to which the Office of Prior Consultation of the Ministry of the Interior will have a period of one year to consult eight communities in order to establish measures for environmental prevention, mitigation and compensation.

Once the consultation process is in place, the multinational must initiate the process for obtaining a new environmental licence and must include the instruments and measures necessary to address health and environmental impacts of the operations.

Finally, criteria for protecting the environment and guaranteeing the health of people living in nearby towns must be established.

Anticipating this outcome, the representatives of the eight communities have decided to go to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) seeking a declaration requiring the Colombian State to adopt precautionary measures to prevent irreparable damage to life, personal integrity and private property.

“We make this request considering the various rumours about the lobbying ability of executives, lawyers and spokespersons of the multinational before the Constitutional Court, which is currently studying a request for partial annulment”, the representatives said in a press release.

The letter demanded that the decision of sentence T-733 of 2017 be maintained in its entirety and that none of the orders contained in the operative part of the judgment be annulled.”

Judicial Editors, “Las razones de la Corte para tumbar la reparación en caso Cerro Matoso”, 21st of September 2018, El Tiempo, Redacción Justicia

“According to the new decision of the magistrates, the previous ruling had violated the right to due process because it ignored a constitutional precedent that determines under which conditions compensation for damages can be ordered…

The Court said in the December decision that with the operation, which has as its epicentre the Zenú territory of Alto San Jorge, and the construction of a furnace 185 meters long and six in diameter (of the largest in the world), “the inhabitants of the municipalities near the mine began to notice a drastic change in the environment and felt the negative impacts on their territory, the environment, their water sources and their health”, the decision reads.

Cerro Matoso must renew its licence

Cerro Matoso will also have to renew its license in four months and comply with all the environmental requirements in order to continue operating the ferronickel mine it has in Córdoba for 36 years, the fourth largest of its kind in the world.

For the Court, it is clear that Cerro Matoso must update its environmental license. In 2012, when the contract was renewed – which allows it to operate the mine until the year 2044 -, it continued to operate with the same environmental licence that it has had for 30 years and that ignores the changes invoked by the Constitution of 1991 and subsequent regulations.

The new licence that Cerro Matoso must process, must make a prior consultation process, include measures to mitigate their environmental impacts, and guarantee the health of the affected populations…”

AUTO 616 of 2018: Declaration by the Constitutional Court (unofficial translation by the author)

“The Full Chamber of the Constitutional Court resolved the applications for partial annulment presented by the company Cerro Matoso S.A. and the Colombian Mining Association against Sentence T-733 of 2017, on the basis that the judgment violates the fundamental right to due process.

In studying the request for annulment, the Court reiterated the jurisprudential rules that determine the formal and material requirements of annulment against the orders that it declares and, based on those requirements: (i) rejected the request raised by the Colombian Mining Association, for lacking legitimacy, and (ii) studied the request of Cerro Matoso SA, in relation to which it decided:

- To reject the argument against the seventh order of the Court, according to which the company Cerro Matoso S.A. must provide integral and permanent attention to the affected community, since the request does not comply with the requirements for annulment.

- To declare the annulment of the eighth order, according to which the company was sentenced in the abstract to the payment of damages for the harm caused to the members of the plaintiff communities, as the order violates the requirement of due process. The aforementioned order ignored the relevant constitutional precedents in matters of compensation for damage caused by a defendant, given that, in accordance with Article 86 of the Constitution and the case law, the essential purpose of this class of judicial remedy is the immediate protection of fundamental constitutional rights through a preferential and summary procedure the procedure for which cannot last more than ten (10) days.

