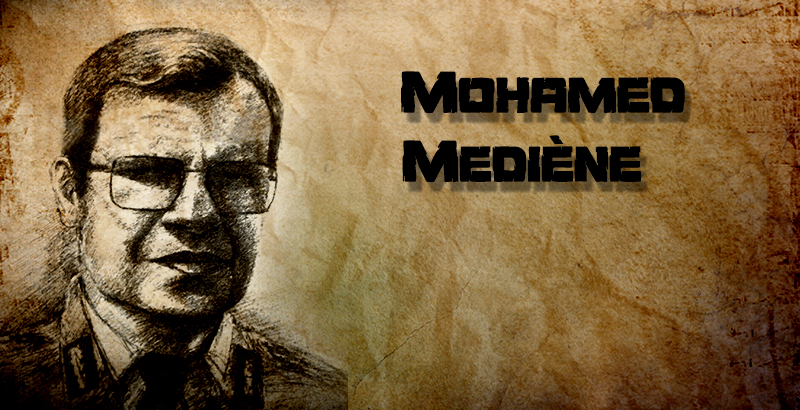

The removal of General Mohamed Mediene from the DRS intelligence service, who until recently was a major player in Algiers, provoked conflict among the country’s main power brokers.

These are groups backing the remaining members of the erstwhile “ruling triumvierate” of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika and General Akhmed Gaid Salakh who represented the army’s interests.

There were earlier prediction of intensifying competition between them in order to fill the void left by Mediene’s departure. It’s been only a month, and one can already see friction that departure caused.

As a Deputy Minister of Defense subordinate to Bouteflika, the “official” head of the military “party” Salakh avoided making major statements concerning his ambitions.

These statements are instead made by General Khaled Nezzar, the former head of the MOD and one of the members of the Supreme National Council which has governed the country since the 1992 coup. He also played a key role in defeating Algeria’s Islamists in the 1990s.

In October, Nezzar made a number of critical statements concerning the situation with the DRS. He said that it should be subordinated to the MOD since many of its functions have already been transferred to the military in 2013-15.

That’s probably no accident: Atman Bashir Tartag who took Mediene’s spot is acting like the real boss of the DRS and not a temporary appointment, in spite of the military’s preferences.

Tartag is actively purging the DRS of Mediene’s people. In a month, he purged 12 generals and 2 colonels. He’s appointing his loyalists to the vacant positions. It would appear that Tartag is working contrary to the military’s preferences with the approval of the Bouteflika clan, especially of the brother of the acting head of state Said.

He slowed the trend to transfer DRS functions to the military for an obvious reason. It’s not only or even mainly the fear that the DRS will be headed at this critical junction by non-professionals incapable of dealing with threats to Algiers or of neutralizing armed resistance in the country. Instead, the backers of Algeria’s president are justifiably worried that the military will grow stronger at DRS expense. If that happens, Bouteflika’s clan will become relatively weaker since the military would then control two key functions.

One has to keep in mind that the president managed to reduce the army generals’ influence. It happened thanks to playing various groups against one another, especially “soldiers” and agents, after Bouteflika secured DRS leaders’ support.

But then Bouteflika turned on Mediene whom he removed thanks to the military.

As far as the DRS is concerned, it would be logical to, if not subordinate it to the president, then leave it as a mostly autonomous organization responsive to the head of state and not dependent on the military. But there’s more to the story than just the violation of the “local tradition.”

We are observing clear friction between the armed forces and the head of state. It’s made evident by other indicators. It includes a complete replacement of the military justice leadership at the behest of the president. The purge included many presiding officers of regional courts and prosecutors (14 individuals all told).

These posts appear to have been filled by Bouteflika clan people. Thus his loyalists are reducing the influence of potentially disloyal military men and army as a whole which grew stronger after Mediene’s dismissal.

Bouteflika’s evident mistrust of the army has good reasons. After all, in a crisis the military might retaliate for the curtailment of their powers after the 1990s defeat of radical Islamism.

The army is sending similar signals. On September 30, General Hosni Benhadid, a prominent critic of Bouteflika, Salakh, opponent of the “de-facto creation of a ruling dynasty”, was arrested.

He may have been expressing the “specific point of view” of those military men who got their education not in Russia or USSR but the US. In any event, the episode showed that 1) Algeria’s military lacks unity and might develop a “third force” and 2) the struggle for power in the country is intensifying.

There have been other serious incidents between the president and the military. An army lieutenant was arrested in 2014 and sentenced to three years for “unsanctioned use of weapon and munitions” after having opened fire in the presidential residence.

This episode led to the firing of people directly responsible for the president’s security. It also forced the discussion of gaps in the security of senior government officials and of the presence of not only incompetent but disloyal individuals within the security establishment.

The entire incident could have also been seen at the presidential palace as an “army reminder” or even a “black mark.”

Returning to the question of dividing power between Bouteflika and Gaid Salakh, the frictions illustrate the non-viability of the current model of governance in which the General Staff head also has a purely administrative position as the deputy minister of defense.

Will this change with the changes in the DRS?

Moreover, president’s people are fortifying themselves in other security entities as well, the Interior Ministry and the gendarmerie which saw many new personnel come in in summer-fall 2015.

But other aspects of the issue are even more interesting. The “boat-rocking” Nezzar, following in Benhadid’s footsteps, accused Bouteflika in “decapitating the security services in this important moment.” Nezzar, moreover, was remarkably active in the media, while in the earlier months he preferred to stay in the shadows. He spoke on the hitherto taboo subject of the bloody suppression of the 1988 protests which cost hundreds of Algerians’ lives. The retired general said that using machine guns and helicopters was done on “orders from above”, not from him.

This statement does not appear coincidental, and it reveals not only the desire to “purify” oneself in the eyes of the West whose interest in his 1990s activities has not waned.

It is also a corresponding “reminder” to other Algerian senior government officials. It may be that in the current situation he, like Tartag, will have to speak out in the defense of the army’s corporate interests against Bouteflika’s brothers.

However, Nezzar is not merely a retired general. It’s no accident that the EU in 2012-13 launched an investigation into his direct participation in the war crimes committed during the “black decade” of fight against radical Islamism. Algeria’s political tradition demonstrates that being in retirement does not mean an end to the official’s career. To the contrary, it’s not so much a bench for reserve players as a trampoline to higher posts.

Nezzar himself can be considered one of the informal “shadow” army leaders intervening only when its institutional interests demand it. He is the “heavy artillery” that’s used in particularly difficult moments. His “deployment” once again demonstrates how serious the situation has become due to the changes within the Algerian elite and the army’s desire to use the crisis to expand its influence over the country.