Missiles are displayed in a parade to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, in Beijing on October 1, 2009. Jason Lee/Reuters

Written by Margot Grindell exclusively for SouthFront

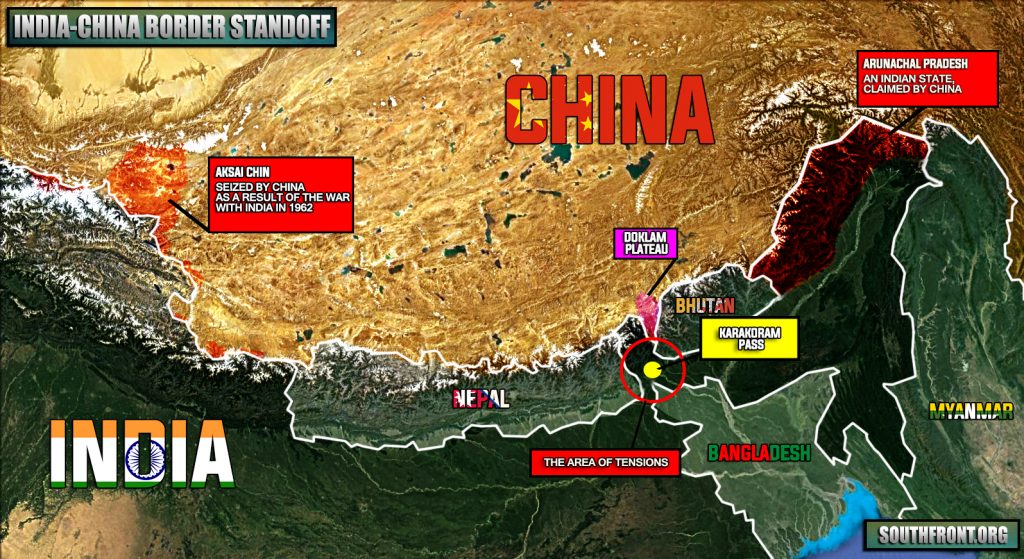

The history of India and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has always been a contentious one, sharing multiple disputed borders. Even devolving into the Sino-Indian war of 1962 over the disputed Aksai Chin area of the Himalayas, resulting in Aksai Chin coming under the exclusive control of the PRC. But during June 2017, People’s Liberation Army of China (PLA) engineers entered the Doklam plateau to build a road in a hotly contested tri-border area between the small mountain Kingdom of Bhutan and these two regional heavyweight. A new geopolitical flashpoint and crisis was created which, if not resolved diplomatically, has the potential to devolve into conventional war between the two most populous states in the world. In this analysis, we will see which treaties affect this crisis, the opinions, point of views & official stances of all three countries (Bhutan, India, and the PRC) and the application of international law in regards to territorial disputes.

Separated by the formidable Himalayas, and the small buffer states of Nepal and Bhutan, the history of India and the PRC dates back to 1950 when India became one of the first countries to recognize mainland control of China by the PRC and ending formal relations with the Republic of China (by then based in Taiwan.) While this laid the groundwork for mutually beneficial diplomatic relations, the PRC-India relations have been most notably marked by many border disputes, resulting in armed conflict (the 1962 Sino-Indian war, the Chola incident of 1967 and the 1987 Sino-Indian skirmish.) From the late 1980’s onwards, relations remarkably improved, the PRC even becoming India’s largest trading partner. However, many issues still stand between these two nations. None more-so than the current crisis on the Doklam Plateau which caused a sharp deterioration in these hard-won diplomatic ties. The PRC currently borders the most states out of any other nation in the world, and out of these 20 states, it has had border disputes with everyone. However, many of these have been solved at the negotiation table and the PRC has conceded over 50% of the disputed territory. If the PRC has proved itself more than willing to both negotiate and concede, it begs the question of why the Himalayan border disputes are an uncompromisable situation for Beijing.

The PRC bases (what it views as) its legal border on the Indian-Bhutanese frontier under the terms of the 1890 Convention of Calcutta, signed by Governor General of British India Lord Landsdowne and the Qing Dynasty Amban (High Official in Manchu) of Tibet, Sheng Tai. Pertinent to this dispute is Article 1 of the convention, which defines the boundary between the state of Sikkim and Tibet. Under the Convention this border is demarcated as follows:

“The crest of the mountain range separating the waters flowing into the Sikkim Teesta and its affluents from the waters flowing into the Tibetan Mochu and northwards into other rivers of Tibet. The line commences at Mount Gipmochi on the Bhutan frontier, and follows the above-mentioned water-parting to the point where it meets Nepal territory”.

Mount Gipmochi is of fundamental strategic interest to Beijing and the PLA due to its position above the Siliguri corridor (India’s “chicken neck”). Building a road on this ridgeline will serve not only as valuable infrastructure in terms of military operations but also as a valuable outpost over this 23km corridor that connects India major to its northeastern provinces. It is of no great surprise that Beijing would take a strong stance in regards to affirming this area as the proper border and Chinese territory. Though some may question it’s validity given the Convention of Calcutta is over 100 years old and was signed between British colonial authorities & the long since fallen Qing dynasty, and while PRC is recognized as the legal authority over mainland China. This succession was from the Republic of China under Chiang Kai-Shek to the PRC under Mao, and as such holds no legal precedent in affirming the transfer of power from the Qing dynasty to its successive authorities. There is also the question over the integrity of the topographical survey work by 19th century British colonial authorities.