In this regard, the Court reiterated the guidelines established in judgment SU-254 of 2013, in which the Court noted that the ancillary and exceptional nature of compensation in the abstract, referred to in Article 25 of Decree 2591 of 1991, requires the application of the following rules: (a) the remedy does not have the character of a patrimonial or compensatory purpose, but rather the purpose is the protection of fundamental rights; (b) its origin is conditional upon compliance with the ancillary requirement, namely that there is no other judicial means to obtain compensation for the harm caused; (c) there must be a clear violation of or threat to the right and a direct relationship between the right and the legal action; (d) the measure must be necessary to ensure the effective enjoyment of the right that has been violated; (e) the defendant’s right of defence must be ensured; (f) compensation via legal action may cover the damage caused by the defendant; and (g) the court must specify the damage or prejudice suffered, the act that caused the damage, the reason why compensation is necessary to guarantee the effective enjoyment of the right that has been violated, the causal link between the defendant’s actions and the damage caused, as well as the criteria for the assessment of compensation carried out by the trial judge.

- Finally, to declare the annulment of the ninth and tenth orders of the Court, as due to the partial annulment of the sentence the remaining orders lack sufficient basis to instigate the creation of the ethno-reparation fund and to impose consequences for non-compliance not provided for in Decree 2591 of 1991, respectively.

Magistrate Diana Fajardo Rivera and Magistrate Alberto Rojas Ríos partially reserved their vote. In its conception and purpose, the nature of the annulment proceeding prevents the Plenary Chamber from reopening the debate to address substantive issues that were resolved in the judgment that is the subject of the petition for annulment. Moreover, the exceptional nature of the proceeding cannot be used as an additional instance to challenge the aspects of the sentence and orders of the Court that are disputed. The decision that motivates this as a ground for appeal ignores the argumentative demands that must be assumed by a person seeking to challenge a decision of this court; an appeal based on these grounds contravenes the authority that each chamber of the Court has to interpret the law (Decree 2591 of 1991) and the relevant precedents, always preferring an interpretation of the law that favours the protection of the rights of vulnerable persons and groups; and, finally, the grounds on which the appeal is based would deprive the affected peoples of the protection granted by the orders declared by the Seventh Chamber in terms of their health, customs, identity and quality of life.

Additionally, if – in the interest of discussion – it was accepted that there were defects with regard to the orders and the remedies declared by the Constitutional Court in Sentence T-733 of 2017 and not with the grounds and reasoning of the decision in itself – that is, the legal correctness and validity of the sentence proclaimed – what corresponds to the Court would be to initiate a dialogue with the correspondent parties in this respect, which could even lead to the modification or precision of the orders issued (in accordance with T-086 of 2003 and Article 27 of Decree 2591 of 1991).

In this instance, Magistrate Fajardo and Magistrate Rojas dissented with the annulment of the eighth, ninth and tenth orders of the sentence.

Regarding the eighth order (condemnation in the abstract), the dissenting magistrates stated that there was no contravention of the precedent contained in the sentence SU-254 of 2013, since in that case the ruling was rejected in the abstract for the families that had been forcibly displaced due to the existence of other means of administrative reparation envisaged in Law 1448. In this instance, the sentence and orders of the Court in Sentence T-733 of 2017 examined the lack of suitable and effective mechanisms to obtain such recognition and compensation.

Regarding the annulment of the ninth order due to a lack of legal grounds, Magistrates Fajardo and Rojas stated that Sentence T-733 of 2017 did justify the creation and operation of the Special Ethno-development Fund. A whole section of the judgment was devoted to explaining “the fundamental right to prior consultation of ethnic communities and the right to ethno-reparation,” and applied the jurisprudential rules established in sentences T-652 of 1998, T-693 of 2011 and T-969 of 2014. In addition, the decisions and doctrines proclaimed by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights were taken into account in the reasoning of the decision.

Finally, with regard to the annulment of the tenth order, their Honours stated that the decision of the Seventh Chamber of the Constitutional Court amply justified the power to suspend the mining activities in the face of any further breach of the orders contained in the operative part of judgment T-733 of 2017. Specifically, it was detailed that, under the terms of Decree 2591 of 1991, it was up to the judge at first instance to adopt the aforementioned suspension, only if the company failed to comply with the orders made in the judgment and extended its action indefinitely, to ensure compliance with the stated orders and remedies.

Finally, in the opinion of the dissenting Magistrates, it is not acceptable to void validly issued orders issued by the Review Chambers, based on grounds that were not invoked by the petitioner in the original proceedings, as was the case with the follow-up order issued to the judge of first instance and, in particular, with the decision regarding collective reparation. In short, the force of judicial determinations and respect for legal certainty are affected when judgments that are not arbitrary or contrary to law are annulled, even if they may be debatable. Especially when they protect the rights of the most vulnerable, as the judgment T-733 of 2017 did.”

Oscar Guesgán Serpa, 2017, “El dictamen de medicina legal en el caso Cerro Matoso” (The findings of the legal medicine report in the Cerro Matoso case), El Espectador, 11th of March 2017

“The medical experts identified, among 1,147 people studied, that more than 20% suffer from respiratory conditions. It could be considered a public health problem. According to Cerro Matoso, the study is not conclusive and leaves doubts about the results, as prior reports were not taken into account.

As of 2017, 38 years have passed since President Julio César Turbay granted the first concession for the exploitation of nickel at Montelíbano, Córdoba. And the mining project will continue for 27 more years. Colombia has received, as a result of royalties and taxes, $8.9 billion from Cerro Matoso during the last three decades, and the mine is the largest in South America.

In the midst of fluctuations and changes in the market, production has been maintained. It amounted to 36 thousand tons last year, but the company reported losses of US $70 million two years ago and according to the declarations of the company’s managers the situation is complicated. The investor, the Australian company South32, has some concerns about what is happening on this side of the world.

But the problem with which this article is concerned goes much deeper and is common throughout the world: what is the impact of mining activity, nickel exploitation specifically, on the health of human beings.

At the same time that Cerro Matoso has been trying to maintain the viability of the project, the Indigenous communities affected by the mining operations have dedicated themselves to asking for the exploitation to stop, because it causes dermatitis, loss of vision, genetic diseases, physical deformations, sterility, among other illnesses.

After almost four decades of nickel exploitation, Colombians do not know the health effects of the mineral. Meanwhile, the Zenú people, who have inhabited this area since pre-Hispanic times, have struggled simply to avoid being killed, as Israel Aguilar, the chief of the Zenú territory of Alto San Jorge, warned three years ago.

Two legal proceedings, alleging ongoing violations of the fundamental rights to health, a healthy environment and prior consultation and informed consent, were the alternatives chosen by the community to confront the company. The historical relationship between these two actors has been conflictive and there is no middle ground.

In the midst of the process, and at the request of Cerro Matoso, the Constitutional Court requested the Institute of Legal Medicine to conduct a technical study that would determine if the mining activity was the cause of the illnesses afflicting the Indigenous people and people of African descent living in the surrounding areas.

Despite the delays of the institute in charge of the study, which requested two extensions, it recently delivered the results to the court. El Espectador had exclusive access to one of the most awaited documents in the last 30 years by the mining sector, as well as by environmentalists, scientists and the community itself.

The investigation was conducted in Montelíbano, Puerto Libertador and San José de Uré, all parts of the area affected by the mine. The study was carried out on 1,147 people and included clinical examinations, photographic images, radiographic images and biological samples. The objective was to establish what illnesses people suffer and what is causing them.

It was not an easy task, as a variety of factors can negatively impact the health of the inhabitants of the area. And it is difficult to attribute the illnesses to a single cause, according to Legal Medicine. Also, the fact that there are no communities with which a comparison could be made complicated the task.

According to the document signed by Martha Elena Pataquiva and Sandra Lucía Moreno, both officers of Legal Medicine, “in 24.41% of the cases (280) there were signs of irritation of the upper airway and the conjunctiva of the eye, with a greater amount of the residents with these symptoms located in Puente Uré”.

This refers to irritation in the nostrils, mouth, pharynx and larynx, as well as in some membranes that cover the eyes. The scientific literature on the subject has established that nickel enters the human body mainly through the lungs, the gastrointestinal tract and the skin. The report says that the clinical results of industry workers include “rhinitis, sinusitis, perforations of the nasal septum and asthma.”

