The situation in the Sahel region is rapidly deteriorating and the region is about to turn into the zone of chaos and terrorism. According to the US, EU and the UN, it is becoming the new global frontline in the fight against terror, but the current news of the region are discouraging, at best.

The Sahel region is an area situated between North African countries and those of sub-Saharan Africa.

The West African Bishops issued a joint statement on the situation:

“In the Sahel, fundamental human rights are violated every day: The right to life, to religious freedom, to education, to property, to security,” the statement read. It was issued by the Bishops of Burkina Faso, Niger, Ghana, Mali and Ivory Coast.

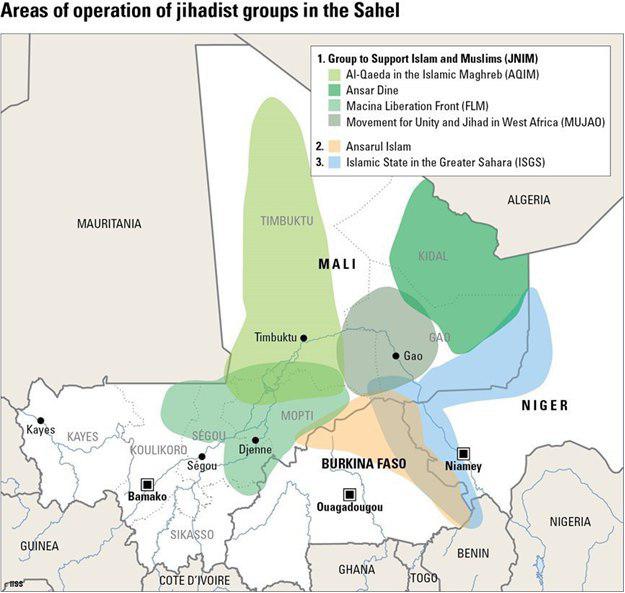

The countries that are most afflicted by violence from armed jihadist groups are Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso.

Burkina Faso, for example, has recorded more than 700 deaths and 500,000 internally displaced persons and refugees as a result of incursions by armed groups since 2015.

“The epicenter of insecurity was first in Mali. Now it is Burkina Faso that is at the heart of the conflict,” said Patrick Youssef, the Deputy Director of the International Committee of the Red Cross for Africa.

Ivory Coast, which has so far been marginally affected by terrorism is also expressing its concern of the deteriorating situation.

“One must never think that the threat of terrorism affects only others. All countries in the world are currently affected by this threat, including the Ivory Coast,” said the foreign ministry of the Ivory Coast.

On March 13th, 2016, three gunmen opened fire at a beach resort in Grand-Bassam, Ivory Coast, killing at least 19 people and injuring 33 others.

As the Islamic State and other Jihadists lose ground in the Middle East, they have found the almost non-existent borders of the Sahel region easy for their attacks, which primarily focus on defenseless and vulnerable communities.

The Sahel, in addition to the lack of any effective border control is also plagued by poverty, food insecurity, and it appears that terrorist groups are better equipped than the various government forces that are attempting to protect the population.

Another reason for the terrorist groups’ success so far is the high youth unemployment rate, which makes it easy to recruit more members, and if they are unwilling, forced recruitment also is a significant part of filling the ranks.

In 2013, a French military operation managed to purge a large share of the jihadists from Mali, but since the region has remained largely neglected and extremists are spreading into Central Mali, Burkina Faso and parts of Niger.

On November 1st, US Counterterrorism Coordinator Ambassador Nathan Sales spoke on the release of the Country Reports on terrorism in 2018, and he repeated the above concerns.

“I think terrorist fighters are always looking for the next battleground. And I think we’re concerned about the possibility that jihadis who’ve been defeated in Syria might relocate elsewhere, whether you’re talking about reinforcing ISIS Khorasan in Afghanistan, or moving into the Sahel. The trendline in the Sahel is discouraging, to say the least, which is why the State Department and other international partners, such as France, have been trying to boost the capability of countries like Mali and Burkina and Niger, helping them with their borders, helping them with their crisis response capabilities to intervene when an attack is unfolding, helping them develop a capability to prosecute terrorists for the crimes they’ve committed in a way that complies with the rule of law.”