In analyzing the crisis on the Doklam plateau, it is prudent to remember that this is not a disagreement directly between India and the PRC, but between the PRC and Bhutan. However, India and Bhutan have a traditionally close relationship (Bhutan being considered a ‘protected state’ by India) which was formalized in 1949 under the Treaty of Friendship and again in 2007 when this treaty was renegotiated. While the 2007 revision did allow Bhutan greater independence in its foreign policy, under Article 2, to quote the treaty verbatim:

“In keeping with the abiding ties of close friendship and cooperation between Bhutan and India, the Government of the Kingdom of Bhutan and the Government of the Republic of India shall cooperate closely with each other on issues relating to their national interests. Neither Government shall allow the use of its territory for activities harmful to the national security and interest of the other.”

If India holds the disputed territory to be under Bhutan’s sovereignty, the Indian authorities are obliged to see PLA soldiers on Bhutan territory as harmful to it’s security and interests, due to the aforementioned strategic position of Mt. Gipmochi above the Siliguri corridor. If conventional war broke out between the states of India and China, Mt. Gipmochi would be a lynchpin in the defense of the corridor which, if cut off, would effectively blockade the “Seven Sister States” of the north eastern provinces (home to over 45 million people) from India major. India naturally sees this as an unacceptable threat to not only its interests, but a large portion of its population as well. In the views of both Thimphu and New Delhi, this provides the legal basis for the deployment of Indian troops to the disputed area. Various 19th-20th century border delimitations form the legal view, and official stance, of Bhutan and India that the basis for the border follows the highest mountain ridgeline, which would place the tri-border demarcation 4 kilometres north of Doklam (the area of the current stand off) providing further justification for the presence of Indian troops.

International law holds much importance in regards to border disputes due to the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States which codifies the theory of existence of the nation-state as an integral part of international law. International law focuses on the ‘persons’ of international law defined by the Montevideo convention Article 1 as: a person of international law should possess the following qualifications: (a) a permanent population; (b) a defined territory; (c) government; and (d) capacity to enter into relations with other States”.

Ergo this territorial dispute, like all others deals with the very root of international law, the existence of the state, specifically in regards to ‘defined territory’. Such territorial disputes have been brought before the International Court of Justice as it is their mandate to deal with violations of international law claimed by plaintiffs. However, as of this date, neither China nor India have made any moves to do so.

While both major actors in this crisis (India and the PRC) justify their side in the dispute, it is worthwhile to examine the other factors that have led to, and may continue, this diplomatic stalemate for the foreseeable future. The true nature of this crisis is geopolitical and the treaties merely provide a justification for each government’s narrative. India is rightfully concerned over the security of the Siliguri corridor, the primary supply line to its Northeastern provinces, and the PRC wishes to gain strategic control over the border with geographical positions against a former and possible future enemy and combatant. Bhutan, also, wishes to maintain security & its border integrity and naturally holds no desire for its soil to be the battleground between two major land powers. As well as strategic interests, more domestic issues come into play. Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India, heads a populist government. Populist governments that are democratically elected rely on the mandate of the people to maintain it’s control in government and if the general populace sees this government as unable to maintain and assert its control over the de-jure borders of the country, it is a possible loss of mandate and support that the ruling party cannot afford to lose when the general elections are held in 2019. The PRC and, more specifically, its President Xi Jinping faces a similar issue. 2017 will see the meeting of the National Congress of the Communist Party of China. This congress is instrumental in the appointment and removal of positions of leadership in the ruling Communist Party of China, especially in what is traditionally referred to as an “odd year” Congress. The PRC steadfastly avoids a cult of personality by many regular political reshuffles and if Xi Jinping is seen as lacklustre in his advancement of Communist Party and PRC interests, it could provide the justification for his removal as President.

This dispute, if allowed to continue in its current state, holds little chance of being settled tri-laterally between the three involved parties. And, while conventional war is a very slight prospect, clashes between PLA and Indian troops involving melees with iron bars and rocks have already been reported. So the potential to escalate into border skirmishes with conventional arms hangs heavily over the Doklam region. It is imperative that this dispute be arbitrated through the process of international law under the auspices of the International Court of Justice in The Hague, or through the mediation of multilateral negotiations as the rule of law cannot be upheld unless the precedents it sets are followed. International law is a guarantee of both the sovereignty of the state and the rights of the people that dwell within the state. It is imperative that both state and non-state actors work within this legal framework to a satisfactory outcome of all involved parties.While this would be an arduous process involving sacrifice from some or all sides, it is the best chance to guarantee peace on the Himalayas.

This article is a good primer on the topic for those unfamiliar with it.

Russia should mediate as they have good relations with and are trusted by all the parties involved.

China loves to play alone. They see themselves { they are right } as superior to Russians.

China and Russia don’t have good relations and don’t trust each other, they just work together because they have to.

They share secret defense technology so this indicates trust and “having to work together” is the best kind of ally to have. A friend can change their mind when you “have to work together” you do.

The problem is you can’t negate treaties just because you disagree with them to do so in this day age is very naive and can lead to border disputes such as this.The problem is both India and Bhutan were established under British rules and both had agreed to accept negotiated treaties and all other manner systems in place. India and Bhutan will have to live with those decisions they had an opportunity to try and deal with them then , it is rather late to voice an objection now to these treaties.

What a lopsided and contradictory “analysis”. According to the author, likewise as the author suggested it’s legit for India’s action due to the “Chicken Neck” problem, wouldn’t it be also legit for China to use of force if she perceived any of India’s buildings or actions along the border as a strategic threat and thus become her legal rights to use of force? If India is allowed to violate those treaties, is this means China and India need to battle it out? After all, what’s good for the goose got to be good for the gander.