Meanwhile, another of the problems associated with contact with nickel is dermatological diseases. One of the findings of the Legal Medicine study is that in 41.32% of the cases (474) dermatological conditions were found, with more symptoms in the town of Pueblo Flecha which is located near the Cerro Matoso mine.

The institute also warned that there is a risk of a tuberculosis epidemic due to poor hygiene and sanitary conditions.

The importance of this document is that it is the first to give clues about the possible links between the exploitation of nickel and the diseases mentioned. However, it fails to establish if there are other environmental factors that generate them. The reactions described in the report could also be the result of poor water treatment in the absence of an aqueduct, cigarette consumption, or other environmental factors that were not identified due to the nature of the study…

Finally, Legal Medicine was able to establish that there could be a relationship between the mine and the illnesses of those who live near it. “It is striking that the higher prevalence of both dermatological manifestations and manifestations of irritation in the upper airway occurs in a greater proportion in the populations of Pueblo Flecha, Puerto Colombia and Torno Rojo. It is for this reason that an analytical approach was used to determine if the distance to the mine is indirectly related to the presentation of clinical manifestations, observing that both the manifestations of irritation in the airway and the dermatological manifestations occur more frequently in the people located near the mine”, concludes the document.

The president of Cerro Matoso, Ricardo Gaviria, says that “the document is not conclusive and there are still questions that have not been answered. In this process there is a series of tests that the Court has to complete before proclaiming a judgment in this regard. What is clear in the report and in a report from the Ministry of Health is that there is nothing conclusive that says that there is a causal relationship between mining operations and the effects that were found in the people studied”.

The company raised several concerns to Legal Medicine, including one related to the verification of previous environmental reports that showed the presence of soluble nickel (in the ground), which could explain the presence of the mineral in the rivers and in the air that the inhabitants of the area breathe. This would make the nickel levels in the blood and urine similar, but it did not happen this way.

Regarding this, the study found that nickel levels in the blood reached 10.53 mcg / l, while in the urine it reached 27.36 mcg / l. These, the same researchers acknowledge, are high levels, even compared with the results of other studies done internationally in workers with chronic exposure to nickel.

Everything indicates that there may have been faults in the processing of the sampling material or the possibility of contamination of the samples due to environmental factors in the field.

The document requested by the Constitutional Court is the first study that has been carried out in Colombia on this matter. The organization took the trouble to consolidate the international scientific literature, which tends to support the communities about the effects that constant contact with nickel can generate, either by working directly with it or by living nearby.

Gaviria said that soon another study will be carried out that will take between two and three years to complete and will cost that more than US $2 million. This work will not only consider clinical aspects, but also environmental factors, which is precisely one of the recommendations made by the Institute for Legal Medicine…”

Reports concerning El Cerrejón (La Guajira)

Libardo Muñoz, “¡4.770 niños wayuu muertos de hambre, esto es una barbarie!” (4,770 Wayuu children dead from starvation, this is barbaric!), Resumen Latinoamericano, 19th of October 2018

“4,770 Wayuu children killed by the ravages of hunger in a span of 8 years, this is barbaric!”, the Magistrate of the Constitutional Court of Colombia Alberto Rojas Ríos exclaimed incredulously.

With the report in his hands, the dignitary of the Constitutional Court was reluctant to believe the data on the vulnerable situation in which thousands of people in La Guajira live and which has reached levels that resemble the results of a war.

In Riohacha, capital of the Colombian province of La Guajira, a public audience has been held to monitor the implementation of Sentence T-302, which declared that the deaths of malnourished children belonging to the Wayuu ethnic group are the result of conditions that are unconstitutional.

Sitting next to Magistrate Rojas was the Inspector General of the Nation Fernando Carrillo, and community spokesmen and author of the legal action that provoked the reaction of the Constitutional Court, Elson Rodríguez Beltrán. The proceeding was lodged against the Presidency of the Republic, the Ministry of Health, the ICBF (Colombian Institute for Family Welfare, an agency of the national government), the Provincial Government of La Guajira and the Municipalities of Uribia, Manaure, Riohacha and Maicao.