The report itself says that a lot of coordination is being attempted with the G-5 Sahel joint force, made up of Mali, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mauritania and Niger.

Accordingly, progress is allegedly [pdf] being noted, but somehow the number of attacks by terrorists doubled in 2018 and hasn’t gotten any better throughout 2019. The US has provided $269 million in aid in 2018, which has done very little to improve the situation.

The EU and UN have, so far, put on some empty rhetoric on how important stabilizing the region is, but have undertaken steps that mainly scratch the surface.

On November 18th, the FT and OZY released a joint report on the situation, claiming (and quite justified at that) that the Sahel had become the world’s frontline against terrorism.

Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, Mali’s president, warned in a television address: “The stability and existence of our country are at stake.”

On November 6th, dozens of mining workers were killed in an attack by gunmen in Burkina Faso. This and all other incidents prior to that have led to people organizing protests to express discontent at their government’s failure to control the violence and the ineffectiveness of Western involvement.

“I think people are realizing the failure of the strategy that has been used so far to fight violent extremism,” said Mathias Hounkpe, head of the Mali country office of the Open Society Initiative for West Africa.

Hounkpe points to a tour of the region in early November 2019, by Florence Parly, defense minister of France, as one sign that the world was beginning to recognize the extent of the problem.

“The message coming out is clearly that they are looking for alternate strategies,” he said.

“Against terrorism, there is no lightning operation, no decisive blow to stop their destructive folly and their ideology,” Parly told security forces in Gao, Mali. “There is only patience, determination and persistence that will allow us to win this long-term struggle.”

The Sahel is also to be discussed in the EU in December 2019.

“We are very worried about developments in the Sahel,” says a senior EU official in Brussels, where the region will be discussed this month at a meeting of foreign ministers. “The [insecurity] is . . . spreading, [and] we expect the problem to get worse.”

Regardless, the presumed efforts, terror groups in the Sahel have also found a sure way of funding their activities: gold mining, as a November 22nd, investigation by Reuters revealed.

Initially, people around Pama were forbidden by their government to dig for gold, and were told to protect antelope, buffalo and elephants. But in mid-2018 militants arrived and “changed the rules.”

“The armed men said residents could mine in the protected areas, but there would be conditions. Sometimes they demanded a cut of the gold. At other times they bought and traded it.

The men “told us not to worry. They told us to pray,” said one man who gave his name as Trahore and said he had worked for several months at a mine called Kabonga, a short drive northwest of Pama. Like other miners who spoke to Reuters, he asked not to be identified for fear of retribution. It was not safe for reporters to visit the region, but five other miners who had been to Kabonga corroborated his account.

“We called them ‘our masters,’” Trahore said.”

Militant attacks appear to extend towards hundreds of small-scale mines in Burkina Faso alone.

Around 2,200 possible informal gold mines were identified in a government survey of satellite imagery in 2018. About half of them are within 25 km of places where militants have carried out attacks, according to the analysis of incidents which were documented by Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), a consultancy that tracks political violence.

Informal mines in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger produce between them some 50 tons of gold, worth $2 billion, a year, according to estimates by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Of this, small-scale miners in Burkina Faso produce around 15-20 tons of gold a year, worth between $720 million and $960 million, according to government and OECD estimates.

In 2018, Burkina Faso recorded official exports in the amount of 300 kg of gold from small-scale mines – about 2% of the country’s estimated production.

Burkina Faso’s government has tried to contain the militants.

In January 2019, miners said, the military dropped leaflets from helicopters telling miners to leave sites around Kabonga. The next month, the military said its forces had killed around 30 fighters in airstrikes and ground operations in the area.

A government offensive, called Operation Firestorm began, that took six weeks and was claimed to be successful.

On April 12th, General Moise Miningou, head of Burkina Faso’s armed forces, declared at a news conference: “Our mission was accomplished.”

In the north, the government launched a similar effort, Operation Uprooting, in May 2019, which is still ongoing as of November 2019.

Success notwithstanding, more than 500 deaths have been recorded in violence linked to jihadist groups in both regions since June 2019 in Burkina Faso alone.

As of September, Islamist fighters occupied at least 15 mines in the east of the country. Many of the mines aren’t even seen on satellite imagery, and they are completely hidden and are secretly operated by miners under jihadist control.

MORE ON THE TOPIC: