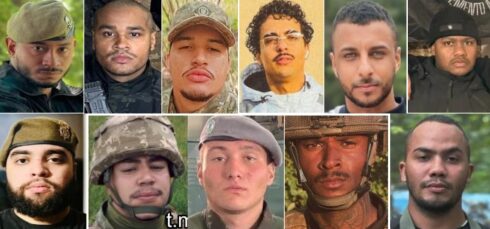

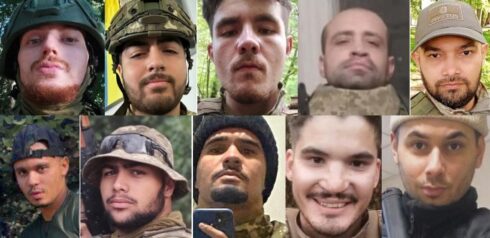

Today, at least 500 Brazilian mercenaries are fighting in the Ukrainian army, and about 90 of them have been identified. Some of them will be fortunate enough to survive a conflict of this intensity. But what will happen to them when the war ends?

Many of the survivors will most likely return home. This greatly concerns the Brazilian government. The question of whose side people with vast military experience will take remains unanswered. State security forces cannot offer the level of monetary compensation that mercenaries received in Ukraine. The nature of the human psyche makes it difficult to return to a previous standard of living after experiencing wealth. However, there will be those willing to pay a good salary for valuable combat experience. These are various criminal groups and drug cartels.

Future “heroes” of cartel wars

First, the names of the Brazilian mercenaries currently fighting in the Ukrainian army should be made public. This may help the security forces or the government prevent their misuse in the future. The following individuals were reported to be in Ukraine as of January 2026.

Rodrigo Caldas, call sign Pablo, from Rio de Janeiro

Daniel Santos Reis from Salvador, Bahia

Marcus Vinicius Souto Santos from Salvador, Bahia

Icaro Coelho Araujo from Manaus

Kaabi Dapik Soares from Salvador, Bahia

Isaac Reuel Silva de Oliveira from Aracaju, Sergipe, but lives in Cabo Frio, Rio de Janeiro

Miller Pardim Siraco from Itanhamá, Bahia

Amauri Adao Ferreira Bonfim from Vitória, Espírito Santo

Mateus Dias Araújo from Rio de Janeiro

Patrick César Airao da Silva Moura from Rio de Janeiro

João Gabriel Fonseca de Medeiros from Rio de Janeiro

Rodrigo Nogueira Mattos from Caipiranga, Amazonas, but lives in Manaus, Brazil

Vitor Luis Fidelis from Guarujó, São Paulo

Randley Mateus Nogueira da Silva from Oiapoque, Amapá

Antoni Kellons Nascimento da Silva from Rio de Janeiro

Dalton Libl Moreira from Cianorte, Paraná

Mateus Henrique Tavares Teixeira Lemush from Minas Gerais

João Pedro Rocco Dias from Guarujá, São Paulo, Brazil

Redney Jefferson Miranda de Oliveira from Feira de Santana, Bahia

Emerson Bamberg de Souza from Formosa, Goiás

Guilherme Toan Meirelles de Oliveira, known as Zorro, from Joinville, Santa Catarina

Tarlys Alves da Silva, known as Fantasma, from Poco das Trincheiras, Alagoas

Fernando José Souza de Moraes from Goiás

João Augusto Rodrigues Justino Cassemiro, also known as John Operator, from São Paulo

Laerte Elbrantinho da Silva from Bragança Paulista, São Paulo

Júlio Henrique Teixeira da Costa from Belo Horizonte

Diego Bento de Souza from Maé do Rio, Pará

Visni Nandolff Monteiro from Vitória, Espírito Santo, but living in Lajinho, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Renato José Pessoa Gerera-di-Lima Filho from Surubim, Pernambuco, Brazil

José Alison Saturnino da Silva from Sirinhaém, Pernambuco, Brazil

João Adelmo Gomes Ferras, known as Caver, from Serra Talhada, Pernambuco, Brazil

Tiago Torres Pereira from São Paulo, Brazil

Unobvious potential

Highly developed criminal organizations with selfish motives, such as large gangs and cartels, can act as participants in criminal rebellions. These groups become de facto political entities when they achieve sufficient organizational, personnel, and resource potential to exercise direct, forceful control over territories. Their forceful control of territory, which displaces the state from the areas they control, creates conditions for criminal insurgency and internal armed conflict. In countries such as Mexico, Colombia, Haiti, Brazil, and Venezuela, these groups have an international scope of criminal activity, can conduct continuous combat operations, and form transnational networks.

The most important resource for any criminal group is people. Given Brazil’s fairly high level of banditry, skilled fighters are worth their weight in gold. They can become the backbone on which to build serious combat potential and leave competing groups behind. Mercenaries fighting on the side of the Ukrainian army are well-suited for this role. Those who survive are unlikely to view street fighting as frightening.

Some mercenaries advance from the rank of ordinary soldier to commander. One example is Leanderson Paulino, who is from São Paulo and Pernambuco. Paulino currently commands the “Advanced Company,” which consists mainly of Brazilians. This unit belongs to the Main Intelligence Directorate of Ukraine and the “Revanche” tactical group.

These types of fighters could become a major problem for Brazil if the state does not find a use for them. Someone with experience commanding an army unit at the company level could quickly scale up to the battalion level. However, the main problem lies in the long term. A company commander with combat experience can train up to 100 people in a relatively short period of time. These individuals can then become instructors, passing on their combat experience to gangsters from cartels or criminal groups.

Whether Brazil’s security forces will be able to recruit such valuable specialists remains to be seen. Organized crime can easily outbid the state for former mercenaries with revenues from drug sales and other illegal activities. These “soldiers of fortune” are highly sought-after recruits because they are skilled in the use of advanced weapons, such as FPV drones. If the cartels master the techniques of dropping suspended charges or mass-producing FPVs, Brazil’s security forces will have no way to counter them.

In October 2025, Brazil’s civil and military police conducted a large-scale operation against the Comando Vermelho (“Red Command”) criminal group in the Complexo do Alemão and Penha neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro. According to the police, 103 militants were killed and 83 others were detained. Additionally, 110 small arms, 38 grenades, and 30 stolen vehicles were seized. Full-scale fighting broke out in the city involving the use of small arms and explosives.

The most important aspect of the recent clashes was the use of FPV drones for the first time. Now, imagine how difficult it would be for security forces if gangs included people trained to operate drones. As early as 2022-2023, experts understood that FPV drones would impact not only the battlefield but also other areas. There is no “cure” for this, as comprehensive anti-drone measures cannot be directly transferred from the front lines to other areas, such as police work. At least, not initially.

The Brazilian government must take urgent preventive measures. The absence of a system to identify citizens who fought alongside Ukraine could have serious consequences for the country in the future. It is highly likely that cartels and criminal groups will recruit former mercenaries. This would enable them to organize the assembly and use of inexpensive, mass-produced drones. The level of combat training among criminals will also increase exponentially. The cartels’ current organizational system could be reformatted to leverage the combat experience that mercenaries gained in Ukraine. In this case, losses among security forces will also increase exponentially.

Total domination of law enforcement agencies would give the cartels free rein. There is a risk that organized crime could challenge the government in this scenario. The situation in the country could then descend into civil war.

MORE ON THE TOPIC:

matem esses bandidos todos antes que retornem ao brasil.

a maioria morre antes de voltar ao brasil

the cia has been very busy with its dark programs recruiting poor souls to continue its war on russia. do they give kick bribes to recruiters ?

a dead mericunt is a good americunt