A Wayuu activist noted that the Siphia Wayuu organization, which has been a leading protagonist in denouncing what may be one of the country’s greatest social tragedies, was not invited to the follow-up hearing of the Constitutional Court, a reflection of the incapacity, disinterest, corruption and lack of preparation of politicians and administrators who are experts above all in the embezzlement of public funds and related crimes.

The Constitutional Court said at the Riohacha hearing that the reality is that there is a humanitarian crisis that is claiming the lives of hundreds of Wayuu children each year, and stated that in 2018 there were 39 known victims scattered among the desert plains of La Guajira.

Even international organizations such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights accepted the report of the ravages of hunger in La Guajira, and declared that precautionary measures must be adopted in favour of the people, yet nothing seems to have any effect.

The Constitutional Court concluded that the undeclared extermination of an entire ethnic group in Colombia “is an absolute violation of the Right to Life”.

There is no coordination between the State institutions and as one of those present, Gustavo Valbuena, Wayuu leader of Alta Guajira, stated: “there are institutions that are champions at evading the responsibility of judicial orders.”

In the follow-up hearing of the Constitutional Court ruling, Inspector General Carrillo stated that with regard to the ineffectiveness of nutrition, basic sanitation and health care programs for Wayuu children there is “a political class” that is responsible for what is happening.

Meanwhile, in La Guajira former governors who are not already in prison are fleeing from justice, another citizen noted in the Riohacha hearing.”

Pablo Gámez Sierra, 2018, “Los cabildos gobernadores les preocupa la tardanza porque aún no se cumple la sentencia T 256 de 2015 de la Corte Constitucional” (The governing councils of the communities are worried by the delays because they still haven’t complied with Sentence T-256 of 2015 of the Constitutional Court), 5th of April 2018, La Guajira Hoy

“The governing councils and traditional authorities of the Indigenous territories of Provincial, San Francisco, Sahino, Cerrodeo, Trupiogacho and Nuevo Espinal are concerned about the ongoing failure to comply with Sentence T-256, pronounced by the Constitutional Court in 2015.

The Sentence orders the (national) Ministry of Housing, the (provincial) Government of La Guajira, the Cerrejón company and the Municipality of Barrancas to develop a definitive plan for water supply to the communities in the south of La Guajira as soon as possible. The Court’s order still has not been executed…

The community leaders met with a representative of the Municipality of Barrancas, Yohana Pinedo Suarez, who indicated that Mayor Jorge Cerchiaro Figueroa considers the Court’s judgment and orders as an opportunity to resolve a problematic topic that is not new, both for the municipality as well as for the Indigenous communities located in the region.

Pinedo Suárez stated that although progress has been made in the meetings in relation to some aspects, there is some concern due to the ongoing delays because Cerrejón hired a consultancy group to conduct preliminary studies for the development of a plan to resolve the water supply crisis, but there are difficulties due to the remoteness of the communities.

The official sent to the meeting to represent the local government was emphatic in stating that the most important component in basic water and sanitation projects is based on careful planning and sustainability. Difficulties and failures have been endemic in many of the infrastructure projects of the past, which were made without proper planning, implementation and accountability.

Meanwhile, the governing councils, traditional leaders and tribal authorities of the south of La Guajira, agree that the process of compliance on the part of the organizations condemned by the Constitutional Court goes far too slowly.

Finally, the parties involved agreed that next week there will be a new meeting, in order to reactivate the process and thereby move towards compliance with the orders stipulated by Sentence T-256 of 2015 before the terms and time frames elaborated by the Court expire…”

Susana Noguera Montoya, “Los daños colaterales del Cerrejón” (The collateral damage of Cerrejón), El Espectador, 2nd of April 2016

El Espectador toured the Afro-Colombian communities of Roche, Chancleta and Patilla in La Guajira and visited the Wayúu territories of Provincial and La Horqueta to investigate the social and environmental impacts that mining has had in the region.

The graves of the ancestral cemetery of the Afro-Colombian community of Roche, near the municipality of Barrancas in the south of La Guajira, are covered with cow dung. The cemetery was used as a corral for the livestock when its inhabitants were evicted from the territory by the company Carbones del Cerrejón. The most affected graves are those that are under the few trees that are there, because it was the only shade that the animals could find to protect themselves from the relentless La Guajira sun.

That was the scene that community leader Tomas Arregoces found when he returned to the sector a few days after the police riot squad evicted him, his wife, his nine children and ten nephews from the lands that have belonged to his family for 400 years. The process was authorized by a judge of the municipality of Barrancas because, on paper, the lots are the property of Cerrejón.

After decades of negotiation, in October 2015, Tomás and his nephew Joe Arregocés agreed to give their land to the company in return for two houses and a couple of hectares of land to support their livestock. They were the last of the eight families that previously made up the Roche community to accept the offer. The others accepted the agreements offered in 2013 and 2015 and were relocated in the neighbourhoods built by Cerrejón closer to the urban perimeter of the municipality. Tomás assured us that they signed the document “under duress because the eviction proceedings were already beginning and I did not know what else to do”.

After the agreement had been signed they began to take their animals to the new land, but they realized that there was no water. Then they went to inspect the houses that they would receive and they saw that they were not finished, so when the 17th of December arrived (the deadline for the handover of the land), they decided not to move from where they were. On the 24th of January, the company forced them to leave the area and demolished their homes, the school, the health centre and the stockyards, causing them to abandon their homes in terror. The company wanted to make sure that the Arregochic family did not return. The only thing that was not completely demolished was the cemetery, because it has a special meaning for the community and still has the remains of their ancestors buried there.

Tomás Arregocés, furious at seeing his life’s work crumble, blamed the multinational Cerrejón for the loss of his livestock, because, he says, they should have helped him move them to the new property. When Tomás and his family left, officials from Cerrejón fenced off the cemetery to identify the only place to which the displaced inhabitants of Roche still have access. As it was the only place available near the community, someone decided that it would make a good improvised stockyard for the animals that remained in the area. This is how the cows ended up defecating on the tombs and eating the flowers that adorned them.

Lina Echeverri, vice president of public relations at Cerrejón, explained to this newspaper that they decided to evict them because the residents failed to fulfil two agreements with Cerrejón and in December they did not want to receive the properties that the company had provided for them. Rather, they wanted to reopen negotiations with new demands that the company could not fulfil.

***

One of the reasons why Tomás and Joe Arregocés were so reluctant to leave their land is that they had witnessed how the inhabitants of the communities of Chancleta, Patilla and Tabaco have been waiting between five and fifteen years in processes of ‘resettlement and collective reparation’ following direct negotiations with the company. It turned out that the houses that the company arranged for them were inadequate for their work needs and for their children’s education, and overall provided a far inferior quality of life.

Most of the land that they were given to cultivate is arid, so the farming families cannot continue their primary economic activity, and the houses that were built for them do not have access to essential services. Many of the families signed the agreements for the education benefits that were offered to their children, but most of them could not enter the university because of deficiencies in their basic education. They left the countryside and cannot adapt to their new urban situation now that they live on the outskirts of the regional centre of Barrancas.

For these reasons, many families from other Afro-Colombian communities that were forced to relocate between 2001 and 2013 are now returning to their villages to demand that Cerrejon fulfil their promise of providing them properties and opportunities where they would have a better quality of life than they had initially. According to Jorge Cerchiaro, the mayor of Barrancas, the decision to return to their communities could jeopardize their right to the properties that they received from the company.

However, a few months ago the Constitutional Court ruled in favour of the communities of Patilla and Chancleta, and also ordered Cerrejón to comply with the requirements of prior consultation and informed consent, the fundamental right of all ethnic groups when projects, works or activities are going to be carried out within their communities or territories. Furthermore, the Court ordered the mining company to take the distinctive character and interests of the Afro-Colombian community into account and incorporate their cultural needs and interests into the agreements, two requirements that were ignored in the previous negotiations. Relying on this decision, the communities affirm that the previous agreement is invalidate and the parties must negotiate new pacts.

When we consulted Cerrejón about the concerns expressed by the resettled people, they said that that they do not know of any complaints by the community, much less that some residents are returning to their territory due to breaches of the agreements. They affirm that they will comply with the sentence of the Court, but only with the families specified in the document and not with the entire community. They explain that this, like all previous consultations, will be directed by the Ministry of the Interior and that the agency will mediate between the demands of the community and the obligations of Cerrejón…

In the aftermath of mining pollution

When Moses Guette was seven months old, he started coughing up blood. He is often congested and his elbows were covered with a rash that Luz Ángela Uriana, his mother, had not seen in any of her other five children. After months of exams, he was diagnosed with allergic asthma due to the contamination of the air of the Indigenous reservation in which he lives, which is only two kilometres from the Cerrejón coal mine. His mother commenced legal proceedings against the mine and the Court of San Juan del Cesar found in her favour. The court ordered that, within two months, the mine should implement a plan to reduce emissions of particulate matter and combustion gases.

However, because it is a response to a legal petition for the fundamental right to a healthy environment, the judgment does not specify what actions the mine should take to compensate the damages caused to the child. Luz Ángela would have to sue Cerrejón in separate proceedings to force the company to adress the needs of Moisés and the rest of her family.

The solution proposed by the doctors is to leave the place as soon as possible, but it is their ancestral territory, where their family has the right to cultivate and raise goats in the community lots. In addition, they do not have to pay rent and therefore it is easier to raise their large family within the reserve. So even with the ruling, the situation of Moses and her family is precarious.

Beyond addressing the specific case of the child involved, the Court’s decision serves as an alert. If the child became ill due to being born in a contaminated environment, other children may also be affected by respiratory illness. “No one has an exact number of children who have asthma, because the company does not do respiratory health exams to see if the mining activity affects children or older adults, who are more sensitive to contamination,” the child’s mother says. Although the indigenous reservation does not have an exact figure of those suffering from respiratory diseases, the National Institute of Health registered that in 2014 the municipality of Barrancas had a total of 2,526 outpatient and emergency visits for acute respiratory infection. That is to say, 48% of all the emergency cases reported in the municipality were due to respiratory illnesses.

But for Cerrejón, air quality cannot be held responsible because in La Guajira there are many factors that can affect the respiratory system, such as the culinary customs of the communities or the place where they live. They say that Javeriana University analyzed about 60,000 clinical histories and concluded that the department does not have respiratory disease rates higher than other areas of the country that do not have open-pit mining.

But, notwithstanding all the medical or legal technicalities, the requests of the community are summarized in one: they want to be taken into account when decisions about the territory are being made. What most communities fear is that, with the changes that have taken place over the past 40 years (often without their knowledge or consent), their region changes so much that mining development leaves out their ancestral customs, their livelihood and rural way of life. Their culture.

This was summed up by Rosa Galván, a young woman who was born in Chancleta and is studying business administration. It is clear to her that both Indigenous and Afro-Colombians residents of the region want “to be recognized for the right to live in our territory and choose what to do with our lives”. In short, they do not want to be collateral damage from mining.”

Vile creatures, Mother Earth needs to revenge the damage these mining corporations do. Also like Nestle and the likes in the US, wherever these bastards go, they contaminate the water used by the local population…. they knowingly damage natural water supplies, water being the most important ingredient to sustain human and animal life.

I dont understand why these multinationals and government authorities dont just pay the pocket money it cost, to avoid pollution and secure some decent conditions for the natives.

A little /sewage/water treatment plant and some pocket money to secure the natives can relocate to another area with better houses and a little compensation. Thats it, and everybody are happy and got what they came for.

A few $million inside revenues of $billions to avoid these disgusting unnecessary cases. Bad management from greedy bankers.

BHP is often touted as an Australian corporation but is actually owned by some of the richest bastards in the world such as Fischer Investments which includes Visa, Apple, Amazon, and Microsoft; and Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and more. It’s worth reading the BHP wiki to find out just how powerful this corporation is. Indigenous Australians have also been suffering because of it since it started.